Demographic Doubt

Raising the fertility rate is no walk in the park. To address this tough challenge, China is working to develop and refine national strategic proposals, medium and long-term plans, and local policy deployment.

“A fertility-friendly society is taking shape in China,” said Yang Jinrui, deputy director of the Department of Population Surveillance and Family Development of China’s National Health Commission (NHC), at a January 20 press conference. It was NHC’s first 2022 press conference and focused on China’s population situation.

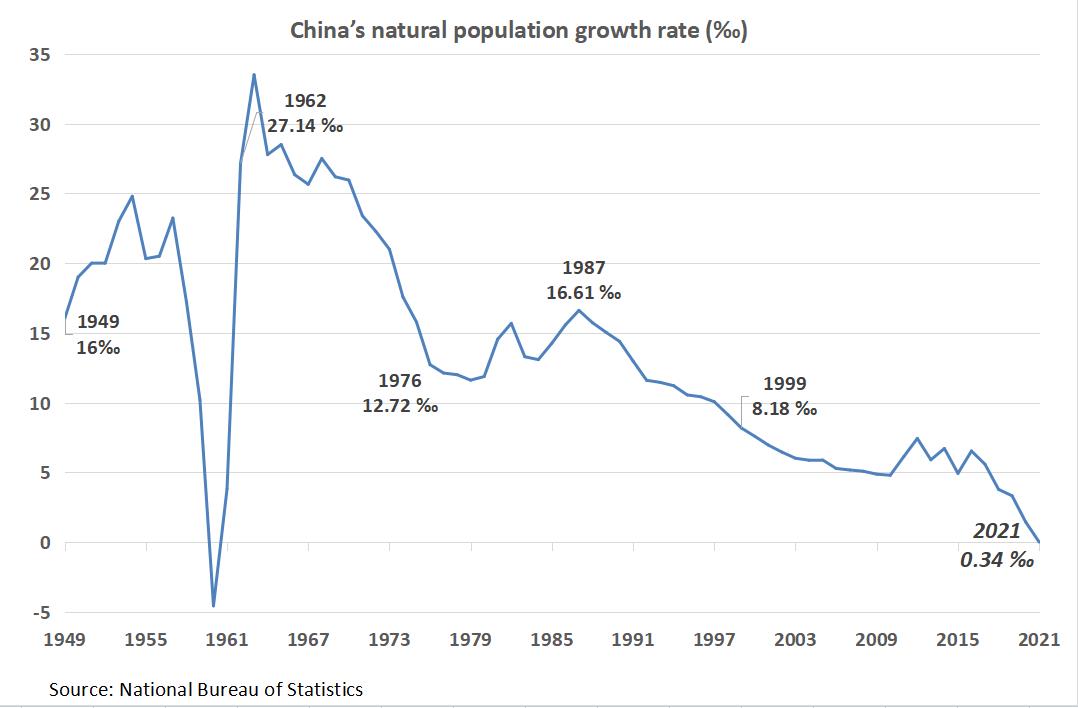

Earlier, on January 17, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) released the latest data on demographic trends: the population on the Chinese mainland had grown to 1.4126 billion by the end of 2021, an increase of 480,000 compared to the end of 2020. In 2021, births numbered 10.62 million, with a birth rate of 7.52 per thousand; the number of deaths was 10.14 million with a death rate of 7.18 per thousand, culminating in a natural growth rate of 0.34 per thousand. In terms of age structure, the population aged 65 and over was 200.56 million, a further increase compared to 2020.

Although the population continued to grow in 2021, the gap between the numbers of births and deaths is shrinking, according to the data. Some have suggested that China’s population could start declining after 2022.

Population peak

A survey of net population growth over the years since the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949 shows that the net population growth in 2021 was the lowest since 1962 and the first time the figure has fallen below 1 million excluding years of natural disasters.

NBS Director Ning Jizhe attributed the birth decline to multiple factors. “The slowdown in population growth occurred as a natural result of China’s economic development, especially in certain stages of industrialization and urbanization,” he said. “An aging population with fewer children is a common problem faced by many developed countries and even some emerging economies.”

According to Ning, three key factors led to fewer births in 2021: First, the number of women of childbearing age continued to decrease. Second, young people are less willing to bring a new life into the world because attitudes about having children have changed. Third, to some extent, some young people have delayed plans for having children because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

For the first time in decades, China’s birth rate fell below 10 per 1,000 people in 2020 (8.5 births per thousand), and in 2021, the figure plummeted to a new low, 7.52 per thousand. A continuation of this trend could mean that China’s population of 1.4126 billion has peaked and that net population growth in 2022 could be zero or negative.

Wang Guangzhou, a research fellow at the Institute of Population and Labor Economics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, opined that China could skip the “zero population growth” stage and directly enter an era of “negative growth.” Last year’s net population growth of 480,000 reflects the downward trend, according to Wang, but demographically speaking, negative growth is actually not the most pressing concern, whereas rapid negative growth, or ultra-low fertility rate, would be the real problem. “China’s fertility rate may reach an ultra-low level, which is not the same issue as the general sense of slow negative growth,” he noted.

Wang has data to support his theory. The results of the seventh national census show that in 2020 the average number of children born to women of childbearing age in China was 1.3, far short of the roughly 2.1 needed for replacement level, a figure that was last registered 30 years ago. “An insufficient number of births can hardly hedge against the number of deaths that remains at a high level of 10 million each year,” Wang illustrated.

“What’s worse, the number of women of childbearing age continues declining,” Wang said, citing data showing that 2021 saw a decrease of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) by 5 million over the previous year, including a 3 million decrease among women aged 21-35 in their prime reproductive years.

“There is also an imbalance between populations,” Wang added. According to China Statistical Yearbook 2021 released by the NBS, of all 494.16 million households nationwide in 2020, more than 125 million, or over 25 percent, were “one-person households,” close to 23.9 percent in South Korea, where the demographic situation is severe. Wang sees this trend as a signal of a shift to rapid negative population growth in China.

Negative growth alert

From the perspective of Yuan Xin, vice president of the China Population Association and professor of demography at the Population and Development Research Institute of the School of Economics, Nankai University, although a zero or even negative population growth would not severely impact the economy in the very near future given China’s massive 900 million working population compared to its 1.4 billion citizens, the population puzzle will still pose a daunting challenge to long-term economic growth.

Demographic changes will inevitably induce a great impact on economic and social development, said Li Jia, deputy director and senior researcher at the Aging Society Research Center of Pangu Think Tank, including massive reduction of the labor force, changes in the consumer market, and the impact on industrial production and service models.

The productivity, governance and management, and distribution mechanism cannot keep up when population surges. The same goes for accelerated negative population growth, which could create even more challenges.

“China’s current development plans such as investment in public resources and economic development plans were all mapped out on the premise of sustained population growth, so an opposite demographic trend will lead to a waste of public resources or inappropriate implementation of macro plans,” said Wang Guangzhou. In order to address the changes brought about by the new demographic situation, previous economic models and theories have to be updated, according to Li Jia.

Still, negative population growth is not just a matter of scale, but also of structure. Data released on January 17 showed that China’s population aged 65 and above had reached 200.56 million, accounting for 14.2 percent of the country’s total population, a new high. According to the international standards for defining an aging society, China has become a moderately aging society with a rapidly aging population.

“This means that the social security net, including the support system and the elderly-care system, will experience greater pressure,” said Wang Guangzhou. In the support system, for example, overdrawn pension accounts are found in more and more provinces, led by Heilongjiang, which had a deficit of 55.72 billion yuan (US$8.76 billion) in 2018. In terms of the elderly-care system, elderly people on average need more than six months of human labor assistance in terminal care. “You will find that the cost of human resources becomes very high as a population drops rapidly, especially in China where the current 100 million only children will have to deal with such demand in their twilight years,” Wang explained.

The demographic situation varies from region to region, and the impact could further worsen the situation in regions with severe negative population growth.

Wang again looked at Heilongjiang as an example. The seventh national census conducted last year showed that the province’s total population dropped 16.87 percent from 2010, and the figure exceeded 20 percent in Heihe City. The population of Suihua City has dropped by 1.66 million over the past decade. “These census numbers are the result of both the low fertility rate and population flows to other parts of the country,” Wang said.

Recent data showed China’s migrant population in 2021 at 384.67 million, 8.85 million more than the previous year. “Migration is a transformer that can exacerbate or alleviate changes in local demographic structure,” said Li Jia. “For rural areas with a net outflow of population, senior care will be a major future problem.”

According to Wang Guangzhou, the flow of labor to cities with high levels of economic development in eastern and central-western regions complies with the law of population mobility, but it can exacerbate population decline, economic recession, urban shrinkage, and increased aging in outflow areas. “This can easily result in a cycle which, if the Matthew Effect holds, may hinder progress towards achieving common prosperity,” he said.

Balanced population growth

But China’s population is still growing. Ning Jizhe asserted that China’s population will remain above 1.4 billion for some time to come.

In Wang Guangzhou’s view, the focus should not be on the total population, because if the number of newborns remains fairly low while the total population does not decline or only declines slowly, it will create a highly problematic age stratification with too many senior citizens. “The working population will face a greater burden unless the working age and retirement age are adjusted, which, however, would obviously not be easily accepted by everyone,” Wang said.

Some experts agreed that a net population growth of 480,000 was probably already an all-time low, suggesting the looming negative growth is only a matter of time.

To tackle the demographic crisis, in June 2021, China issued Decision on Improving Birth Policies to Promote Long-term Balanced Population Growth, and the subsequent implementation of the “three-child” policy became a top-level design for optimizing population policy.

Further measures to support the three-child policy are in the works, but results could take a while. Earlier experience in countries such as Japan and South Korea indicated that raising the fertility rate is no walk in the park. To address this tough challenge, China is working to develop and refine national strategic proposals, medium and long-term plans, and local policy deployment.

So far, 25 provincial-level regions across the country have completed or started revision of their population and family planning regulations. New mothers can take additional maternity leave ranging from 30 days to 90 days in general, and the revised regulations also added stipulations about universal child care services and protection of one-child families’ rights. Zhejiang Province, for example, has launched an initiative to construct a childcare-friendly society as part of its efforts to build itself into a demonstration zone for common prosperity. The municipal government of Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, plans to invest 400 million yuan in the development of inclusive child care. The city of Panzhihua, Sichuan Province, is working to improve its maternity service system and exploring issuance of maternity allowances.

From the perspective of Li Jia, the shift to a three-child policy is only the beginning, not the central focus of the policy to boost the falling birth rate. Rather, focus should be on finding solutions to problems brought about by childbearing such as infant and toddler care, childbirth and parenting difficulties in a long life cycle, and safeguarding maternity rights for working women.

Addressing the public’s worries about whether the paid maternity leave on the agenda in so many provinces can be truly implemented, Song Jian, deputy director of the Population and Development Research Center of Renmin University of China, said that the key is establishing a mechanism to ensure the cost of maternity leave is shared by the state, the employer, and the family so that women’s incomes aren’t affected and female employment discrimination isn’t aggravated.

Considering the fact that the number of women of childbearing age who have had “two children” in China is less than 10 million, Li Jia estimates that mothers of three would barely reach 1 million. But if more single people are encouraged to get married and have children, the additional population could reach 100 million. So, it is important to pinpoint what young people need to consider parenthood.

“China’s population is decreasing at a pace faster than expected, so efforts to implement relevant policies and advance necessary research and studies should be accelerated,” said Li Jia. “And, it is vital to apply scientific approaches to decision-making and solve essential problems at the source.”

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +