Bush to Biden: Two Decades of U.S. Failure in the Middle East

The strategic importance of this region determines that the U.S. will not really withdraw. The retrenchment will be a long-term process of trial and error, during which policy confusions, contradictions, repetitions, and so on, are inevitable.

After nearly 20 years in the shadows, Taliban forces once again took control of Kabul, capital of Afghanistan, on August 16. The rapid Taliban takeover and the withdrawal of U.S. troops from the country denoted the end of the Afghan War first launched by the George W. Bush administration in 2001. Furthermore, it indicated the failure of U.S. policy in the Greater Middle East region, leaving the local geopolitical structure facing a new round of profound adjustments.

Focal shifts

The September 11 terrorist attacks on the U.S. in 2001 were a major turning point for America’s Middle East policy.

From the viewpoint of the Bush administration, the Middle East had to be fundamentally transformed so that the breeding ground of terrorism and extremism could be eradicated once and for all. “The war on terror” and “the export of democracy by force” became the two founding U.S. pillars to reshape the regional order.

Militarily, the U.S. launched its wars in Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003. However, the so-called “war on terror” backfired, harming the interests of both the U.S. and its allies in the Middle East. Afghanistan and Iraq were thrown into turmoil and went on to become the training camps and export sources for international terrorism.

Moreover, the “democratic transformation” carried out by the U.S. was dislocated from the national, social and cultural conditions of the regional countries. Worse still, radical Islamic forces in the region have since arisen, taking advantage of U.S.-instigated chaos.

After assuming the presidency in January 2009, Barack Obama proposed to end the global war on terrorism and transfer the U.S. focus to cope with the rise of China.

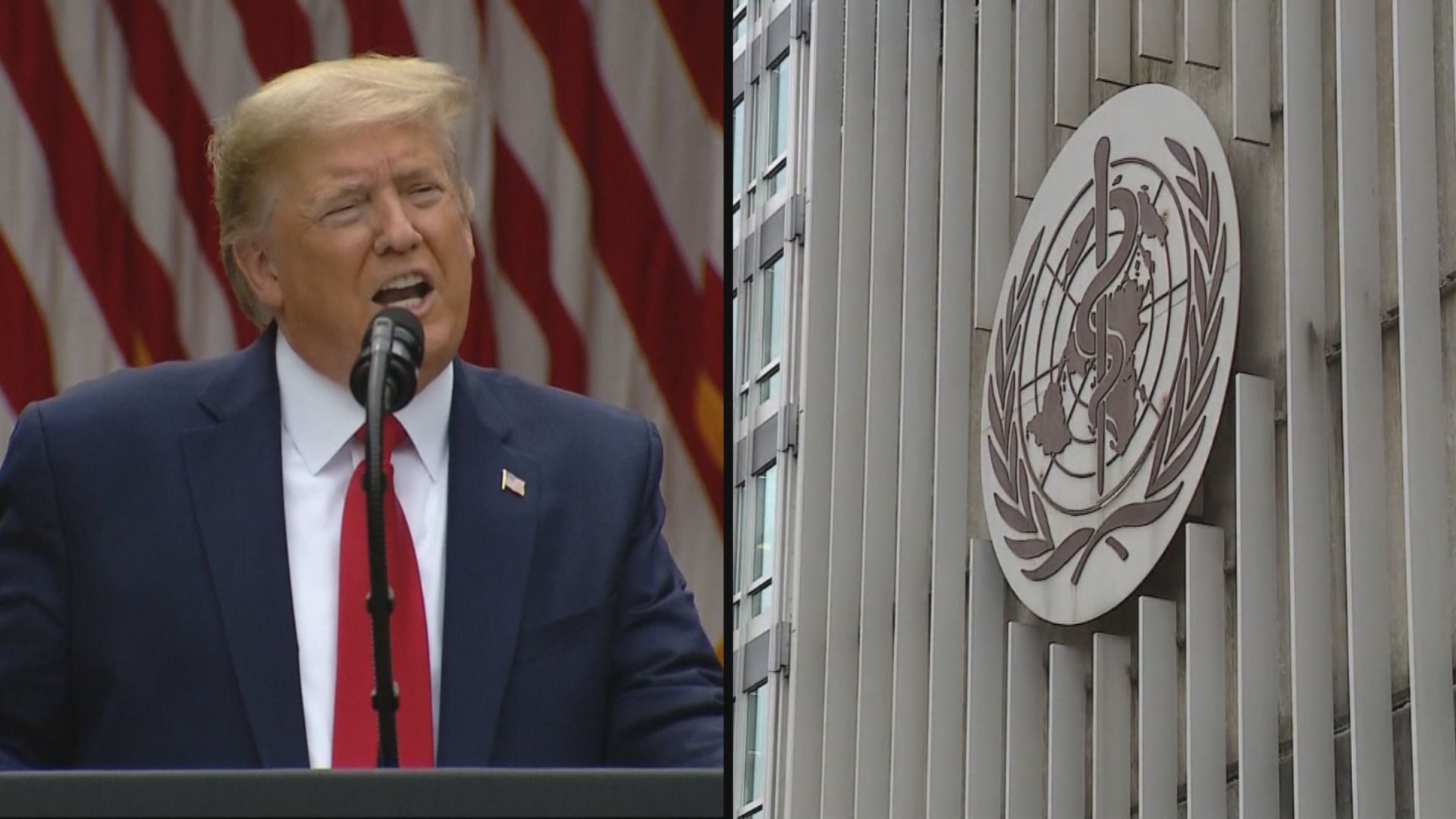

The Donald Trump administration (2017-21) continued to reduce U.S. involvement in the Middle East, shifting the core objective to one that would “keep the Israelis and Saudis up, the Iranians down and the Russians out.”

Biden’s priorities

Since taking office, President Joe Biden and his foreign policy team have been busy in the Middle East affairs, with a dizzying array of moves outlining the basic objectives of America’s strategy in the region.

The Biden administration hopes to strike a new nuclear deal with Iran to replace the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) signed between Iran, the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (China, the U.S., Britain, France and Russia), Germany and the EU in 2015. Biden and his administration believe that once the nuclear issue is settled, the “big conundrums” regarding Iran’s regional behavior, missile program and economic development will be swiftly solved.

In addition to reshaping America’s alliances in the Middle East through “value-oriented diplomacy,” the administration also seeks to speed up its disengagement from various wars in order to turn the “quicksand of war” into a “useful puzzle piece.” The pullout of U.S. troops from Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as the withdrawal of U.S. military support from places like Yemen and Syria, is expected to further try and turn those “negative assets of warfare” dragging down the U.S. into a “diplomatic positive energy” that may leverage the regional situation and serve U.S. interests in the future.

Finally, Biden wants to get some diplomatic bonus points by mediating the Israeli-Palestinian issue. Through reviving U.S. financial aid to Palestine, he intends to mobilize regional allies to pay more bills for the U.S. in its “management” of the Palestinians.

Despite its idealized visions, the current realities show that it will definitely not be easy for the Biden administration to either leave the Middle East or render the region manageable.

Challenges going forward

The Biden administration faces at least four major challenges to its Middle East policy.

The “Kabul rout” has driven regional allies’ trust in the U.S. to an all-time low. The Biden administration is trying to assemble “big investments” from allies in order to fill the gaping holes left behind by America’s walking away. Nevertheless, the messy withdrawal from Afghanistan makes it difficult for Biden to convince regional allies and partners that the U.S. has the ability and concern to guarantee their security plus economic and diplomatic interests while reducing its engagement in the Middle East.

Meanwhile, Arab allies are not buying into the so-called diplomacy. Even to this day, the hearts of many an Arab country still quiver with fears about the Obama administration’s intervention in the Arab Spring movement in the early 2010s. Today, Biden’s diplomacy is welcomed with a frosty, even hateful at times, reception. The turning of the cold shoulder, generally on the part of Arab leaders, comes courtesy of a diminishing U.S. appeal to its allies as the latter are wary of America’s potential ideological infiltration.

The prospect of resolving the Iranian nuclear issue also remains shrouded in uncertainty. Domestically, the U.S. features no broad consensus regarding a return to the JCPOA. Technically, it is a complicated feat, even if political and diplomatic factors are put aside, for Biden to lift sanctions and especially the “poison pill provisions” on Iran imposed by Trump. Moreover, it is not only the security concerns of regional allies like Israel and Saudi Arabia that will prevent the U.S. from making concessions, nor will Iran’s hardline leadership, with new President Ebrahim Raisi as its representative, compromise with the U.S. easily.

Finally, the increase in proxy rivalries in the Middle East will slow down the pace of the U.S. withdrawal from the region. At present, the trend of “bloc confrontation” in the Middle East geopolitical competition rages on more frantically than ever as major regional powers and groups are utilizing multiple “proxies” and “agents” to contest the “intermediate zone,” consequently intensifying fragmentation of the regional security pattern. This situation may make it more difficult for the U.S. to control its regional allies as the solidarity of the “modular alliances” that the Biden administration intends to create may be destroyed due to the endless emergence of organizations and proxies within them. Furthermore, it may also produce the perfect settings for the breeding and expansion of terrorist and extremist forces, leading the U.S. to face a new Middle East counterterrorism task.

Over the past 10 years, “strategic retrenchment” has become the main axis of the U.S. Middle East policy. However, it still has many regional interests that are hard to give up and many challenges that are difficult to deal with. The strategic importance of this region determines that the U.S. will not really withdraw. The retrenchment will be a long-term process of trial and error, during which policy confusions, contradictions, repetitions, and so on, are inevitable.

Liu Chang is an assistant research fellow with the Department for Developing Countries Studies at the China Institute of International Studies.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +