Will US-Iran Crisis Declare Nuclear Deal Dead?

As the dust settles on this most recent and severe crisis between the US and Iran, it appears that for now there is still life in the Iran nuclear deal, but it is hanging by a thread.

The fallout of the United States killing of Iranian Qassem Soleimani, the high-profile commander of the Quds Force of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, continues to reverberate around the Middle East.

Tensions between Iran, Iraq and the US have dramatically escalated since his death last Friday, with the Iraqi Parliament calling for the expulsion of all US and foreign troops from its territory, and the Iranian parliament passing a bill to designate US forces as “terrorists”. In the early hours of morning on January 8, events further intensified as Iran launched its first retaliatory strikes against the US, bombing two airbases housing US troops in Iraq with ballistic missiles, according to the US Department of Defence.

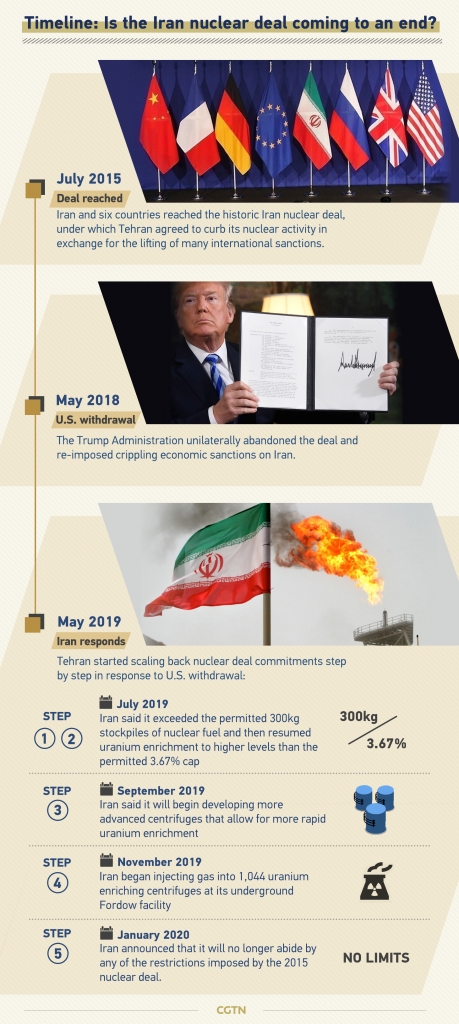

The fallout of Soleimani’s killing has also spilled over to the Iran Nuclear Deal, the agreement signed in 2015 by Iran and the five permanent members of the Security Council, Germany and the EU. Speaking on January 5, the Iranian government announced it no longer intends to abide by any restrictions to its nuclear program, sparking fresh doubts as to whether the fledgling deal, already on life support after the US unilaterally left in 2018, is finally dead and buried.

Is the deal dead?

On the surface, the latest roll-back appears to have all-but “finished” the deal. According to Sunday’s announcement, Iran will now have “no limitations in production including enrichment capacity and percentage and number of enriched uranium and research and expansion” with regards to its nuclear ambitions.

Tehran is now effectively able to set its own enrichment capacity—already at a greater than agreed level of 3.67 percent—severely increasing its potential for creating nuclear weapons. “If there’s no limitation on production, then there is no deal”, David Albright, president of the Institute for Science and International and Security, said, arguing that speculation should now turn to how quickly Iran can enrich its uranium to the levels required for making warheads.

There also appears little appetite from Washington to re-join the JCPA, or abandon its “maximum pressure” policy of crippling sanctions on Iran’s oil and financial sectors, especially in light of the latest attack. Far from doubling back, US President Donald Trump spent the initial days following Soleimani’s death talking-up further action against the country by identifying 52 targets within Iran that the US will hit “very fast and very hard”, and sending an extra 4500 troops to the region.

But for all the talk of abandonment, Iran’s announcement does crucially offer a lifeline—albeit thin. The latest statement does not include a formal declaration to leave the nuclear deal, nor that the roll-backs are permanent. Iranian foreign minister Mohamed Javid Zarif tweeted that the latest move, as with the previous four roll backs, are “reversable”, on condition that economic sanctions by the US are lifted or if it starts to see the economic benefits it was promised as part of the original deal.

It has also stated that the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) will continue their unrestricted visits to Iranian nuclear sites, keeping open a vital avenue for the wider world to monitor the country’s nuclear actions. The IAEA have in general praised Iran’s execution of the deal, claiming in April last year that it had been “implementing its nuclear commitments”, despite the US’s withdrawal.

Just as importantly, Iran has also not announced aggressive plans to start enriching uranium at a level of 20 percent—the second step in making weapons-great-plutonium—instead continuing at present levels. Eric Brewer, a former official at the US National Security Council says this is something Iran could have done if it wanted to do something more “aggressive” in light of Soleimani’s death.

Other signatories must do more

Iran’s actions have also crucially not dissuaded other participants to the deal from striving to save it. China has promised to make “tireless efforts” to ensure the deal remains, while on Wednesday, the new EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen vowed that the EU “will spare no efforts” in ensuring the deal remains alive.

Given the door has been left open by the smallest of cracks, it is now up to them, along with Russia, the UK, France and Germany, to find a way of easing Tehran’s security and economic woes so the reversing of its roll-backs can begin.

In this regard there has been some success. China and Russia’s recent four-day navel exercise in the Gulf of Oman with Iran has helped satisfy some of the security concerns harvested by an isolated Iran, and acted to counterweight Washington’s overbearing presence in the region. At the same time, France has attempted to boost Iran’s economy with a direct US$15 billion credit line plan for the country, although it hinges on whether Washington will block it or not.

The latter—reviving Iran’s economy—appears to be the priority for the government in Tehran, with foreign minister Zarif hoping its latest roll-backs will act as a “wake-up call” and cause the remaining six signatories to trade more with it. This puts a greater impetuous on the European parties to find ways around America’s sanctions, something that so far has proved difficult. Efforts to build a system that insulates European firms from these sanctions, enabling them to buy Iranian oil and goods, has failed to yield any significant results, and European oil refiners are still refusing to buy more Iranian oil, in fear of repercussions from the US Treasury.

As all six continue to search for ways of bringing Iran back to the table, “restraint” has been called by China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi, given “military means will lead nowhere” and that “maximum pressure won’t work either”.

New strikes intensify tensions

Whether all sides can show the kind of restraint the Chinese foreign minister has mentioned, remains to be seen. Iran’s latest strikes against two airbases in Irbil and Al Asad fly in the face of that, although according to Wang Jin, an associate researcher at the China Institute of Contemporary International Relations, they were expected.

Speaking before the latest strikes, Wang predicted Iran might retaliate through “military exercises [and] missile tests”, but that US military officials would have been aware of this.

Iran has justified the strikes as a “proportionate measures in self-defence” but has also said that it sees them as an end to their quest for revenge, and that it does “not seek escalation or war”, according to a tweeted statement by foreign minister Zarif.

That statement, coupled with no loss of life to American and Iraqi troops, appears to have been enough to appease the Americans in the short-term. President Trump, unusually quiet as news came through of the strikes, spoke on January 8 to back away from further military confrontation, noting Iran “appears to be standing down, which is good for all parties concerned and a very good thing for the world.”

While narrowly moving the US away from the brink of war, Trump did promise further economic sanctions as a response to the strikes, although given his “maximum pressure” policy is already at full throttle, experts are unsure of where those extra sanctions can come from.

In the context of the Iran nuclear deal however, the president was less cagey. Speaking directly to the remaining signatories, Trump called on them to quit the deal, and vowed Iran would never be allowed to obtain nuclear weapons.

“The time has come for the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Russia and China to recognize this reality,” Trump said. “They must now break away from the remnants of the Iran deal or JCPOA. And we must all work together toward making a deal with Iran, that makes the world a safer and more peaceful place.”

All will refuse Trump’s demands given their unanimous belief in the agreement, but it does sadly highlight how unlikely the Americans are to return to a deal they once so proudly championed.

Despite this, as the dust settles on this most recent and severe crisis between the US and Iran, it appears that for now there is still life in the Iran nuclear deal, but it is hanging by a thread.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +