A Blue Corridor

The Polar Silk Road could be the new trade route to regional prosperity

For businesses using ships as the major means of transportation, the conventional shipping routes from China to Europe, either passing through the Suez Canal that connects the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea or the Cape of Good Hope on the Indian Ocean, are time-consuming and fraught with fears of violence and instability, as well as heavy traffic. In comparison, a new route through the Arctic is much shorter, taking about a fortnight less.

For businesses using ships as the major means of transportation, the conventional shipping routes from China to Europe, either passing through the Suez Canal that connects the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea or the Cape of Good Hope on the Indian Ocean, are time-consuming and fraught with fears of violence and instability, as well as heavy traffic. In comparison, a new route through the Arctic is much shorter, taking about a fortnight less.

The white paper on China’s Arctic policy issued last year calls for building the Polar Silk Road, a new blue economic corridor connecting Asia with Europe along Russia’s Northern Sea route (NSR) in the Arctic. The Russian Government is already developing the NSR, having issued a comprehensive development plan in 2015. In 2017, the volume of cargo that passed through the NSR was over 18 million tons. It is expected to reach 30 million tons this year and 80 million tons by 2024, making it a vital passage to connect the two continents.

A strategic venture

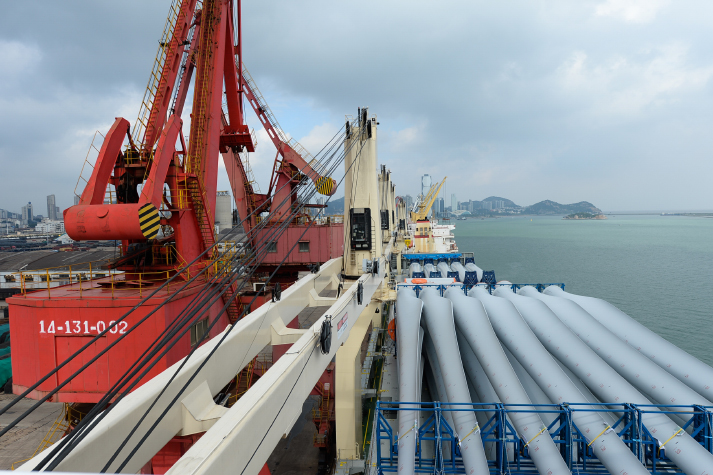

China and Russia already have several cooperation projects in the region. The Russian areas along the Polar Silk Road have abundant gas resources. The Yamal project in Sabetta has Chinese and Russian companies jointly building a liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant with an annual capacity of over 16.5 million tons.

In 2017, China Shipbuilding Research Center and St. Petersburg State Maritime Technical University entered into an agreement to cooperate in new Arctic technologies for ocean research, Sputnik reported. The Polar Silk Road is likely to see other cooperation projects to develop infrastructure and technology in participating countries.

Japan and the Republic of Korea (ROK) are also interested in the Polar Silk Road. On one hand, their energy self-sufficiency is below 10 percent and they are seeking to diversify their energy imports like China. On the other hand, their advanced shipping manufacturing industries can benefit from the initiative. North European countries struggling with insufficient capital for infrastructure construction are also looking forward to related investment projects.

The white paper, China’s Arctic Policy, says the venture under the Belt and Road Initiative will facilitate connectivity and sustainable economic and social development of the Arctic. China’s capital, technology, market, knowledge and experience is expected to play a major role in expanding the network of shipping routes in the region and facilitating the economic and social progress of the coastal states along the routes, it adds.

Politically, the easing of tensions in northeast Asia has improved security along the Polar Silk Road. In the past, the United States’ threats of force against the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) and the prolonged confrontations between the DPRK and the ROK fomented instability in the region, posing greater risks to cooperation and investment.

But the situation eased last year after meetings between the leaders of the two Koreas as well as between DPRK leader Kim Jong Un and U.S. President Donald Trump. These interactions have created a promising environment for the Polar Silk Road.

Hurdles to overcome

However, although the Polar Silk Road has opened up unprecedented chances, it still needs to overcome various challenges. The most prominent one is the lack of political mutual trust among the countries involved. Historical issues and territorial disputes between Japan and Russia, Japan and the ROK, and Japan and China have made their relationships fragile. The Nordic countries have long been skeptical of Russia’s intentions, and the tensions deteriorated after the crisis in 2014, when Crimea held a referendum to break away from Ukraine and join Russia.

In addition, there are differences among the institutions and the legal frameworks of the countries along the routes. Russia, Canada, Norway and Denmark have a long dispute over the delimitation of the continental shelf and the management of the shipping routes. For example, Russia claims that the shipping routes pass through its internal waters and says all passing vessels should accept Russian jurisdiction while in those waters. The other countries say the routes are international waterways. Given such differences, it is hard to reach an agreement.

More importantly, the West has begun to hype up the bogey of the China threat in the Arctic. They portray China as the challenger of the current order. In December 2018, the U.S. Congressional Research Service, the think tank of the U.S. Congress, released a report, accusing China of disrupting the Arctic order and labeling China’s activities under the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative as part of global expansion.

On May 6, at the opening of the Arctic Council, an eight-member intergovernmental forum to discuss Arctic issues, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo alleged that China’s construction activities in the region would create a debt trap for the countries involved and warned them to stay vigilant. The China threat rhetoric, while not representing the mainstream voice, still caters to the prejudice and hostility of some countries and has stymied the advancement of the Polar Silk Road initiative.

Joint advancement

As a blue economic corridor connecting Asia and Europe, the Polar Silk Road could be jointly advanced by the various cooperation mechanisms established under the Belt and Road Initiative.

The initiative’s financing mechanisms, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Silk Road Fund, could provide funding for participating countries with financial difficulties.

Russia and the five most vital Nordic countries along the Polar Silk Road—Norway, Iceland, Finland, Sweden and Denmark—are all founding members of the AIIB. Therefore, the AIIB could be fully involved in the construction of the Polar Silk Road to facilitate investment in infrastructure and financing.

The communication facilities along the Polar Silk Road are poorly developed. Even developed countries such as Norway still face difficulties in building communication networks in high-latitude areas. The experience and technologies developed in Belt and Road cooperation could be applied to improve the interconnectivity of the Polar Silk Road.

The Polar Silk Road should align with the ongoing projects of the Belt the Road Initiative. For example, it could integrate with the China-Europe freight rail network and the China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor to develop joint sea and rail transportation. This would not only deepen Belt and Road cooperation, but also see the Polar Silk Road prosper in multiple fields.

The author is an assistant research fellow with the China Institute of International Studies

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +