China’s Principled Diplomacy Resonates with Central Asia

In essence, the SCO has existed to provide a multilateral means for managing complex relationships in Central Asia, significantly improving regional development and security.

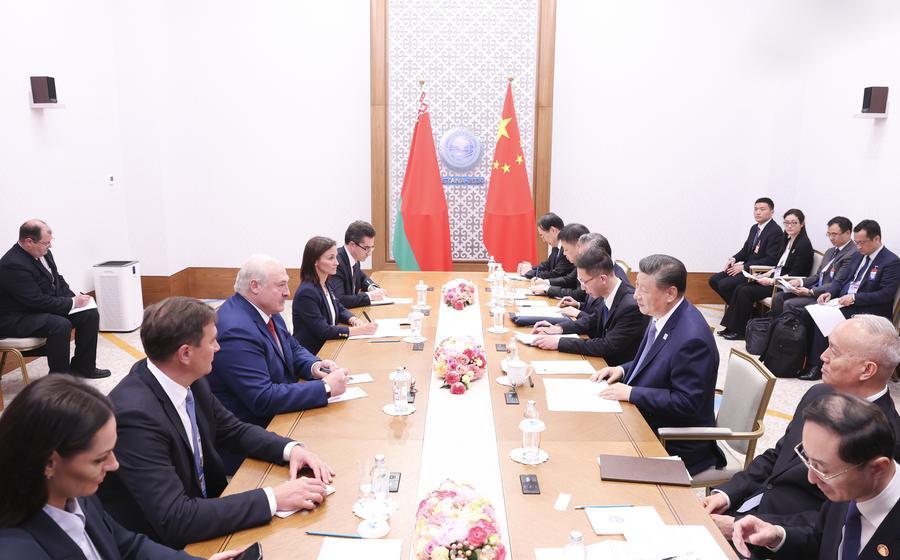

President Xi Jinping’s attendance at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) meeting in Astana, as well as his state visits to Kazakhstan and Tajikistan, show that China is strengthening both its bilateral and multilateral relations with Central Asian nations.

One of the most significant accomplishments of the trip was the continued reinforcement and expansion of the SCO. This organization has been instrumental in resisting hegemony and addressing security, development, and humanitarian concerns in Central Asia, particularly in the aftermath of the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan following 9/11.

Western thinkers have long promoted strategic paradigms that assert controlling Central Asia is key to global domination. Some of these paradigms view Xizang as a regional appendage, suggesting that whoever controls the highlands gains significant leverage over the rest of China. This is why, historically and presently, great powers have played strategic games to exert control over Central Asia and Xizang. Today, external forces continue to encourage separatism in Xizang and Xinjiang as part of a broader strategy to either dominate or destabilize these areas in a bid to contain China and limit Asian security and development overall.

When the U.S. entered Central Asia by force after 9/11 and built bases to project power in the region, it created unacceptable risks, particularly for China’s defense and space industries in its western regions. At the same time, China, increasingly capable of working productively with Russia and other regional partners, developed more desirable alternatives, including better security and development initiatives. These efforts saw major steps forward in the new era with the bold policy innovations associated with the Belt and Road Initiative and the development of major-country diplomacy.

The disastrous 20-year U.S. occupation not only devastated Afghanistan, but also, ironically, led to the return of the Taliban. In the 1980s, the U.S. supported Afghan Mujahideen fighters, some of whom later formed the Taliban, in their battle against the Soviets. Decades later, the U.S. found itself fighting the Taliban in the post-9/11 “War on Terror.” Then, when the U.S. abandoned Afghanistan a few years ago under fire from advancing Taliban forces, they left heavy weapons behind, effectively re-arming their former adversaries. Was this a deliberate attempt to sow seeds of turmoil after the U.S. control failed? The subsequent freezing of Afghan assets created more desperation in Kabul and the region overall. Perhaps, it’s fair to say American actions in Central Asia had long sought to create more turmoil in the region, and certainly in Xinjiang as well.

In this context, the SCO found its footing and genius. However, regional great powers also needed to balance their strategic interests in Central Asia. Central Asian countries sought to maintain their independence and avoid entanglement in complex power games. At the same time, it was in the interest of both major and minor powers in Asia to collectively find ways to achieve better balances, ensuring real security and development for all.

To a large extent, the SCO has provided a means to address the strategic vulnerabilities of the region that imperialist-minded opportunists have long exploited. One can argue that the critical element has been Beijing’s commitment to win-win solutions, advancing security alongside development, and following a principles-based foreign policy consistent with the tradition characterized by the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence.

It is worth noting that President Xi led commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the Five Principles this year and has consistently emphasized the importance of a principled approach to foreign affairs. This message has been especially welcomed in Central Asia and throughout the Global South, where historical exploitation and neglect are fresh in memory. Once stuck on the periphery, they are now becoming more connected to the new centers of an emerging multipolar world, largely due to Chinese leadership and material support.

I recently spoke with a Western Marxist who tends to idealize the old internationalism of the Soviet Union. He suggested that the SCO has a disadvantage relative to NATO because NATO countries are all (nominally at least) liberal democracies with relatively free economies. Therefore, despite their differences, they share the same fundamental ideology. Additionally, liberals have made a similar criticism of the BRICS, questioning why these countries work together despite having different values, political systems, and economies. Both criticisms betray a commitment to real diversity, regarding differences as fundamentally inconsistent with finding a broader common ground. In short, such criticisms suggest a totalitarian orientation, one that completely at odds with the vision of building an inclusive community with a shared future.

However, the SCO, BRICS, and other Chinese-led initiatives are not seeking to build a bloc to fight against NATO, like the former Warsaw Pact. Instead, their purpose is to avoid a reductive win-lose paradigm, to work together despite differences, and to create real opportunities for peace and development rather than surrendering to an endless cycle of crises and conflict. This approach is essential for regions like Central Asia and Asia as a whole to move forward, given the tremendous diversity of the world’s largest and most populous landmass. The same is true for the broader Global South.

Many Western mainstream narratives assert that Russia and China, both being SCO members, are in lockstep with each other, or more dramatically, as the president of Finland recently asserted, that China has so much leverage over Russia now that President Xi could end the conflict in Ukraine with a phone call to President Putin. Some argue that China is, therefore, responsible for the conflict in Ukraine, that China is providing lethal assistance, and that China is a danger to Europe as it supports alleged Russian imperialism. Nonsense.

Russia and China have significant differences between them—all countries do—but Beijing and Moscow recognize the need for strategic cooperation to minimize conflict and competition, especially in a world that faces challenges unseen in a century. How Russia deals with such challenges on its Western border is up to Russia, Ukraine and the Western powers waging a proxy war there. China continues to remain neutral and empathizes with both sides, and has made concerted efforts to encourage a return to peace. The example of Ukraine unfortunately provides a powerful counterpoint to what’s happening in Central Asia, where such risks have been mitigated through improved cooperation given the success of the SCO. Indeed, one might say that the SCO is a paragon of emphasizing cooperation over competition without regressing toward assimilation or universalism—a model that should be emulated by others around the world who emphasize “or” over “and” (和). Such authentic inclusiveness is precisely what the SCO and President Xi’s Global Civilization Initiative exemplify.

What is SCO? It is an organization founded on the basis of the Shanghai Spirit, which features mutual trust, mutual benefit, equality, consultation, respect for diverse civilizations, and pursuit of common development. These six elements very well represent the direction of future international relations, and resonate strongly with the Global South countries. At the recent Astana summit, President Xi mentioned the Shanghai Spirit three times during his statement, in which he called for SCO members to build a common home of peace and tranquility, of prosperity and development, of good-neighborliness and friendship, and of fairness and justice. His call was met with positive reception from participating leaders and beyond.

In essence, the SCO has existed to provide a multilateral means for managing complex relationships in Central Asia, significantly improving regional development and security.

Finally, we saw President Xi being welcomed during his state visits in Kazakhstan, with whom China already has strong relations, and in Tajikistan, where bilateral ties continue to strengthen. China and Tajikistan already have a comprehensive strategic partnership, but President Xi proposed further upgrading the partnership to better reflect the emergent needs of the new era. This includes deepening trade ties and promoting more synergies in national development strategies, especially through high-quality Belt and Road projects.

These bilateral advances, along with the SCO meeting and China’s support for other efforts, including BRICS and the first China-Central Asia Summit held in Xi’an last year, provide a comprehensive view of how Central Asia has emerged in the new era as much more than simply the geographical center of Asia, or the target of imperial whims. Once described as the graveyard of empires, Central Asia is now emerging as a region where empires are unnecessary and unwelcome, where common ground is emphasized, and where differences are managed, if not fully resolved.

All such efforts contribute to building a global community of shared future, an initiative representing the Chinese vision for world peace and development, personally launched by President Xi. The building of China-Central Asia community with a shared future, as announced at a virtual summit in 2022, is part of the bigger picture. The fruits of these efforts will be among the Chinese leader’s most enduring legacies for human development and security.

Josef Gregory Mahoney is a professor of politics and international relations at East China Normal University and a senior research fellow with the Institute for the Development of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics at Southeast University and the Hainan CGE Peace Development Foundation.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +