Convergence over AI Governance Amid Differences

Amidst various major international initiatives and frameworks on AI governance, it is essential to establish and nurture communication channels among these different international efforts.

This year marks a significant year for establishing guardrails around artificial intelligence (AI), with major regions like the EU, the U.S., and China, converging over a risk-based regulatory approach, albeit with distinct differences. This trend reflects a broader trend towards digital sovereignty, with governments seeking increased control over their digital markets and technologies to ensure safety and security, while aiming to boost their AI competitiveness. The pursuit of digital sovereignty, while both necessary and legitimate, carries the risk of erecting new barriers. This requires global efforts to strike a balance between maintaining control and fostering collaboration and openness.

From a regulatory standpoint, the EU is at the forefront with its AI Act, which was confirmed by the European Parliament in March 2024, marking it as the first globally comprehensive AI legislation. The Act establishes a four-tiered risk framework that prohibits certain AI applications, enforces strict regulations and conformity assessments for high-risk uses, mandates transparency for limited-risk applications, and suggests guidelines for non-risky applications. Stringent obligations only apply to generative AI if categorized as a high-risk application. The Act exempts open-source models unless they are deployed in high-risk contexts. A new oversight mechanism is established, including two EU-level institutions: the AI Office and the AI Board, which are tasked with ensuring compliance and facilitating the development of codes of practice, yet without directly overstepping national supervisory authorities of the member states, which still need to be established.

While the Act is a landmark achievement, it remains controversial as internal critiques argue that this could stifle innovation and competition, others argue that strong guardrails spur innovation as they provide not only safety and security but also legal certainty. Besides, most applications are expected to be in the lowest category and will not face any mandatory obligations. However, the Act’s extraterritoriality clause, which means that the Act will govern both AI systems operating in the EU as well as foreign systems whose output enters the EU market, could like cause frictions especially with the U.S. as it is perceived as protectionist. This is the flipside of all new guardrails as represented by EU’s comprehensive landscape of privacy, cybersecurity, and digital markets regulations.

The United States, in contrast has taken a different approach. Rather than enacting a comprehensive, national law, the U.S. government promulgated a Presidential Executive Order on AI on October 30, 2023, encompassing a broad array of guidelines, recommendations, and specific actions. This strategy aligns with the U.S. precedent of not having federal laws in other pivotal areas like digital governance, including cybersecurity and privacy protection. Despite growing recognition of the need for a more comprehensive risk-based approach, bipartisan support in these areas remains elusive. While the absence of federal legislation introduces legal uncertainty, it also allows for flexibility and an issue-focused approach to AI safety and security, notably for high-risk applications such as dual-use foundation models.

The Executive Order is not only a set of targeted restrictions with sectoral policies, like in transportation and healthcare, but also about fostering AI talent, education, research, and innovation and thus enhancing the U.S.’ competitiveness. The competitive dimension is not part of the EU AI Act. Some argue that this is symptomatic for the EU’s regulatory focus and the U.S.’s liability-oriented and competition-driven approach. Nevertheless, security concerns are paramount, as evidenced by proposed mandates requiring U.S. cloud companies to vet and potentially limit foreign access to AI training data centers or with provisions ensuring government access to AI training and safety data. This strategy underscores a deliberate effort to protect U.S. interests amidst the dynamic AI domain and intense competition with China for global AI dominance. The U.S. strategy faces a significant drawback — the lack of legislative permanence. This precariousness means the new presidential election could easily revoke the Biden-Harris administration’s executive order, undermining its stability and long-term impact.

China is the next major country that will most likely promulgate a dedicated artificial intelligence law by 2025, a path that was already signaled in the government’s New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan from 2017. The plan proposed the initial establishment of AI laws and regulations, ethical norms, and policy systems, forming AI security assessment and control capabilities by 2025, and a more complete system of laws, regulations, ethics, and policies on AI by 2030. The 2030 objective indicates that AI governance is an ongoing pursuit. For now, the Chinese government follows an issue-focused approach regulating specific aspects of AI that are deemed most urgent. It’s a centralized approach that successively introduces a regulatory framework of provisions, interims measures and requirements designed to balance innovation and competitiveness with social stability and security.

On the regulatory side, over the past three years, China’s Cyberspace Administration and other departments have issued three key regulations explicitly to guide AI development and use, including the Internet Information Service Algorithm Recommendation Management Regulations passed in 2021; the Provisions on the Administration of Deep Synthesis of Internet-based Information Services issued in 2022; and the “Interim Measures for the Management of Generative Artificial Intelligence Services” in 2023. The legal discourse in China not only covers ethics, safety, and security, but also issues concerning AI liability, intellectual property, and commercial rights. These areas have ignited significant debate, especially in relation to China’s Civil Code in 2021, a pivotal legislation aimed at substantially enhancing the protection of a wide range of individual rights. Importantly, China’s legislators use public consultations and feedback mechanisms to find a suitable balance between safety and innovation. A case in point is the current consultation on the Basic Safety Requirements for Generative Artificial Intelligence Services (Draft for Feedback) issued in October 2023. On the latter side, to boost AI innovation and competitiveness, the government approved more than 40 AI models for public use since November 2023, including the large models from tech giants such as Baidu, Alibaba, and Bytedance.

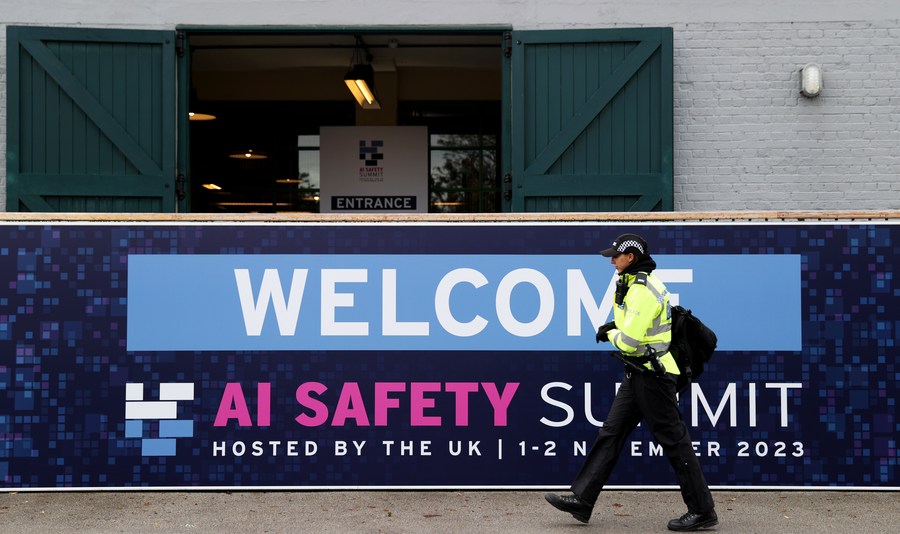

In parallel to those national measures, there has been a significant effort for forging AI collaboration on an international and multilateral level, given that no country or region alone can address the disruptions brought about by application of advanced and widespread AI in future. There are various frameworks that promote responsible AI, including the first global yet non-binding agreement on AI ethics – the Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence that was adopted by 193 UNESCO member countries in 2021. Also, for the first time AI safety was addressed by the UN Security Council in July 2023. Most recently, the United Nations Secretary-General’s AI Advisory Body released their Interim Report: Governing AI for Humanity. Its final version will be presented at the UN’s Summit of the Future in September 2024. High-level consensus was also reached on the level of the G20, which represents around 85 percent of global GDP, supporting the “principles for responsible stewardship of trustworthy AI,” which were drawn from the OECD AI principles and recommendations. Another significant step forward to bridging the divide between the Western world and the Global South was achieved during the U.K. AI Safety Summit. For the first time, in November 2023, the EU, U.S., and China and other countries jointly signed the Bletchley declaration pledging to collectively manage the risk from AI. Adding to this positive momentum, we have seen an AI dialogue initiated between China and the EU and China and the United States.

Despite such advancements, the lack of international collaboration remains, particularly with countries in the Global South. The exclusivity of the Global North is evident in initiatives like the G7’s Hiroshima AI Process Comprehensive Policy Framework and the Council of Europe’s efforts, which led to the agreement on the first international treaty on AI in March 2024. This convention, awaiting adoption by its 46 member countries, marks a significant step as it encompasses government and private sector cooperation, but predominantly promotes Western values. In response to the notable lack of international collaboration with the Global South, China has stepped up its efforts by unveiling the Global AI Governance Initiative already during the Third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing in October 2023. This move aims to promote a more inclusive global discourse on AI governance. At the annual two sessions of China’s top legislature and political advisory body in March 2024, Foreign Minister Wang Yi highlighted the significance of this initiative, underlining its three core principles: viewing AI as a force for good, ensuring safety, and promoting fairness. Amidst various major international initiatives and frameworks, it is essential to establish and nurture communication channels among these different international efforts. Those channels must aim to bridge differences and gradually reduce them over time. Developing governance interoperability frameworks could serve as a practical approach to address these differences.

Dr. Thorsten Jelinek is the Europe director and senior fellow of Taihe Institute. An active participant in several multilateral institutions, including UNIDO, OECD, G20/T20, and ITU, Dr. Jelinek holds visiting scholar positions at the Hertie School’s Centre for Digital Governance and University of Cambridge’s Department of Sociology. He also formerly worked as an associate director at the World Economic Forum.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +