Cryptococcal Meningitis, an Avoidable Tragedy

Scaling up antiretroviral therapy is by some way the most important means of improving the lives of people living with HIV (PLHIV) and addressing the AIDS epidemic, but it is not by itself enough.

Outsiders seldom get the attention they deserve. For example, a few favored species attract most of the available funding when it comes to conservation – the rhino overshadows riverine rabbit. In the arts, jazz and blues struggle to attract the attention given freely to pop music, and it’s rare to see a documentary, however deserving, surpass the success of an action film at the box office.

It can be difficult to pinpoint why this happens, but the phenomenon extends to diseases. A problematic and academic-sounding name does not help a disease gain widespread recognition. In addition, some conditions mainly affect people living in low and middle-income countries, leading pharmaceutical corporations to view them as unprofitable (often a misperception). As a result, money doesn’t flow into needed research and development for treatments, in turn hampering the engagement of the broader scientific community.

Cryptococcal meningitis, which fits all of the criteria above, is a notable disease outsider. Despite not making headlines, it is responsible for an estimated 180,000 deaths annually, mostly of people under 40 living in sub-Saharan Africa.

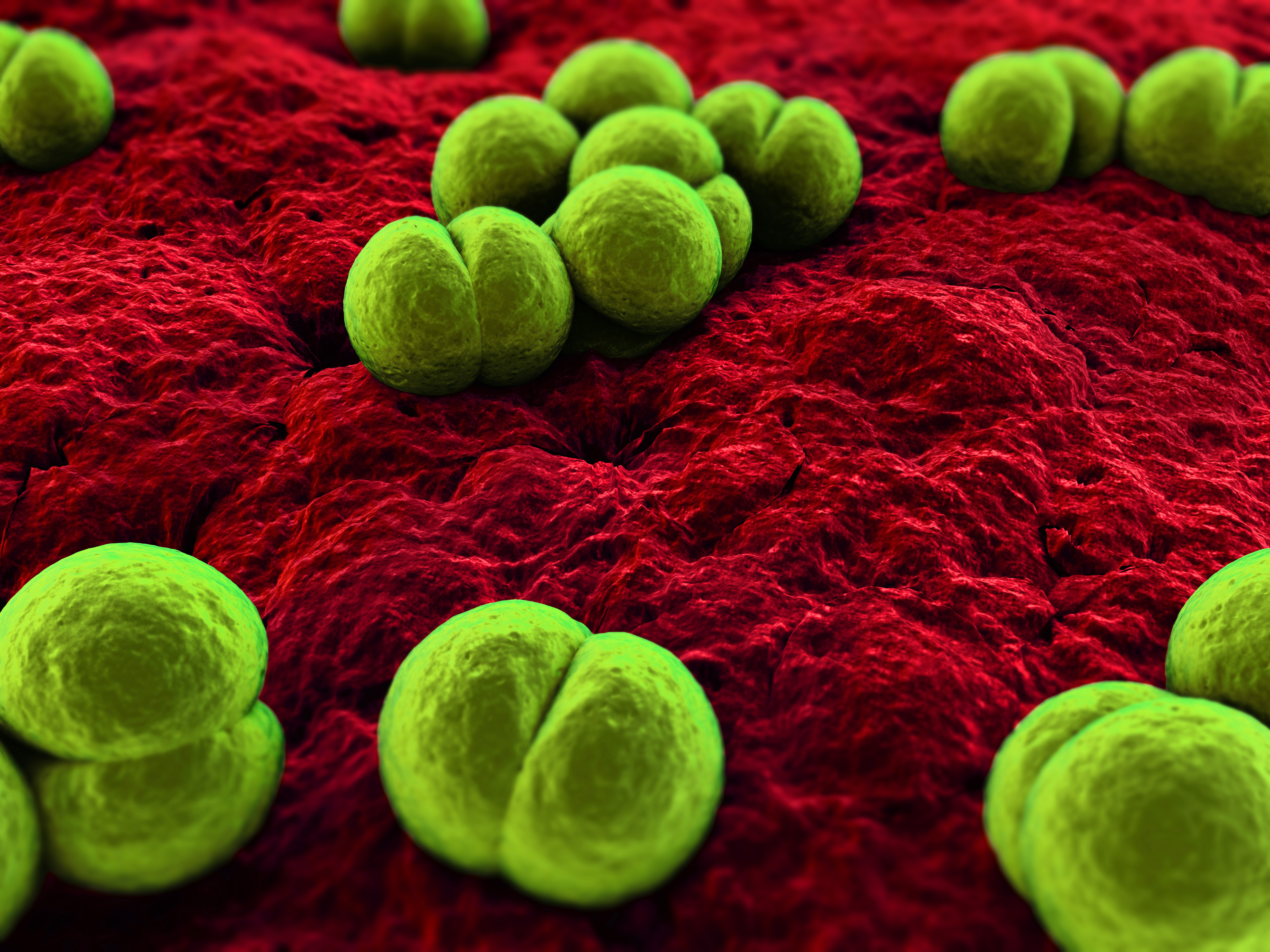

The causative agent, the cryptococcus, is everywhere in the environment. For those of us with a fully functional immune system, it causes no harm. However, in people with HIV who have severe immunosuppression, it can invade the brain’s lining, quickly leading to severe disease and death if left untreated.

This grim picture may lead you to think that cryptococcal meningitis is incurable, but this isn’t the case. In fact, with early diagnosis and optimal treatment, mortality could be reduced by over 70%. Achieving this at the population level would help avert hundreds of thousands of deaths between now and 2030.

This is far from the current reality, and it is a marker of the lack of recognition given to this disease that life-saving tools developed decades ago are still barely used today. For example, flucytosine – an essential drug for the treatment of cryptococcal meningitis – was developed in the 50s and is simple to make. Yet, most people with the disease today will never access it. There are many reasons for this lack of access: funding challenges, low clinical awareness, and a need for training. The other big reason why flucytosine is rarely used is that it is not registered in most countries where it is needed. On World AIDS Day 2021, it is time for governments to address that.

In South Africa, for example, while registration has been in process under the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) for almost two years, it has still not been finalized. Therefore, SAHPRA should urgently proceed to register this medicine. The government of South Africa has an opportunity to rapidly ensure all of its people who need it can access this life-saving medicine by quickly rolling out supplies and necessary support.

Cryptococcal meningitis and the bigger HIV picture

Scaling up antiretroviral therapy is by some way the most important means of improving the lives of people living with HIV (PLHIV) and addressing the AIDS epidemic, but it is not by itself enough. In 2019, there were still 690,000 deaths from HIV-related causes, including opportunistic infections like cryptococcal meningitis. Improving things on the treatment side of the equation could help address that.

In HIV care, a public health approach and quality care for the very sick have been pitched as mutually exclusive for too long. It is time to focus proportionate energy and investment on PLHIV who become ill with opportunistic infections, ensuring that they get the care they deserve.

What needs to change?

There is a global strategy to end tuberculosis, the biggest killer of PLHIV, but no plan to end cryptococcal meningitis, nor other significant causes of death of PLHIV.

UNAIDS and the WHO, the multilateral health organizations at the helm of the HIV response, can help by acknowledging the seriousness of the problem through steps that include measuring cryptococcal meningitis deaths, setting targets for reducing those deaths, and assisting countries to develop strategies for meeting those targets.

It is regrettable when an outsider doesn’t receive due recognition. But, in the case of cryptococcal meningitis, it’s an avoidable tragedy.

Amir Shroufi is a former MSF South Africa medical coordinator and current member of the MSF Southern Africa board of directors.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +