Beyond the First Thrill of Chang’E 4 Moon Landing

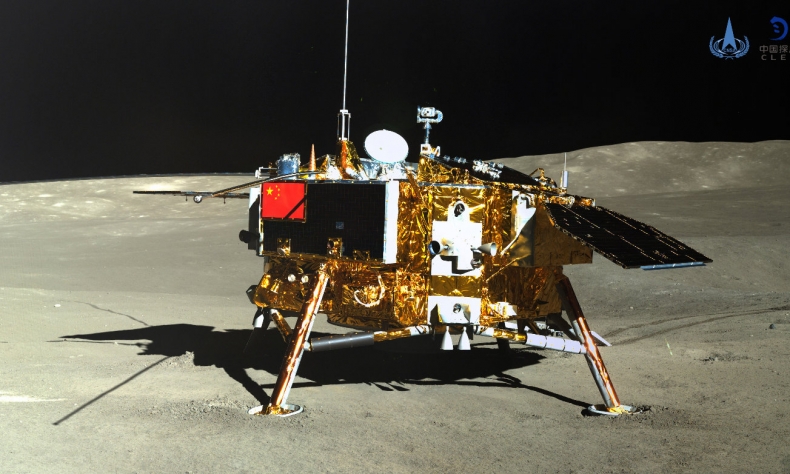

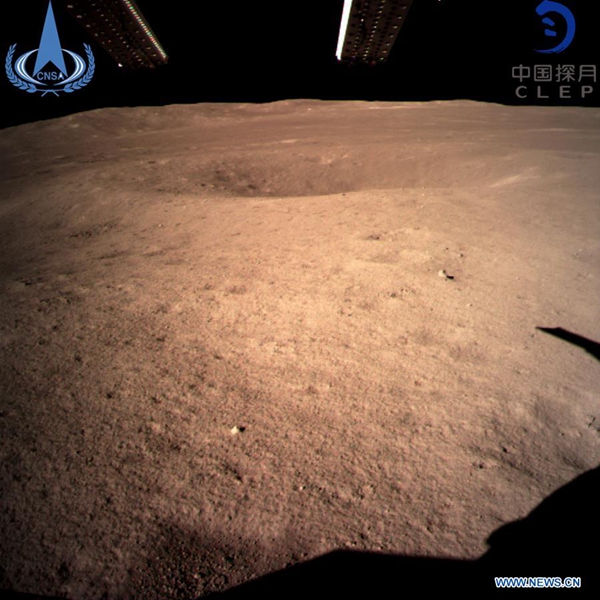

On Jan. 3, 2019, China firmed its place in the history of spaceflight. At 10:26 a.m. Beijing time, a collective sigh of relief was heard in the Beijing Aerospace Control Center, as the Chang’e 4 space probe touched down successfully on the far side of the moon.

The far side is not dark, as is sometimes suggested in popular writing or famous song lyrics. The moon’s orbit around the Earth exposes its far side to sunlight just the same as it does the near side. It is therefore logical that one of the Chang’e 4 instruments will analyze the solar wind — the highly energetic particles continuously flowing from the sun — and its impact on the moon.

Many have questioned the mission’s significance and wondered whether this would spawn a new space race. I believe that China will most likely simply stick to its technology benchmarking. But other space-faring nations may well consider China’s increasing technological prowess as a reason to rekindle their own interests in developing the moon for scientific, commercial, and strategic purposes.

In terms of the technology involved, landing an unmanned probe on the moon’s far side required the launch of a support probe to a location well beyond the moon to relay any communication from Earth. Because of a phenomenon known as ‘tidal locking,’ on Earth we only ever see the moon’s near side.

A remotely controlled soft landing on the moon requires similar technology capabilities as would a future robotic Mars mission. Given the time it takes for any command to travel from the Beijing control center to the lander, the probe had to be autonomous in choosing the most suitable landing site. Having descended to about 100 meters above the surface, it hovered momentarily to assess the suitability for an unimpeded landing below.

But the Chang’e 4 mission is not all about technological proofs of concept. Scientifically, the far side of the moon is also of great interest to lunar scientists. It is heavily pockmarked by deep craters caused by asteroid impacts, some of which were attracted by the moon’s gravity and thus prevented from impacting Earth. On the near side, huge lava flows have partially filled in older impact craters: these are the “seas” one can see from Earth.

The probe’s landing site within the South Pole – Aitken Basin is the moon’s oldest and deepest impact crater. The composition of the crater floor could help scientists date the period of heavy bombardment by asteroids, associated with the early formation of our solar system, and determine whether those asteroids may have carried the seeds of life.

Some of these major impacts may have thrust up material from deep inside the lunar mantle. Many lunar scientists believe that the Earth–Moon system formed from the same material, so analysis of these rocks could also shed light on the formation of the early Earth.

However, one of the most exciting questions scientists would like to answer, to determine the age and composition of these original materials, will not be addressed, since Chang’e 4 does not have the right equipment on board and the landing site is not ideal.

These questions will indeed require a return mission, and the Chang’e 5 and 6 are slated for launch in 2019 and 2020. Both will be sample return missions, but neither has thus far been dedicated to returning a rock sample from the far side. Chang’e 5’s landing site is to be a large, elevated mound in the northern Oceanus Procellarum, known as Mons Rumker, on the moon’s near side.

The moon’s far side is a radio-quiet location, continuously shielded from humanity’s radio transmissions. The Chang’e 4 mission will therefore employ experimental low-frequency radio technology. In addition, the first lunar biosphere experiment, designed by university students from across China, will employ a can of silk worm eggs, potato seeds, and Arabidopsis—a flowering plant used widely in space research.

Engaging university students in real research opportunities such as this is a necessary step in developing a science-literate population capable of making informed decisions through critical thinking. The Chang’e project, with its future-looking progression, is indeed reminiscent of China’s key goal to become a world leader in science: created in China.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +