A Legacy of Reform in Xiaogang

Yan was born in 1973 to a farming family in Xiaogang, a small village in eastern China’s Anhui province. The eldest of five siblings, Yan saw little prospect for his family in the way farming was done in the village, and decided to find out what was out there.

By Zhang Jiaqi

Yan Yushan left home after graduating from middle school, carrying nothing but a few books and the dream of making it in the big city.

The year was 1992, when China’s urban centers began to get a facelift from the country’s renewed efforts of reform and opening up. One of the most drastic transformations was in Guangdong province, where small towns and fishing villages would overnight become metropolises of highways and skyscrapers.

And that was where Yan would flourish, and eventually bring his success back home to Xiaogang.

Δ Xiaogang village on June 11, 2018. [Photo by Zhang Jiaqi/China.org.cn]

From Successes to Aspirations

Yan was born in 1973 to a farming family in Xiaogang, a small village in eastern China’s Anhui province. The eldest of five siblings, Yan saw little prospect for his family in the way farming was done in the village, and decided to find out what was out there.

Arriving in Dongguan, Yan was immediately impressed by the newly paved roads. He got work as a security guard at a Hong Kong-invested company producing electronic parts. Like the city itself, the company grew quickly, moving to new office buildings, workshops, and increasing staff.

“I came here to learn, with an aspiration to be a boss in the future and return to Xiaogang,” he recalled. “So I must observe carefully, and develop the ability to solve problems that others can’t.”

There were many problems beyond those related to security, so Yan kept his eyes open for every production procedures and every corner of the factory. His break came when the factory was behind on filling an order of switch transformers, and faced defaulting on loans.

The factory at the time used conventional production methods, going through long procedures and using much manpower to produce meager sums. Yan noticed some imported machinery that supposedly allowed automated production was left collecting dust, and decided it could be the solution to the company’s crisis.

In his early twenties, Yan had little training, but he did have plenty of time after work. After finally getting the machine to run properly, he asked his boss to put him in charge of the production line. With little to lose, his boss agreed.

Yan would not waste his chance. As the new workshop director, he installed the machine, simplified the procedures, rearranged the workers, and succeeded in producing 2,000 switch transformers in his first day of promotion.

This breakthrough, along with his can-do attitude, made Yan a rising star. Over the seven years he was with the company, he saw its employees rose a hundred-fold, and his own pay making a similar leap. The youth from a remote village was well on his way to becoming a wealthy businessman on the frontiers of China’s economic rise.

But in 1998, on the 20th anniversary of China’s reform and opening up, Yan saw his father on TV delivering his inauguration speech as the director of Xiaogang’s village committee. At that moment, Yan was reminded of why he left home: To find a path for his family and his village toward better lives — as his father once risked his life to do.

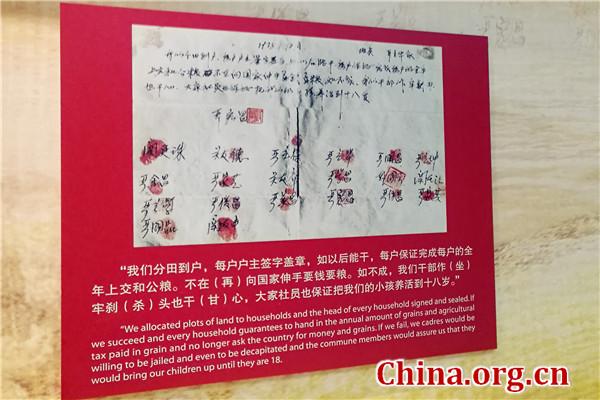

Δ The photocopy of the secret contract signed by Yan Hongchang and 17 other Xiaogang villagers in 1978 is kept

at a museum in memorial of the reformed contract system. [Photo by Zhang Jiaqi/China.org.cn]

From Secret Contract to Making History

One of Yan’s earliest memories was of a grass green jeep parked in front of his house in Xiaogang that drove away his father. At 5 years old, Yan could not understand the significance of the event, but he would later learn that his father Yan Hongchang, along with 17 other villagers, helped to spark a wave of nationwide rural reforms that marked the beginning of China’s reform and opening up.

In 1978, a severe drought befell Xiaogang and the surrounding region. Fearing a famine, the villagers signed a secret contract to divide up their communally owned farmland into individual plots.

At the height of China’s old-school communism ideals, this was a big no-no. The land belonged to the collective, and so did whatever crops it produced. Assigning land ownership to individuals was sure to trigger punishment from the government. Knowing this, the 18 villagers also agreed in the secret contract —penned by the elder Yan— that in case any of them were jailed or executed for their deeds, others would take care of their children.

Fortunately, the authorities saw the merits to their ways. After all, Xiaogang in 1979 produced as much grain as in the previous five years combined, and as much oil crops as the sum of the previous 20 years. The jeep did not haul Yan’s father away as a martyr, but instead held him up as a model. Within a few years, farms across China adopted the principles of Xiaogang’s secret contract. The document now sits proudly in a museum, and the story of the 18 villagers is taught in China’s history books.

Yan always knew he had a lot to live up to. With everything he had learned and accomplished in Dongguan, he decided it was finally time for him to go back to Xiaogang and follow in his father’s footsteps.

Δ Yan Yushan (L) and his father Yan Hongchang. [Photo/The Cover]

From Entrepreneurship to Public Service

Filled with renewed purpose, Yan packed up for home in 1999. His father had promised as village committee director to increase Xiaogang’s annual per capita income to 400 yuan, and Yan planned to contribute by starting a business and creating jobs.

It did not take long for Yan to realize that Xiaogang was no Dongguan, a city that flourished thanks to China’s pilot policies in its reform and opening up. His first couple of ventures — a handicraft company and an electric meter factory — were shut down in 2001, costing all his savings.

Not one to give up, Yan went back to the cities, founding successful businesses in Hefei, Shanghai and Beijing and bringing back the profits to Xiaogang to try again — to no avail.

In August 2014, Yan returned to Xiaogang one last time with a new approach. Instead of starting up a company, the son of one of China’s earliest reform pioneers decided to follow his family legacy into public service, and became a member of the CPC Xiaogang village committee.

To fully commit to his new role, Yan even sold his shares in his companies outside Xiaogang, including the majority stake of a small utility and appliance company in Beijing.

Yan explained his choice as an inherent sense of duty. “Great changes have taken place in Xiaogang, but its economic growth is not so remarkable. My father’s generation has finished their historical responsibilities, and now, our generation must shoulder ours.”

However, his plan for Xiaogang is also a product of his business sense, after multiple attempts at various forms of manufacturing companies. As opposed to creating a secondary industry from scratch, Yan decided to lean on the village’s agricultural heritage and develop its tourism industry.

Instead of raising factories, Yan led the village to pave its streets, plant trees, and renovate its storefronts. Tourism in Xiaogang began to take off, integrating historical tours, folk customs and cultural activities like flower-drum dance, and the picking of fruits and vegetables.

This year, the village’s tourism industry is receiving a boost from the 40th anniversary of China’s reform and opening up. Yan estimates that Xiaogang, as a historical site of the reform, has already received around 500,000 visitors so far this year.

To bring more convenience to the visitors and local businesses alike, Yan launched an e-commerce platform, searching for and eventually attracting commercial tenants to 33 vacant stores at visible locations to present specialty products from Xiaogang and other areas.

As the person in charge of poverty alleviation and the village’s Youth League, Yan is also motivating the next generation of Xiaogang natives to become entrepreneurs. To help them along the way, he is making efforts to implement various reforms for the village, including land rights, contract rights, and management rights of rural lands.

In addition, Yan is also clearing obstacles he personally faced trying to start businesses here, reforming the shareholding system in a collective economy, turning rural resources into assets, capital into equity, and farmers into shareholders.

“People generally believe that the Xiaogang spirit implies the guts to think, to act and to be the first mover,” he said. “In my interpretation, it also implies unity and collaboration, without which the agreement in 1978 wouldn’t have been possible at all.”

His efforts have led to preliminary outcomes. During these few years, the number of villagers leaving as migrant workers decreased from 1,000 to 600, as more and more youths came to participate in Xiaogang’s development.

“The future of Xiaogang relies on Xiaogang people ourselves,” Yan said. “Everyone should bear in mind that they are Xiaogang people, and should get involved and make contributions for the vitalization of Xiaogang.”

Source: China.org.cn

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +