A Future Beyond Imagination

The renewal and cultural revival of its two mother rivers has made Shanghai more beautiful, and now, it must acquire new industrial muscle as well.

When American historian Jeffrey Wasserstrom came to Shanghai in March 2009, a year before the World Expo 2010, he exclaimed, “Shanghai’s future is beyond imagination.” At that time, Shanghai had carried out riverbank management in some sections of the Huangpu River, one of the two mother rivers of the city, and restored its cultural functions. Over a decade later, perhaps Wasserstrom would exclaim even more as the region along the Suzhou River, the other mother river of Shanghai, has also turned from an “industrial rust belt” with dilapidated urban areas into an innovative public space. Together, the two rivers exemplify urban renewal and cultural revival.

A facelift for Shanghai’s mother rivers

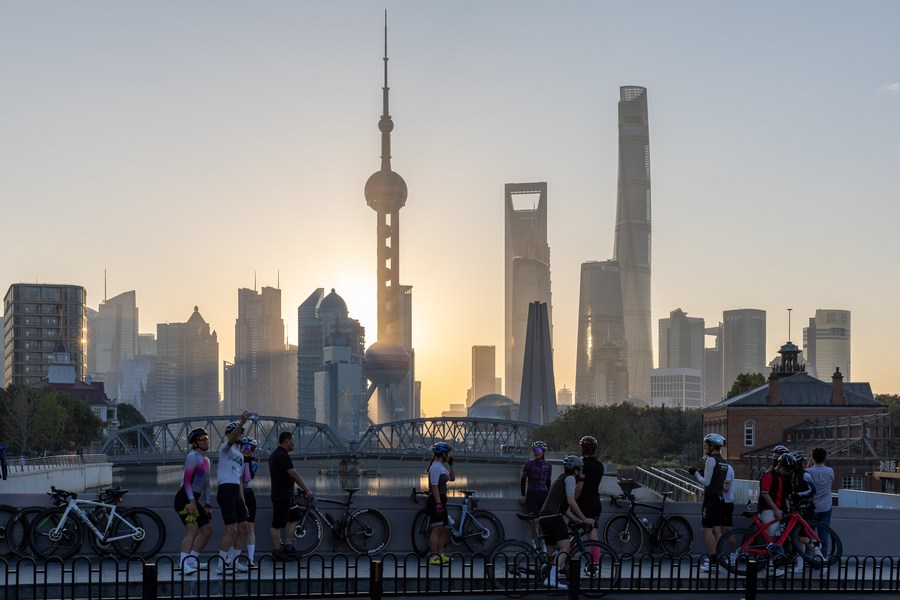

In the past, the main areas along the two rivers were chock-a-bloc with factories with roaring machines, wharfs that were busy day and night, and crowded and noisy commercial and residential areas. The two rivers were heavily polluted and the malfunctioning city struggled to meet residents’ needs. Then in 1990, Pudong, a district east of the Huangpu, was designated a new area that would be a hub of innovation, investment and entertainment. Today, it is arguably the most beautiful urban landscape in Shanghai with the Oriental Pearl Tower, one of the world’s highest TV and radio towers, standing as a towering landmark, complementing the architectural complex on the west bank of the Huangpu.

The transformative changes on both sides of the Huangpu can be attributed to the Shanghai World Expo in 2010 with its “Better City, Better Life” theme, which spurred efforts to turn the riverside area from a production space into a living space with cultural functions. In May 2001, the Shanghai Urban Development Master Plan (1999-2020) was issued to build the city into an international, prosperous, modern, and beautiful metropolis. Some local enterprises like the Jiangnan Shipyard and Shanghai No.3 Iron and Steel Plant were relocated, and the space they left behind was turned into art, culture, and ecological spaces. Shanghai’s Bund area, the historical waterfront area in central Shanghai, was about to apply for world heritage status and a plan was also issued to protect the cultural space.

After the renewal of the Huangpu achieved striking results, the Suzhou was next on the agenda. The river is the birthplace of China’s modern national industry and a testament to Shanghai’s status as China’s largest industrial city. Decades ago its banks were densely packed with flour mills, chemical plants, and machinery and textile factories. Hundreds of thousands of people worked and lived here, and the machines worked day and night. The roaring machines, piles of goods, busy traffic, and random discharge of sewage were like the early scenes at Thames in London or the Seine in Paris.

The urban renewal and spatial governance of the Suzhou kicked off with a new round of Shanghai’s urban planning in 2018 with environmental improvement and cultural revival of the Suzhou River formally incorporated into Shanghai’s urban development. By 2020, the 45-kilometer-long river bank in the core section of the Huangpu and the 42-kilometer stretch in the core section of the Suzhou had been renovated and functionally upgraded, greatly optimizing Shanghai’s spatial structure and laying the basic structure for its future development.

Lessons to be learned

Aristotle once said that men come together in cities in order to live, but they remain together in order to live the good life. This is one of the important sources of the catchphrase “Cities make life better.” It established a new concept of urban development, that is, the purpose of human beings in building cities is not only to increase the population or boost economic growth, but to provide a valuable, meaningful, and aspirational lifestyle. The renewal and revival of Shanghai’s two mother rivers is a vivid practice of this concept. In essence, it is not only about dredging waterways or producing more industrial goods and daily necessities, but about returning the water and the beautiful scenery to the people. However, this is not an easy task as the interests and needs of many parties are involved. In order to reconcile them, Shanghai carried out some explorations, providing a reference for global urban renewal and cultural revival.

During the process, the government needs to take the lead. However, it also needs to have citizen participation in the entire process to balance public interests with private ones. The population and building density along the two rivers are high, and space resources are extremely scarce. Connecting the river banks means turning some spaces that were occupied by companies and communities into public ones, which will inevitably encounter resistance. If the government does not take the lead, this cannot be overcome. However, if the government is too demanding, it will cause more conflicts. So the government departments started from the perspective of the interests of residents and formed some typical cases of success.

Jinyang Lane and Taoyuan Lane, built in the 1920s and 1930s, respectively, are home to typical old-style shikumen lane houses of Shanghai – traditional brick-wood structures with stone gates. When the renovations started, many residents agreed to it at first, but then changed their minds. For example, some residents who had agreed to install flush toilets found that it would make their public areas shrink, so they became unwilling to cooperate. However, after all the residents were persuaded to say goodbye to traditional toilets, their living environment improved.

Another example was the comprehensive renovation of houses in residential compounds. Some residents initially did not think highly of it. However, with the construction of high-quality residential compounds, the residents in an area asked that the wall between neighboring compounds be demolished to create a green landscape belt.

After the master plan was completed, attention has to be paid to policies and mechanism innovation during the implementation. How well the planning can be implemented depends on the skills of the builders. Shanghai has formed a system of community engineers, planners, health specialists, community management consultants, legal consultants, and governance consultants to promote urban space governance.

Liaoyuan Huayuan in Jiangpu Road is a prime example. A block of three old residential compounds with an average age of 30 years, it has an area of 26,000 square meters with 416 households. However, it lacked a decent public space. The planners proposed to remove the walls to open the space and held dozens of meetings to listen to different opinions. Finally, a public space for adults to exercise and children to play in was created. The “pocket garden” on Fuxin Road is another example. Located close to Tongji University, it was originally an 80-meter green belt along the street. The planners added slides and swings and placed colorful geometric figures on the ground to create a “pocket garden” where one can sit and relax.

Future: an innovative city with modern industry

While a dynamic ecological axis has been formed along the Huangpu and Suzhou, it has also led to new challenges. With the focus on ecological governance, public services, culture, and tourism, the industrial functions of urban space have been weakened, leading to problems such as a single industrial structure, homogeneous functions, excessive investment in public resources, and high operation and maintenance costs. These problems are not unique to Shanghai. Looking to the future, once ecological governance achieves results and the layout of public cultural functions is basically completed, new industries will be needed to promote coordinated development of public services and the real economy.

Public spaces need production functions. At present, the Huangpu bank is positioned as a financial, cultural, innovation, and recreational center. However, the fast relocation of production functions has led to a disconnect between production and life, and the areas along the river have become pure public service spaces that “only consume, and do not produce,” increasing the pressure on fiscal expenditures. In the future, the principle of sustainable development should be followed, focusing on enhancing the real economy and industrial functions to turn precious space resources into a goldmine of entrepreneurship and wealth.

Also, the cultural and tourism industry needs to develop rapidly. In the current industrial layout, the two river areas focus on ecology, culture, and tourism, and the main function is to serve the construction of a beautiful Shanghai. There are historical reasons for this as production activities along the riverbank in the past seriously affected the daily life of local people with their pollution and noise. As a result, the new round of urban planning got rid of the industries. In the future, the focus should be put on changing the single cultural and tourism industry structure and re-industrializing innovatively the two rivers to make them an important new sector of Shanghai’s economic development.

Finally, integrated development of industries and living spaces in the areas along the rivers should be accelerated. At present, the problems in the development of the two rivers can be summarized as contradiction between “breaking the old and establishing the new.” That is, after demolishing the traditional industrial structure, Shanghai failed to establish a new industrial system of the same scale, which has led to excessive urban functions and insufficient industrial capacity. In the future, full use should be made of the existing space, and high-end manufacturing, producer services and urban agriculture should be introduced. The planners should also integrate artificial intelligence, big data, and other high technologies to create an ecology suitable for the two rivers and the local people. The future Shanghai should be an innovative city with a complete modern industrial system.

Liu Shilin is president of the China Institute for Urban Governance of Shanghai Jiao Tong University, and director of the research office of China Urban-townization Promotion Council.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +