BBC Anti-China Bias Exposed

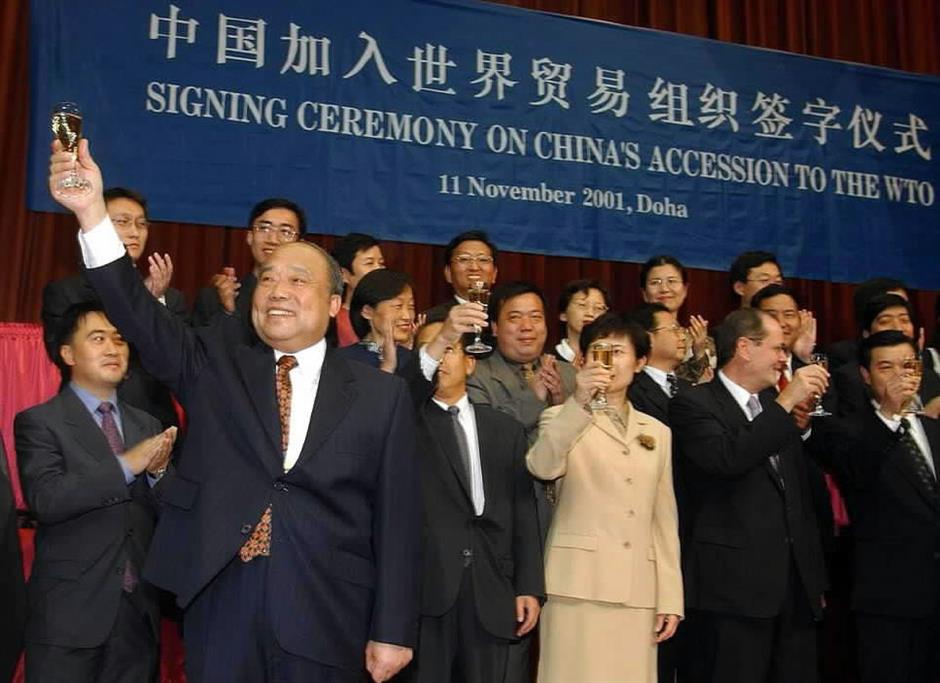

Did the BBC really compare China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) with the September 11 terrorist attacks?

On the 20th anniversary of China joining the World Trade Organization, the BBC ran an article titled “How the West invited China to eat its lunch.” As the title suggests, China’s admission into the WTO is viewed as something detrimental to Western nations.

BBC economics editor Faisal Islam begins by comparing the landmark event on 11 December 2001, to the worst terrorist attack in living memory. “There were two events in late 2001 that shook the axis of the world,” he wrote. “[As] the world was preoccupied with the immediate aftermath of 9/11… the World Trade Organization (WTO) was at the centre of an event that was to cast as strong a shadow over the 21st century, changing more people’s lives and livelihoods than the attacks on America.”

China’s entry into the WTO was rightly described by Faisal Islam as an event of “epic geopolitical and economic importance”. But, likening it to a terrorist attack that claimed almost 3000 lives is in poor taste, if not in direct breach of the BBC’s editorial guidelines.

Before getting to the heart of the issue, let’s briefly consider the notion that the world was “preoccupied” when China’s application was granted. Such a choice of words supposes that the application procedure may not have been sufficiently scrutinized. The inference is that China’s entry may not be legitimate.

Regarding the elephant in the room, namely comparing China’s admission into the WTO with a murderous terrorist attack, two questions arise. The first being: How was such a claim allowed to pass? Second, and more importantly: Why was such a comparison made in the first place?

In order to understand why the author views China’s entry into the WTO as such a terrible event, we must dig a little further into the article. Mr. Islam acknowledges the belief among Western economists and political actors that economic freedom usually leads to political change. Quoting former US President Bill Clinton, he notes that economic freedom is one of democracy’s most cherished values and thus it was hoped that WTO entry would enable “the world’s most populous nation to follow the path of political freedom”.

Such an admission reveals why certain actors are unhappy with China joining the WTO. The intention was never to allow China to get rich and pursue its own developmental path. The aim was to grease the wheels of change and eventually assimilate China into the US-led economic order.

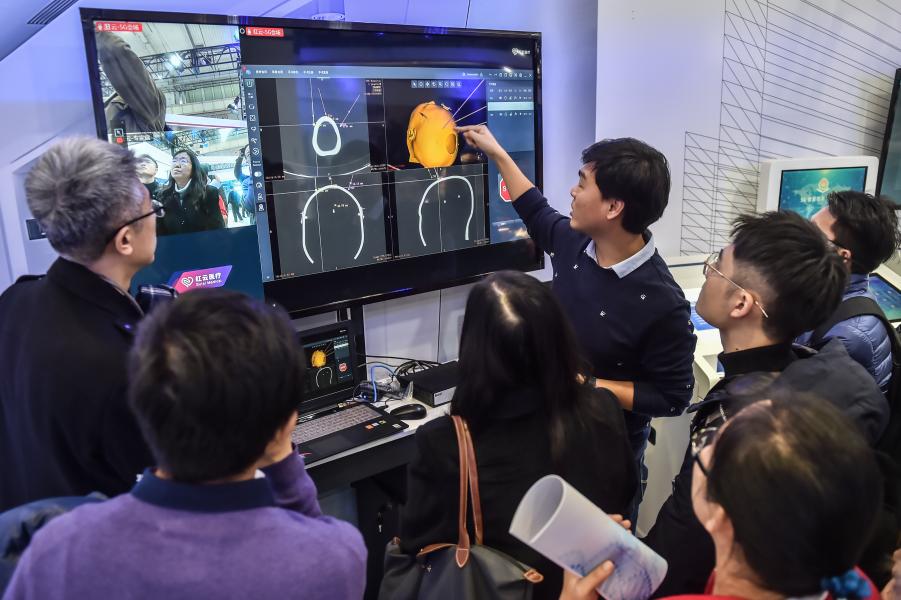

That China failed to become a Western-style democracy is not the only reason for such anger and upset. Appearing to add further insult to injury is that China provides tangible proof that another developmental path is in fact possible. Quoting Charlene Barshefsky, the US trade representative responsible for negotiating China’s WTO deal, the author notes that “China’s economic model ‘somewhat disproved’ the Western view that ‘you can’t have an innovative society, and political control’.

This is considered a big no-no. Regardless of how much followers of Milton Friedman and the Chicago-school carp on about the benefits of competition in the market, there is an unspoken understanding that ideological competition cannot be tolerated. The domino theory, based on the belief that if another path is proven successful it will persuade others to follow, naturally represents an existential threat to the Washington consensus. Such has been the guiding principle behind so many US-led economic sanctions and even military intervention against socialist-leaning nations.

Back to the article in question. The author touches on what is possibly the main reason why so many find China’s WTO membership troublesome. “China has used WTO membership to go well beyond its earmarked role as workshop to the West.” This is a shocking admission. The issue here is that China appears to have ‘risen above its station’. It has stopped serving merely as a provider of cheap labour to the West and has instead grown to become capable of competing in the most advanced and world-changing industries. Seemingly, all would be right with the world if only China had continued to deliver, in the words of the author, “plastic gubbins and cheap tat.”

What surprises me most about this article is not the author’s views but the platform upon which they are presented. Perhaps I have a misplaced sentiment that views the BBC as beyond the corporate landscape of click-bait that has come to govern news media in the 21st century.

A glance at the BBC’s governing charter only furthers my confusion. Indeed, its editorial code of conduct states its mission as “To provide impartial news and information to help people understand and engage with the world around them.”

Is an article titled “How the West invited China to eat its lunch” impartial? Furthermore, how does likening China’s entry into the WTO with a devastating terrorist attack help people better understand and engage with the world?

The article reflects the views of the author and not necessarily those of China Focus.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +