China and Japan have a thousand reasons to strengthen cooperation

How should we view the continuous improvement and development of Sino-Japanese relations? How should we understand the two countries’ positive roles in the current international landscape?

On the eve of the 2019 Chinese New Year, Japan held a lighting ceremony of the Tokyo Tower to celebrate the Chinese Lunar New Year. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe delivered a New Year speech, noting the Sino-Japanese relations have entered a “new era”.

China and Japan will participate in a series of important bilateral, multilateral and global diplomatic events such as the G20 Summit, and the China-Japan-South Korea leaders’ meeting in the several months to come.

How should we view the continuous improvement and development of Sino-Japanese relations? How should we understand the two countries’ positive roles in the current international landscape? How should the two countries strengthen cooperation to make greater contributions to regional and global peace and development? Those questions are worth reviewing and pondering under the framework of the changing world.

China-Japan Relations Version 4.0

Along with changes of production modes, civilizational forms, world landscapes, and international systems throughout history, China-Japan relations have undergone four “versions”:

Version 1.0 refers to the agrarian society before modern times, when China played an absolutely leading role in East Asia’s international system with its overwhelming national strength and cultural advantage and kept a dominant position in its bilateral relations with Japan.

Version 2.0 refers to the industrial society in the early stage of modern times. After a series of reforms, notably the Meiji Restoration, Japan “leaped from Asia to Europe” in terms of culture, and caught up with and even overtook China in national strength, which enabled it to gain the advantage in Sino-Japanese ties. In this period of nearly a century, Japan attempted to establish itself the leader of Asia through building the so-called “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” And launched an aggressive war against China. This attempt eventually failed as Japan was defeated in World War II and was incorporated into the U.S.-led Western Camp in 1945.

Version 3.0 refers to the industrial society and information society that continued to develop after the end of World War II. In the early 1970s, as a Standing Member of UN Security Council, China prevailed in world politics over Japan, and Japan prevailed over China economically, as it turned into the second largest economy in the world. China and Japan emerged as two paralleled powers.

Version 4.0 refers to the current intelligent society based on the industrial and information society. Facing both challenges and opportunities, difficulties and hopes, China and Japan are also part of the tremendously changing world landscape.

In the past decade, due to complicated changes in the external environment and intensive mutual collisions and frictions, both countries have realized that in the future they should move towards mutual complementation and harmonious coexistence.

Three Dimensions of New-type China-Japan Cooperation

The first dimension is regional development. As the world’s second and third largest economies, the development of China and Japan is rooted in Asia. Asia, as well as Eurasia that is geographically connected to Asia, will provide a broad space for the development of both countries in the future.

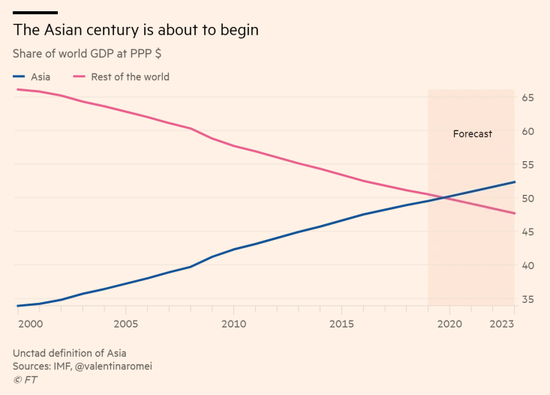

Starting in the 1950s, especially after the end of the Cold War, Japan, the Four Asian Tigers, China, Southeast Asia, and South Asia all saw rapid growth. The rise of Asia became a long-term structural phenomenon, instead of an occasional, periodical one.

According to the estimation of the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), by 2020, the total GDP of Asian economies will exceed the combined GDP of other economies in the world for the first time since the 19th century. Asia is home to half of the global population and middle-class groups. Of the world’s 30 largest cities, 21 are in Asia. The world is embracing an “Asian Century.” Considering that Asia had long dominated the world economy before the 19th century, this indicates that the world is resuming its historical normal state.

Resumption is not repetition. In the past, Asia was separated by geographical barriers such as mountains, deserts, oceans, and rivers, as well as political elements such as wars of aggression and anti-aggression, colonization, ideological divergence, and political alliances. Nowadays, after a long time of separation, Asia has been connected by highways, ports, airports, telecom networks and other facilities under the cooperative framework of the Belt and Road Initiative.

With the expansion of connectivity, the vast geographical space has been transformed into cooperation dividends, which integrate with demographic dividends to achieve a virtuous cycle between market exploration and investment growth. In the new round of globalization and informatization, negative factors such as underdevelopment, poverty, and terrorism are expected to be overcome, and Asia, which has generally lagged behind for a long time, will embrace a historic opportunity to become a developed continent. Furthermore, Asia is becoming more and more independent. Unlike previous Europe-oriented and U.S.-oriented trends, today’s Asia pays more attention to meeting its own needs and seeking self-innovation.

In the process of “Asianization of the world” and “Asianization of Asia,” China and Japan may join hands to play the leading role in Asia and further achieve their own improvement and upgrading while consolidating the social foundation for Asia’s connectivity and promoting regional integration through coordination and cooperation. This prospect will benefit not only China and Japan but also Asia at large.

The second dimension is technological innovation.

Since the second half of the 18th century, human society has gone through three industrial revolutions. At present, it is embracing the fourth industrial revolution featuring 5G, the Internet of Things and artificial intelligence (AI).

The fourth industrial revolution is an overall revolution. Apart from traditional economic activities such as production, sales, and consumption, it also involves a wide array of sectors including health, medical care, and public service, and influences the way of living and the future of mankind.

The third dimension is social governance. Currently, China-Japan cooperation in this field focuses on negative impacts of economic, social and technological development, and the two sides are working hard to promote balanced development between humans and nature and between humans and technology, as well as a balanced development of different countries and different peoples.

In the process, the two countries need to constantly communicate and keep dialogues with each other, explore spiritual resources from their shared Asian traditional culture, and creatively develop and transform them into Asian values that respond to the call of the times. For instance, in the face of trade protectionism, both countries advocate a free, open, inclusive and orderly international economic environment and a new type of equal, balanced global partnership for development, which is conducive to increasing the common benefits and interests of the whole mankind.

In addition, as leaders in the fourth industrial revolution, China and Japan have realized that technology is a “double-edged sword.” As we develop intelligent technology, countries around the world must carry out extensive cooperation to prevent intelligent technology from bringing destructive consequences to the development of human society.

Based on those general trends, China and Japan have a thousand reasons to strengthen cooperation, and not one reason to confront each other. In this new era, we hope the two countries will walk on a path of virtuous cooperation and development that is win-win, mutual beneficial and multi-win.

Jin Ying, Research fellow at the Institute of Japanese Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences

The article represents the author’s personal opinion which does not represent the China Focus’ stance.

Editors: Dong Lingyi, Li Gang

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +