BRICS Dependent on Free Trade for Development

This by itself makes it a key international event – a type of equivalent of a G7 for developing countries. But BRICS represents a greater proportion of world economic growth than the advanced G7 economies.

By John Ross

The leaders of the BRICS countries – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – meeting in their annual summit this year in Johannesburg represent 41 percent of the world’s population. This by itself makes it a key international event – a type of equivalent of a G7 for developing countries. But BRICS represents a greater proportion of world economic growth than the advanced G7 economies.

As this economic reality underpins BRICS stability, and its role in current international economic developments, it is important to accurately assess the economic potential of the grouping. To avoid any suggestion of using sources biased in favour of BRICS or China, this will be done here using IMF data. These economic trends also show clearly why BRICS has a joint interest in maintaining a World Trade Organization (WTO) based global economy.

BRICS Growth Potential

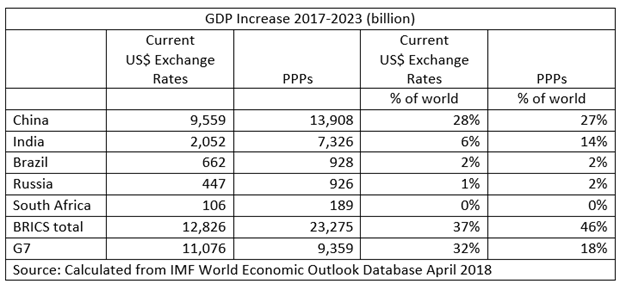

Starting with IMF projections of BRICS growth, Table 1 shows that at current exchange rates BRICS will account for 37 percent of world growth in 2017-2023 – compared to 32 percent for the G7. However, even this advantage significantly understates the real lead of the BRICS economies in terms of actual increases in production and sales of goods and services – and therefore their importance for companies.

This is because lower wages in developing economies means goods and services can be sold as profitably, or even more profitably, in these countries at lower prices than the same goods and services in developed economies. Current exchange rates therefore underestimate actual production and sales in many developing economies – the branch of economics dealing with this is the study of purchasing power parities (PPPs).

Analyzed in PPPs, which are therefore a better guide to the increase in the volume of increases in production and sales of goods and services than current exchange rates, the growth lead of the BRICS economies is decisive. In 2017-2023 in PPPs the BRICS countries will account for 46 percent of the world increase in GDP compared to only 18 percent in the G7. Therefore, BRICS economies, particularly China and India, are a far more dynamic market for companies than are the G7.

It is this economic reality which gives stability to the BRICS group. As will be demonstrated, it also creates strong common interests.

Table 1

Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction

The BRICS, once again led by China and India, have greatly benefited from globalization. Both China and India maintained rapid growth even after the international financial crisis. From 2007-2017 China’s annual average per capita GDP growth was 7.7 percent and India’s 5.6 percent – compared to 1.0 percent in Germany, which had the most rapid per capita GDP growth among G7 economies.

The ability of the largest BRICS economies to maintain rapid growth has led to huge steps forward in living standards and rapid poverty reduction. From 2007-2017 China’s annual average total consumption growth, in inflation adjusted terms, was 8.5 percent and India’s 7.3 percent – compared to 2.2 percent in Canada, which had the fastest G7 consumption growth.

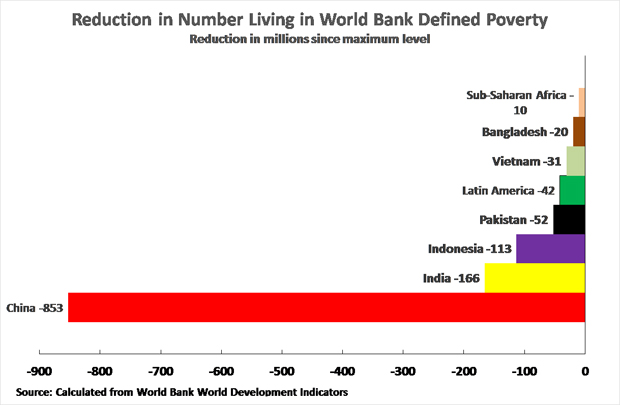

Regarding poverty reduction, as Figure 1 shows, compared to peak levels, China reduced the number of people living in World Bank defined poverty by 853 million and India by 166 million – some other developing economies, notably Indonesia, also made striking progress.

Figure 1

It is true recently the economic performance in the previously rapidly growing economies of Brazil and Russia has fallen significantly – in 2007-2017 Brazil’s annual average increase in per capita GDP was 0.6 percent and Russia’s 1.1 percent. But China and India are economically dominant within BRICS – accounting for approximately 80 percent of their GDP at both current exchange rates and PPPs. China and India’s rapid growth therefore ensures the economic dynamism of BRICS.

BRICS Common Interests

Turning to BRICS common interests, it is clear that the great benefits globalization brought to their economies make them opponents of protectionism – thereby creating common interests with the EU and Japan.

Geopolitically, BRICS have a joint interest in pursuing growth – which requires stability. This is why, for example, claims by some Western media that there would be major clashes between China and India turned out to be entirely inaccurate. When a border dispute between the two countries occurred at Donglang (Doklam), far from this leading to escalating tensions, both countries’ heads of government took decisive measures to defuse the situation. Similarly, replacement of Dilma Rousseff’s left-wing government in Brazil by the right wing one of Michel Temer led to no decrease in Brazil’s involvement in BRICS.

Development in Africa

So far, the situation of the final country in BRICS, South Africa, has not been analyzed. This is because South Africa has a specific position within BRICS. South Africa’s 57 million population is far smaller than China’s 1.4 billion, India’s 1.3 billion, Brazil’s 209 million, or Russia’s 144 million. Its economy is substantially smaller than other BRICS. South Africa’s inclusion is therefore not only for its own national economy but as a gateway to the African continent. Africa will, of course, play a key role at a summit held in Johannesburg and therefore it is worth examining Africa’s relation to BRICS’ development strategies.

Globalization is providing a framework for Africa’s development. In the last five years several African economies are among the world’s most rapidly growing – led by Ethiopia’s 9.9 percent annual average GDP growth, Cote d’Ivoire’s 8.6 percent, Tanzania’s 6.8 percent, and Rwanda’s 6.6 percent

Ethiopia provides a particularly spectacular example – with a population of more than 100 million maintaining an annual average 10.1 percent growth for the last decade. China, a key BRICS member, has played a “win-win” role in Ethiopia’s development both theoretically and practically.

Theoretically Ethiopia’s development model overall followed the path of “New Structural Economics,” developed by China’s former Vice President of the World Bank, Justin Yifu Lin. This sees development as transition from labor intensive to capital intensive growth. A country should base its strategy on its comparative advantage at any stage of development and then, with successful growth on that basis, move to higher stages of more capital-intensive development. As Ethiopia started at a very low development level, as exists in most of Africa, it correctly focused on labor intensive industries.

China also played a win-win role practically. In 2010 Ethiopia’s first industrial park opened in the town of Dukem built with Chinese investment. The major Chinese shoemaker Huajian, which produces for brands like Calvin Klein and Nina, set up its first factory in 2011 – initial investment was less than $5 million with 600 workers. Due to rapid export success the factory quickly expanded to 2,000 workers. Huajian opened a second factory building on that success and created a further 4,000 jobs. The company selects 500 Ethiopian employees for six months to two years management training in China.

Production has reached 5 million pairs of shoes, gaining Ethiopia over US$31 million in foreign exchange earnings in 2017. Companies from Turkey, Taiwan Province of China and Bangladesh then followed Hujian’s investment.

Ethiopia aims to construct 15 industrial parks by mid-2018. To provide infrastructure, China built and financed a $4.2 billion Ethiopia-Djibouti electrified railway. Other African countries, such as Rwanda, are moving towards similar policies to emulate Ethiopia’s success.

As Lin noted: “The quick success of Huajian Shoe Factory in Ethiopia shows that the (Chinese) recipe can also work in other developing countries.” In more general terms: “Ethiopia and Rwanda are landlocked countries with poor infrastructure. If they can take advantage of their labor-rich advantages, develop labor-intensive light industrial manufacturing, and market their products to global markets, then other African and developing countries with a similar approach can develop and achieve success.”

But success by particular BRICS companies depends on maintaining a global economic framework – if globalization collapsed amid protectionism countries could no longer sell into the world market using their comparative advantage.

For this reason, BRICS, and other developing countries, have a powerful interest in maintaining the global framework established by the WTO and opposing moves to protectionism. This provides a further common framework for BRICS. Last month the foreign ministers of BRICS criticized what they called a “new wave of protectionism.” Similar positions will doubtless figure at the Johannesburg summit.

Source: China.org.cn

John Ross, Senior Fellow, Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China Focus

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +