An Enigma with No End Game

Ten years after the Global Financial Crisis, where are we, and what happens next?

It is often easier to look at an incident in isolation rather than against its broader context, but looking at a tree will not tell you how big the forest is. Unfortunately, the Global Financial Crisis is just one tree in an increasingly dense forest of financial crises. These incidents have been increasing in frequency and global impact. However, as the financial and political paradigm continues to evolve, but our metrics and solutions are not keeping pace.

Since the Industrial Revolution the world has seen an unprecedented growth in per capita income and living standards. Based on an IMF study by Angus Maddison since the 1800’s GDP per capita has gone up over 6,000 percent.

There has also seen dramatic increase in the number and global impact of financial crises. If you looked at the chart produced by Deutsche bank of financial crises since the 1800’s you would see a massive increase in the number and pace of crisis leading to today. If it was an electrocardiogram the world would be clearly having a heart attack.

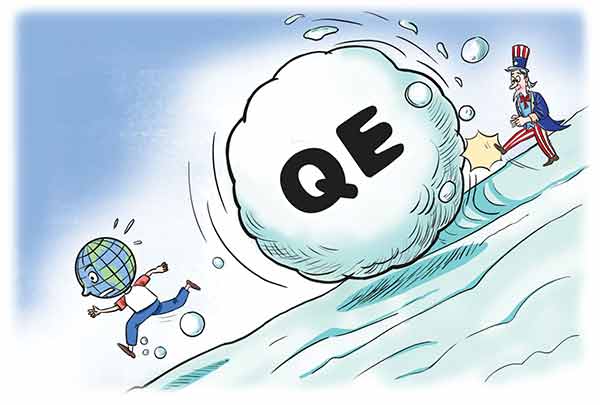

Δ Ten years since the global financial crisis, the world economy seems to be moving toward stabilization, but the risks, rather than declining, have increased significantly

Since the 1800′ there has seen a dramatic reversal in the investment of tangible vs. intangible assets. A Wall Street Journal chart based on research by economists Carol Corrado and Charles Hulten, shows that since 1977 the rate of investment in tangible and intangibles has inverted.

According to Leonard Nakamura, an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia,

“Altogether, companies in the U.S. could have more than $8 trillion in intangible assets …. That’s nearly half of the combined $17.9 trillion market capitalization of the S&P 500 index.

These days, companies put far more money into nonphysical assets, such as customer databases, than they do in building new factories. Companies invested the equivalent of 14 percent of the private sector’s gross domestic product in intangibles in 2014, according to research by economist Carol Corrado. The investment in physical assets was about 10 percent of that sum.”

According to David Post, who leads the Sustainable Accounting Standards Board’s (SASB) team of sector analysts, in an interview with Christopher P. Skroupa on Nov. 1, 2017:

“Intangibles have grown from filling 20 percent of corporate balance sheets to 80 percent, due in large part to the expanding nature, and rising importance, of intangibles, as represented by intellectual capital vs. bricks-and-mortar, research and development vs. capital spending, services vs. manufacturing, and the list goes on.”

This example encapsulates the existence and value of Apple, a trillion Dollar company based on 98 percent intangibles, consisting of brand, research and IP, but which raked in 87 percent of the profits from cell phones sales worldwide in 2017.

Volatility Fueled by a Lack of Metrics Leading to Speculation

Classical capitalist economic theory emphasizes the need for transparency of information and understanding of valuation. Tangible assets fit this model and land, factories, equipment, inventory, distribution, logistics etc.… can be easily understood and valued with the metrics we have. However, we lack accurate metrics to value intangible assets like brand, research and IP, making them more or less “pigs in a poke”. The result has been a series of speculative bubbles.

A smaller percentage of the world, dominated by the West, controls and drives a larger percentage of its wealth, which is being created in the East.

Half of the world’s total wealth is held by 1 percent of the population, including 84 percent of the world’s stocks.

The U.S. and Europe represent 10 percent of the world’s population but hold 60 percent of its wealth. Emerging and developing nations have over 85 percent of the world’s population and just under 60 percent of its GDP (PPP).

The 24-hour non-stop churn of financial markets allow those with money to pursue investment yields around the clock, but it just means that investment is driven increasingly faster, and by a smaller number of people. These money managers create volatility as they drive prices for equities, companies and assets up and down.

The combination of concentrated wealth, shifting markets and financial opportunism are like tectonic plates, which are driving global political and economic friction.

What Drives our Markets has Changed

The nature of what drives our economy has changed dramatically from individual necessities like food, water, shelter and clothing, collective necessities like power, sewage, transportation, education, communication, medicine and child and elder care, to choices. These choices focus primarily on the artificial veneer of our existence, in terms of how we define ourselves, from clothes, shoes, handbags, jewelry and cell phones to jobs, houses and cars. The growth of choice as the main economic driver for emerging and developed nations has created more volatility and is partially why intangible assets now dwarf tangible assets. However, choice is fickle and we’ve seen how a Fortune 500 brand can easily lose its luster overnight due to controversy or changing public perception.

The Domination of the Trade Dollar has Become an Economic Drag.

The dominance of the U.S. dollar as the facto trading currency has grown beyond its competence. While it facilitates private transactions, it is fracturing national economies. Developing and emerging countries that are forced to borrow in dollar denominated debt by credit markets are then at the mercy of currency devaluations and market volatility. Argentina, Turkey and Ukraine are clear examples of this.

Technology Is Changing our World and its Future

Technology will be responsible for eliminating between 1/3 and 1/2 of existing jobs in the next 12 years. Given the magnitude of these numbers, people should expect political, economic and cultural changes in line with the Industrial Revolution.

Conclusion

Looking back at the Global Financial Crisis 10 years on, it is tempting to try to explain it in terms of greed and lax regulations, but it is probably more useful to start thinking of it as part of a pattern of increasingly frequent financial crises. These crises have become the norm rather than the exception. There are many drivers of this new reality and some have been mentioned above, but they are by no means exhaustive. Just like global warming, there are many variables which contribute to the phenomenon. The question, at this point is, what is the best approach to deal with an enigma with no seeming endgame. Some say “faith” in the free market will solve everything, while others point to pragmatic planning and action. Given what we’ve seen in history, the answer seems closer to the latter.

This is not to say the future is bleak. To the contrary, the future will be influenced by what we do, but that does not include clinging to old approaches in the hopes they will solve our new challenges.

Einar Tangen is a political and economic affairs commentator, author and columnist.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +