A Turning Point for China-EU Relations?

A complex mix of economic dependencies, geopolitical considerations and longstanding diplomatic engagements is what defines China-EU relations. The core dynamics of these relationships are determined by broader strategic interests and the collective will of EU member states.

The rise of far-right political forces in the European Parliament elections in early June has caused political turbulence, even shaking the global political landscape. With the ongoing strategic competition between China and the U.S., the persistent Russia-Ukraine conflict and renewed conflict in the Middle East, all eyes are on the future direction of the European Union, a bloc of 27 countries in Europe and a major global power, and its potential impact on international relations.

From China’s perspective, while the political changes within the EU may have two positive effects on China-EU relations, they are unlikely to fundamentally alter the bilateral relationship.

First, the far-right parties in Europe generally are not “opposed” to China. Among the major political parties in Europe, the far-right is one of the few openly critical of the EU’s close alignment with the U.S. in its foreign policy toward China.

Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) from France’s populist right-wing National Rally Party condemned former U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s 2022 visit to China’s Taiwan Province, considering it a provocative action. Some members of Germany’s far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party have expressed their support for China’s Belt and Road Initiative, an endeavor to boost connectivity along and beyond the ancient Silk Road routes first proposed by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013.

Additionally, far-right parties often adopt different, non-traditional priorities, including a lesser focus on human rights and values, which may reduce tensions between China and the EU on these issues.

Second, the rise of far-right parties compels the EU to focus more on internal affairs. This shift includes actively addressing voter demands and managing the challenges far-right parties introduce. The parliamentary election results have already led to political repercussions, including the dissolution of the French Parliament, also known as the National Assembly. For the foreseeable future, the far-right will pose considerable challenges for the EU, influencing its moral foundation and priorities. An internal focus may, in turn, lessen some diplomatic pressures on China.

But despite the recent election results, the overall trajectory of China-EU relations is unlikely to see any major changes. This continuity can be attributed to several key factors that transcend the immediate electoral outcomes.

The core dynamics

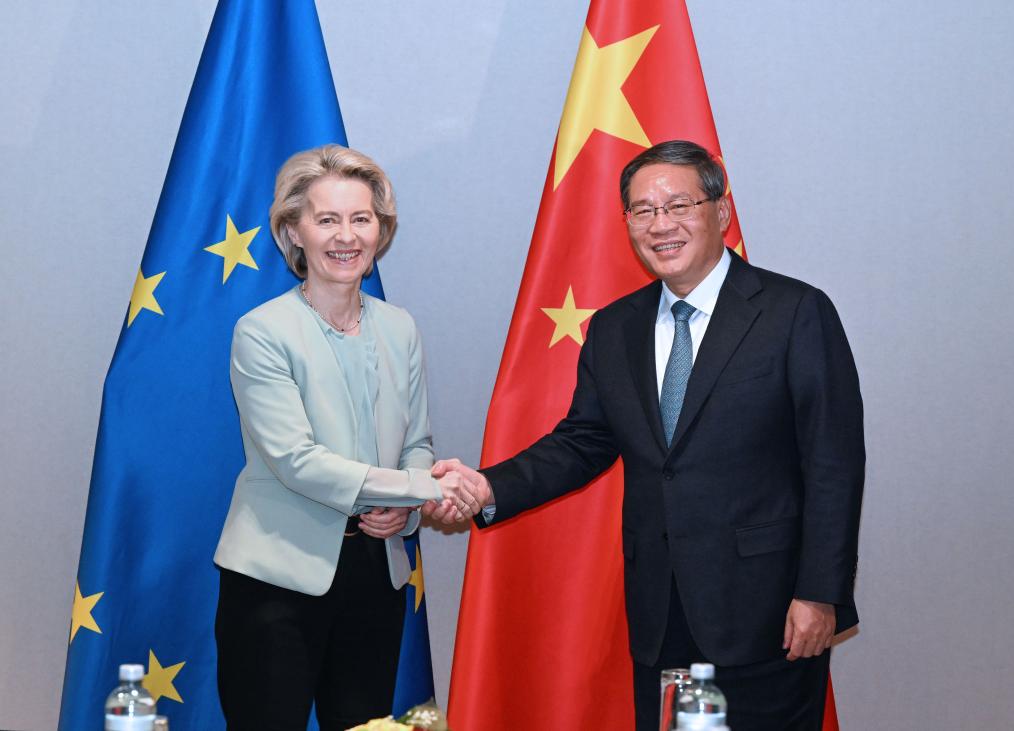

The traditional major parties maintain a majority in the European Parliament, preventing their far-right counterparts from dominating the legislative agenda. For instance, the conservative European People’s Party (EPP), known for its tough stance on China, impacting the EU’s foreign policy, remains the largest parliamentary group. EPP’s Ursula von der Leyen, the current President of the European Commission, is set to seek another term as president this month. The re-election of MEPs who are critical of China further underscores this continuity.

Furthermore, it’s important to understand the scope of the European Parliament’s powers within the EU’s institutional framework. Even though it is the only directly elected body in the EU, its functions are primarily consultative and legislative, focusing mainly on internal EU affairs. The parliament does not have direct decision-making authority in foreign policy and lacks the right to initiate legislation, which limits its influence in these areas.

Instead, the parliament mainly amends and votes on proposals from the executive institutions rather than originating them. Foreign policy decisions, including those concerning China, are made collectively by the EU member states and require unanimous consent from all 27 members. Consequently, even a European Parliament with substantial far-right representation cannot unilaterally influence, let alone shape, EU foreign policy.

Then there are the structural factors governing China-EU relations, which extend beyond the parliament’s domain. A complex mix of economic dependencies, geopolitical considerations and longstanding diplomatic engagements is what defines these relations. The core dynamics of these relationships are determined by broader strategic interests and the collective will of EU member states, rather than the changing composition of the European Parliament.

From the European perspective, then, several key interests sustain China-EU relations and prevent Europe from fully aligning with the U.S.

These include the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict, where Europe hopes China can and will play what the EU sees as a constructive role—or at least avoid siding with Russia. Also influencing Europe’s stance is the concept of strategic autonomy. This concept refers to the EU’s ability to act independently in its foreign policy, security and economic affairs, minimizing reliance on other powers like the U.S.—or China. Championed by France, it has received mixed reactions across the continent.

Additionally, the potential necessity to counter a re-elected Donald Trump in the U.S. looms large in European strategic calculations. And then there are global governance issues, particularly those related to climate change, which further underscore the importance of maintaining a functional relationship with China.

From China’s perspective, Europe is an important counterbalance to U.S. containment efforts and an important factor in China’s continued development. Leveraging Europe as a strategic partner offers advantages for China in its dealings with both the U.S. and Russia.

Neither friends nor foes

China-EU relations are characterized by mutual interests and pragmatism, rather than affinity or friendliness. This perspective was articulated by Jean-Yves Le Drian, the former French Foreign Minister, during his 2021 visit to the U.S., where he indicated that, in French eyes, China is neither a friend nor a foe.

Another structural factor impacting China-EU relations is the China-U.S. relationship, with China-EU ties greatly influenced by the U.S. as a third party. For example, the election of Donald Trump as U.S. president in 2016 led to an improvement in China-EU relations.

The strategic competition between China and the U.S. harms China-EU relations. The overall U.S. influence on the EU surpasses that of China, and it can effectively pressure Europe to align with its China policy.

Improving China-EU relations, while feasible, faces challenges due to fundamental differences and external pressures. For Europe, meaningful progress could be achieved by respecting China’s governance model and refraining from trying to impose its own values onto the country. Supporting China’s goal of reunification, opposing “Taiwan independence” and endorsing the country’s position in the South China Sea are stances that, even though complex and having geopolitical implications, could foster mutual understanding.

The EU might also consider resisting U.S. strategies that attempt to contain China’s technological and economic expansion. This could include the bloc deliberating on the export of photolithography machines to China and reevaluating the restrictions some of its countries have placed on companies like Chinese tech titan Huawei, mainly concerning the use of its equipment in their 5G networks.

Refraining from imposing restrictions on Chinese electric vehicles and other innovative products entering the European market would also signal a commitment to a cooperative relationship.

In the coming years, certain events might lift China-EU relations, such as Trump winning another term, which could drive a U.S. foreign policy style of unilateralism, leading to shifts in U.S. engagement in global conflict and perhaps ending the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Such an outcome, however speculative at present, would reduce a major point of tension between China and the EU.

Alternatively, if Germany’s AfD enters the national government in 2025, or far-right parties win the French presidential election in 2027, China-EU relations might see improvement. Otherwise, relations will likely remain challenging—but not entirely broken.

The author is a visiting political scholar in France and a researcher at the China Institute under Fudan University in Shanghai.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +