Opening Up a Chinese Miracle

This year marks the 40th anniversary of China’s reform and opening up. Just as Chinese President Xi Jinping pointed out in the report delivered at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC), Chinese people today are closer, more confident, and more capable than ever before of making national rejuvenation a reality. The major reasoning for President Xi’s statement is China’s achievements over the past 40 years.

In 1978, China’s per capita GDP stood at only US$155, and more than 80 percent of its population lived in rural areas. At that time, China’s imports and exports accounted for only 9.7 percent of the country’s total GDP. Essentially, 90 percent of the country’s GDP was not related to the international economy. However, over the 40 years since China’s historic reform and opening up, the country’s GDP has averaged an annual growth rate of around 9.5 percent in comparable prices. In human history, never has a country with such a huge population and weak foundation been able to realize such a high-speed and long-term growth. It is more than appropriate to call China’s progress over the last 40 years a “China miracle.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, almost all developing countries, socialist countries included, carried out reform and opening up. However, instead of prosperity, these reforms caused economic collapse, stagnation and crises in most places. Some economists dubbed the 1980s and 1990s the “lost 20 years” for developing countries. However, in the same international circumstances, how was China able to realize consistent high-speed economic growth?

The rapid growth has primarily been attributed to China’s “latecomer’s advantage” and flexible developmental mentality enabling the country to adapt to changing situations. A country’s economic growth mainly depends on technological innovation and industrial upgrading. Technological innovation involves the introduction of technologies that improve on current technologies, and industrial upgrading refers to greater added value in a certain industry. Thus, technological innovation and industrial upgrading can be achieved by imitation, importing or integration of existing and mature technologies and industries from other countries. This avenue was dubbed the “latecomer’s advantage” in economics. When its economic foundation was weak, China capitalized on its latecomer’s advantage to achieve faster economic growth than developed countries.

Due to a contrasting developmental mentality, China’s economic performance was totally different from other countries during the transition. Back in the 1980s and 1990s, the popular idea then was that since the market economy was superior to the planned economy, all countries’ reforms should point towards a market economy. This trend advocated shock therapy to promote immediate trade liberalization, large-scale privatization and marketization within a country coupled with sudden release of governmental control and withdrawal of state subsidies and protections.

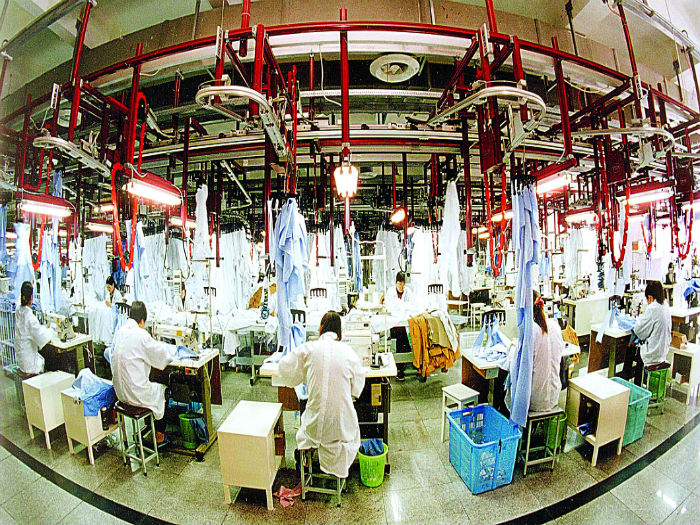

This practice totally overlooked a large group of capital-intensive state-owned enterprises of great scale. Overnight reform removed almost all protections and subsidies fueling these enterprises, which forced them to shut down immediately, leaving a great number of people out of a job and creating social instability. During its 40 years of reform and opening up, China has placed great importance on emancipating the mind, seeking truth from facts and “crossing the river by feeling for stones,” which calls for prudence and pragmatism in navigating forward in unfamiliar territory. Large state-owned enterprises were given necessary protections during China’s transition period. At the same time, market access for China’s labor-intensive processing industry which had advantages over many countries opened. Optimizing the available circumstances, China’s labor-intensive processing industry embraced development at a breakneck speed. Rapid development amassed capital which gradually transformed China from a capital-scarce country to a capital-rich one. Many industries in China which previously lacked comparative advantages became competitive quickly. Enterprises improved their viability by leaps and bounds. Due to these changes, the Third Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee held in 2013 made the decision to comprehensively deepen reform and pointed out that China must deepen economic system reform by focusing on the decisive role of the market in allocating resources.

Looking back across the 40 years, experience that will enhance China’s future development is providing guidance. First, to realize high-quality development, comparative advantages must be optimized to create competitive advantages. China is now a middle-income country. Its per capita GDP at market exchange rates is around US$8,100, compared to the United States’ figure of around US$57,000. The big gap illustrates China’s comparatively backward labor productivity compared to developed countries, and China is still sitting on abundant latecomer’s advantages yet to be explored. Second, China should continue to emancipate the mind and seek truth from facts. As the largest developing country in transition on the planet, China must steadfastly promote the emancipation of mind and the value of truth. It should keep innovating in practice rather than simply copying experiences or theories from developed countries.

If China can achieve both of the two points as mentioned above, its economic development can improve in quality while maintaining a relatively high speed. By 2035, the country will basically realize socialist modernization, and by the middle of this century, China will become a great modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious and beautiful. National rejuvenation is a dream for all Chinese people. And presumably every developing country has the dream of becoming a modern, industrialized and high-income country. Compared to developed countries, China’s experience and theory carry more referential significance for other developing countries.

Justin Yifu Lin is a renowned economist, honorary dean of the National School of Development and dean of the Institute of South-South Cooperation and Development at Peking University.

Source: China Pictorial

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +