Americans First, What About the Others?

The Declaration also lays down the justification for war, namely that it is deemed to be ‘necessary’. This has thus provided the foundation for the 92 wars that America has fought since its first declaration of war in 1776.

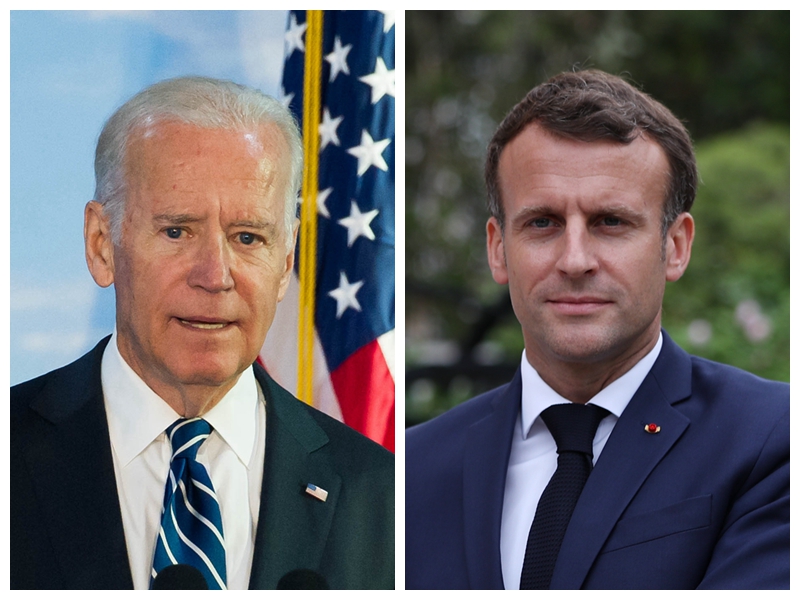

Last month it was the Afghans left to their fate by the Americans. This month it is the French, the nation that gifted America the Statue of Liberty. In protest, they have withdrawn their ambassador from Washington.

I confess not to fully understand the complexities of American society and politics. Brought up on Disney and American culture as a child in the United Kingdom, travel to American now feels like going home. I count Americans amongst my very closest friends. Open, generous, and welcoming, their hospitality towards foreigners matches that I have experienced in China; equal first. Perhaps, in the case of Americans, this is because of their Christian heritage. After all, Christ taught ‘Love each other as I have loved you’ and ‘Do to others as you would have them do to you’.

So why is the love and concern for others expressed by individual Americans missing in American foreign policy? A good place to look is The Declaration of Independence, 1776. And Kenneth White, a professor at Kennesaw State University, is an excellent guide although he might draw conclusions that differ from mine.

The Declaration was exceedingly carefully crafted. It had to be. The founding fathers of America needed to appeal to the French to become allies against the British. (‘Fathers’ is apposite since there were no women signatories.) In practice, of course, The Declaration of Independence was a declaration of war, fuelling the American Revolutionary War which ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783. This followed the retreat of the British militia to Yorktown, Virginia, and a successful siege of the city by allied French and American forces. How ironic, therefore, that 238 years later the US would drop the French and join the British in founding the Australia-UK-US alliance (AUKUS), a military alliance that brings nuclear submarines into the Asian Pacific region.

The second sentence of The Declaration speaks of ‘self-evident truths’: that ‘all men are created equal’ with ‘unalienable rights’ to ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’. It has been suggested that Thomas Jefferson, the principal author of The Declaration, was unclear as to what kind of happiness he had in mind. However, George Washington, in his first Presidential Inaugural Address in 1789, equated virtue with happiness and virtue with the altruistic serving of others. This corresponds directly with the concept of benevolent governance, virtue, and integrity in Confucian thought, and could explain the generosity individually exhibited by both peoples.

‘Life’, as used in The Declaration, not only preferences human life to death but relates both to the community and to the individual. It makes clear, elsewhere, the separation of the human from the divine and the state from religion. This raises the possibility that, in contrast to the Confucian tradition, virtue in governance and individual life can be judged according to different moral criteria.

Liberty, and equality too, mean different things than in China. Liberty refers to freedom from state interference except over matters to which the people explicitly give their collective consent. Equality denotes treatment as a human being, as opposed to other species over which, according to the Bible, Man has dominion. The Declaration, therefore, prioritises individual interests above collective ones and has no concern with equality of outcomes. For Americans, not wearing a mask in a pandemic and living in the most unequal country in the developed world are both manifestations of human freedom. Socialism is anathema as is China’s commitment to ‘common prosperity’, government initiated sharing of wealth.

The Declaration informs our understanding of America’s international politics as well as individual behaviour. Deliberately entitled ‘The Declaration’, rather than ‘A Declaration’, the claim is that it contains eternal and universal truths. Professor White opines that The Declaration, therefore, makes ‘the case for America as a symbol of universal human rights’ and ‘presents a standard by which we [America] can judge the fairness of the treatment of all nations’.

The Declaration states that Americans are ‘one people’, thereby creating a political us and them perspective. While recognising the divisive nature of this dichotomy, when discussing US foreign policy Professor White compares it favourably to the situation in ancient Greece. In Greece, a foreigner was viewed as ‘an enemy not yet killed or enslaved’ while, to America, the stranger ‘is a possible friend or a possible enemy’. To determine friend from foe, America must talk to foreign governments ‘even if we do not like them’, as one of Professor White’s students made clear. In the words of The Declaration, it should pay ‘decent respect to the opinions of mankind’.

The Declaration, therefore, makes America judge over the behaviour of all other nations based on principles that The Declaration declares to be universal. Translated into modern foreign-policy-speak, these are the shared values that the AUKUS Pact is ostensibly meant to defend. The Declaration also lays down the justification for war, namely that it is deemed to be ‘necessary’. This has thus provided the foundation for the 92 wars that America has fought since its first declaration of war in 1776.

Born out of war, the US subsequently fought the American Civil War and the so-called ‘Indian Wars’ to carve out its place on the American continent. Through global wars it has built its economy and, especially following 1945, established global institutions that reflect its ‘universal values’. It even employs the language of war to manage domestic policy: the War Against Poverty; the battle against the pandemic; and the attack on the Capitol. Dividing the world into two, to paraphrase President George W. Bush in November 2001, “You are either with us or against us.”

Insecure, without a culture and homeland stretching back five millennia, America feels the need to continue to fight for its place in the world, despite being the largest economy. The core value of individualism means that it cannot conceive of a community of nations without itself as judge over others. Thus, with the UK and Australia as client states willing to carry weapons into Asian Pacific region and confront a phantom enemy, America willingly sacrificed the French and 200 years of friendship.

The article reflects the author’s opinions, and not necessarily the views of China Focus.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +