A Communal ASEAN Outlook

While the multilateral efforts of China and ASEAN member states in seeking consensus on the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea still remain inconclusive, perhaps the prototype of the China-ASEAN community with a shared future marks the solution to the protracted impasse.

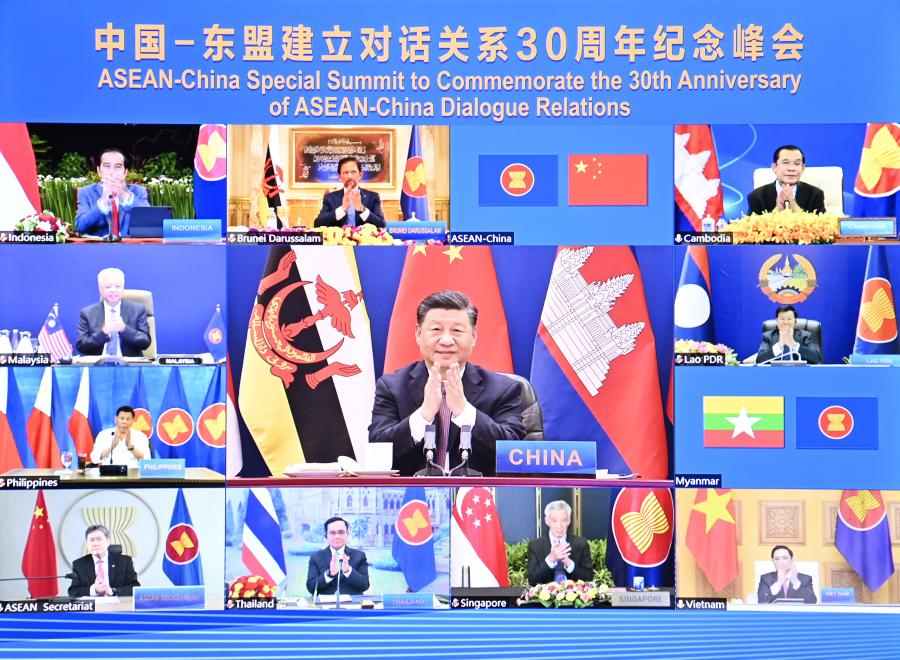

The coming of age of China’s dialogue relations with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) after three decades has borne the most successful model of cooperation in the Asia Pacific. The largely economic-driven relationship has presented the world with a stable, resilient and symbiotic prototype of collaboration, albeit not without the occasional unyielding litmus test of mutual trust stemming from external maneuvers.

Good neighborliness has been the reigning order across the region over the past 30 years. The disputes and crises arising from time to time have thus far been handled with an approach of maximum maturity and mutual respect, substantiated by bilateral negotiations. Against the backdrop of increased meddling in local disputes on the part of the U.S., it has never been an easy feat for the regional bloc to resist the enormous pressure from the reigning superpower to choose sides in its geopolitical power rivalry against China.

Concerted, comprehensive

China, the first ASEAN dialogue partner, to date remains the bloc’s biggest trading partner, as it has been for the past 12 years, while the latter for the first time ever surpassed the EU as the largest trading partner of China amid the global COVID-19-induced economic fallout last year. Over the years, the mutual cooperation has steadily evolved into a successful blueprint of all-round collaboration across the region. This signifies the viability of cooperation between countries of different ideological polities and growth levels.

The wide gamut of new cooperation potential in sectors such as vaccine research and production, digital economy, green economy and blue economy, just to name a few, constitute the beacons of hope for the region’s post-COVID-19 economic recovery. This provides ASEAN with a viable avenue for deepening its cooperation with China, which already has the value chains in place and is open to sharing the benefits with its Southeast Asian neighbors through the various Silk Road initiatives, ranging from the Health Silk Road and the Digital Silk Road to the Green Silk Road.

Parallel to this, the maritime-based blue economy, through teamwork in oceanic endeavors, is the latest initiative added to the list. The most recent ASEAN summit in October adopted the ASEAN Leaders’ Declaration on the Blue Economy, indicating the bloc’s great confidence and determination in promoting the sustainable development of the blue economy and deepening international cooperation. The forging of the China-ASEAN partnership on blue economy, now earmarked as one of the key priorities in the China-ASEAN Strategic Partnership Vision 2030, is undoubtedly the best-timed tool to serve the purpose.

With all the aforementioned in place, the interests and wellbeing of both China and ASEAN are now becoming increasingly intertwined, thus paving the way for the realization of the first community with a shared future template within ASEAN.

The recent announcement of the comprehensive strategic partnership between China and ASEAN proves a major step forward in the pursuit of said community. Its complementarity with the ASEAN Community Vision 2025 in the fields of regional political security, economic development and socio-culture endears it to the bloc in its quest for fulfilling the long-hatched ideals of the ASEAN Political-Security, ASEAN Economic and ASEAN Socio-Cultural communities.

It further provides ASEAN member states with the desired impetus to realize the group’s commitment to the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development—both a parallel and interrelated agenda, the execution of which is getting more challenging by the day in light of the pandemic onslaught.

From the Chinese perspective, the proposed China-ASEAN community with a shared future stretches far beyond merely serving the interest of multilateral economic cooperation by shaping multi-sectorial connectivity. It is an ideal platform to manage regional crises and disputes concertedly, in addition to being conducive to reducing the trust deficit—detrimental to the region’s multilateral cooperation.

Adjusting the angles

With the unrelenting influx of disinformation and prevailing toxic narratives against China in the U.S.-led geopolitical checkmate, it is imperative for China to rev up its communication apparatus by boasting a wider outreach to people across the region. Track-One diplomacy, or official governmental diplomacy, a technique of state action, alone no longer suffices to meet the challenges at hand. Trust deficit can only be stopped by properly extending all-inclusive information to the region’s residents by large. China needs to be well understood—from the right perspective. Incidentally, instead of focusing on the China success story, which in many cases might be deemed very much lop-sided, the sharing of symbiotic experience from the ASEAN angle is perhaps the right adjustment to make, rendering the world’s second largest economy more “lovable” to its neighboring area of 650 million. This puts to the ultimate test China’s soft power, most notably in the skill of communication.

While the ASEAN member states are wary and weary of the saber-rattling of warships from powers outside the region in the tension-filled South China Sea, purportedly safeguarding the rights of free navigation, any efforts to deescalate the face-off tension would certainly be welcomed as refreshing and deemed contributive to the cause of nurturing regional peace and stability. In late November, the Chinese announcement of its willingness to sign the protocol to the Treaty of Southeast Asia Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone—a commitment to keep the region free of nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction—constituted a laudable move well-received by the region. If this were to come true, China would be the first nuclear power making a nuke arms-free commitment to the region. This might help facilitate confidence-building among the ASEAN member states vis-à-vis China on regional security, a matter for which the bloc has thus far been relying heavily on the U.S. to procure.

While the multilateral efforts of China and ASEAN member states in seeking consensus on the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea still remain inconclusive, perhaps the prototype of the China-ASEAN community with a shared future marks the solution to the protracted impasse. Without forsaking the respective sovereignty claim, the platform entity could be empowered through viable programs of cooperation, notably in the sphere of marine-linked endeavors, in the disputed waters. This would help enormously in deescalating the rising tension, thus leaving no room for others to conduct any malicious geopolitical maneuvers which might spark conflict.

Apart from the conventional collaboration on marine search and rescue, safety and security as well as oceanography, the vast potential of maritime-based blue economy embedded in sectors like renewable energy, fisheries, aquaculture, maritime logistics and tourism in the South China Sea would be sufficient to turn the present theater of geopolitical power rivalry into a resourceful ground for China-ASEAN collaboration. Only then can the busiest international shipping lane transform itself from a clash of political waves into a sea of sustainable collaboration.

The author is chairman of the Center for New Inclusive Asia in Malaysia.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +