Gathering Strength for the Future

There are issues that concern everybody, like climate change, the need for sustainability, and such major public health issues as the COVID-19 pandemic, on which our two countries need to work together on good terms.

In his recent speech, delivered at the Mansion House in the City of London, Britain’s latest Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said that the “golden era” between the United Kingdom and China was over and defined China as a “systemic challenge” to British values and interests.

This was not surprising given that the dominant political thought in most Western countries with regard to China is currently hostile, driven by a new McCarthyism fueled by the United States. And Britain, too, has fallen victim to this poisonous approach to international affairs.

With the current cost-of-living and energy crisis deepening, and a looming recession ahead, it would be logical for the U.K. to take a more constructive attitude toward China, instead of following the U.S. in its policy of containment.

However, as British imperialism has essentially been in a state of slow and managed decline for the last century, the mainstream thinking has always been that Britain could best maintain its position in the world by being closely aligned to the U.S., which is what the British establishment likes to imagine constitutes a “special relationship” between the two countries.

This, for example, was reflected during the time of the Iraq war, when the then Prime Minister Tony Blair stated it pretty clearly, arguing that Britain had to be on the side of the U.S., almost as though the country had no choice in the matter.

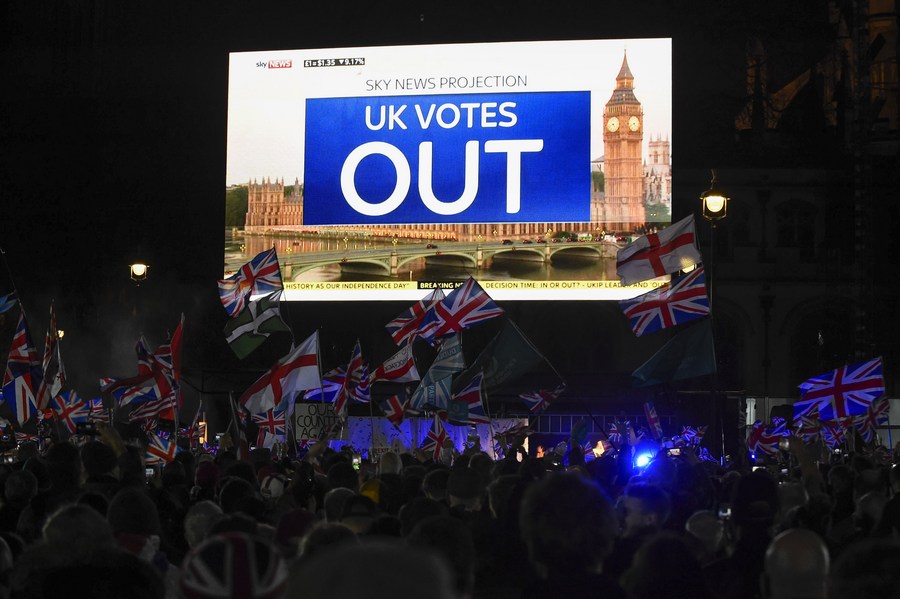

Brexit has only served to worsen the situation as much of the drive for Britain to leave the EU came from those sections of the ruling class which are most strongly pro-American and do not want to be aligned with European countries like France and Germany – that sometimes display a degree of independence.

With Britain coming out of the EU, for these people, the U.S. is the only pillar that’s left for the U.K. to cling to, and a hostile foreign policy toward China is a natural outcome in the current climate.

Some pro-American people seek to disguise that reality by claiming that after leaving the EU, we would become a supposed “Global Britain.” But a “Global Britain” strategy that does not embrace China, the second biggest economy in the world, is a crazy and meaningless one.

However, Sunak’s first major foreign policy speech as prime minister was not entirely negative, as he dialed down the most simplistic Cold War rhetoric against China to a certain extent, and acknowledged China’s significance in world affairs, to global economic stability, and on issues like climate change.

This represents a different approach to that of the many prominent hardliners in the governing Conservative Party, and hinted at his previous keenness to restart the economic and financial dialogue with China – which rightly identified having a reasonably good relationship as being in the U.K.’s national interest.

In describing his government’s vision of facing competitors by means of an ambiguous strategy that he termed “robust pragmatism,” Sunak is trying to please two camps at the same time – the hardliners on the right of the Conservative Party, who want to push an anti-China policy, and the business community, many of whom would still like to have, and need, a good relationship with China.

This latter sentiment is shared by Chinese investors in the U.K. In launching its 2022 Report on the Development of Chinese Enterprises in the U.K. in London on December 8, 2022, the China Chamber of Commerce in the U.K. (CCCUK) noted the wide range of sectors in which their members are invested in matching many of the needs and priorities of the U.K., for example in green and renewable energy, transportation, healthcare, and so on. At the same time, the challenging geopolitical environment was noted, with the increasing lack of transparency in the political, legal, and regulatory environment cited as being of particular concern.

Indeed, the emergence and growth of rightwing populism has already led to an unprecedented gap widening between businesses and the Conservative Party, which hitherto has always been the main party of business in the U.K. It remains to be seen how this emerging political dynamic will play out.

This rightwing of the Conservative Party is quite ideologically driven and has a definite view of how Britain should get out of the economic crisis, which actually amounts to intensifying the attack on ordinary people and going back to the discredited trickle-down economics, which was taken to an extreme during Liz Truss’s short-lived and disastrous premiership.

With Sunak’s background, both as the former chancellor, which meant he had to understand at least some of the economic realities facing the country, and as a former fund manager working with Goldman Sachs and others, his natural inclination would be to conclude that, despite the differences in systems and values between the U.K. and China, we can’t just ignore the second largest economy in the world.

But Sunak is being held back from that approach by the weakness of his position, which stems from the deep divisions, nurtured over decades, within the Conservative Party. So, his talking about “robust pragmatism” essentially means that the prime minister is simultaneously trying to please two different camps. However, the obvious danger he faces in so doing is that he may end up pleasing nobody.

As Sunak said: “we’ll manage this sharpening competition, including with diplomacy and engagement.” I suggest that in dealing with China there should be a return to a grown-up diplomacy, which Britain used to be quite good at in all fairness, and government ministers should put an end to insults and incendiary and inappropriate language for a start.

Second, the government should come to the realization that, whether they like China or not, as one of the great powers in the world, having the second biggest economy, China is here to stay. Therefore, if we’re not going to go to war, then we have to find ways to get along.

Third, not least since we have different ideologies and systems, we should understand that a lack of knowledge and understanding never benefits anybody. And we have a big China knowledge deficit in the United Kingdom right now – so few people in Britain learn the Chinese language and I don’t see evidence of much China expertise in academia, let alone in the media.

Both the U.K. and China are permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, so neither should have an interest in turbulence or conflict in the world, and obviously there are issues that concern everybody, like climate change, the need for sustainability, and such major public health issues as the COVID-19 pandemic, on which our two countries need to work together on good terms.

Keith Bennett is a consultant and analyst on international relations and co-editor of Friends of Socialist China based in London.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +