Earth Day Climate Summit: Did Developed Nations Finally Step-Up?

Developed nations have long been responsible for the effects of climate change, with United States President Joe Biden calling for them to do more and “step-up”. But many are still failing to answer this call.

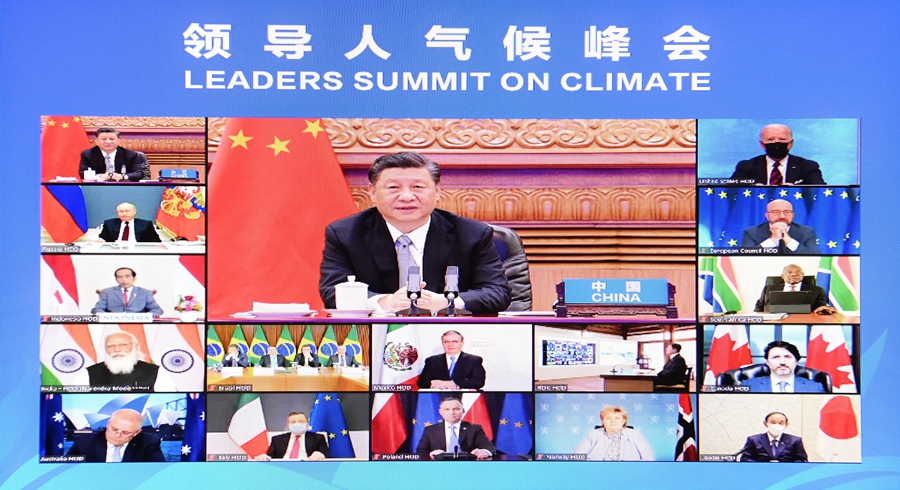

The Earth Day Climate Summit on April 22 was billed as one of the most important climate conferences in recent years, a chance for some of the world’s largest polluters to finally get on the same page before the decade-defining COP26 climate summit this November.

It was effectively a final dress-rehearsal before the delayed United Nations summit, and an opportunity for countries to explain how they would stop global temperatures from rising by more than 1.5 degrees Celsius, and ensure that the final curtain does not fall on the planet under their watch.

Leading the push was the United States – back from the environmental wilderness after four years of pushing zero action rather than zero emissions – with President Joseph Biden calling on the world’s richest and most developed countries to finally “step-up” and deal with the biggest existential crisis of our time.

Duty to do more

His admission for developed nations to indeed “step-up”, was a welcomed and long overdue motion. Too often developed nations have talked a good game on climate change; setting big targets and promising large amounts of money, without ever truly following through on them.

Targets to phase out fossil fuels for example have come as coal-power sees a resurgence in some developed nations, while aid packages like the $100 billion fund to help developing nations battle climate change, have never actually materialised.

And given the hugely disproportionate responsibility developed nations have over developing nations for causing climate change, it is only right these nations do more to control its effects.

Currently, developed nations make up six of the world’s top ten carbon emitters, with the US – the number two carbon emitter – producing 5.285 billion metric tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2019 – nearly five times the amount the entire continent of Africa emitted during the same period. Historically, they are also overwhelmingly more responsible for climate change, with 79 percent of all historical carbon emissions caused by rich nations, according to the Centre for Global Development.

Jennifer Morgan, Executive Director of Greenpeace International, highlighted this very point before the Earth-Day summit, stating: “The world’s richest countries must do more … having profited from extractive and polluting industries leading to the climate crisis. It’s time for the wealthiest nations to repair the damage and show solidarity with vulnerable countries.”

Real ambition?

On the face of it, countries seemed to have done their homework and answered Biden’s calls for action, with a raft of ambitious targets established that highlight a stronger commitment to tackling climate change.

The US announced plans to cut emissions 50-to-52 percent below 2005 levels by 2030, a significant improvement from its previous targets, while Japan and Canada also stepped-up their commitments to reduce emissions at a faster rate by 2030. South Korea, while not promising new 2030 goals, did promise to stop funding coal-fired power plants overseas, while both the EU and United Kingdom revealed significantly higher 2030 emission goals.

Only Australia and Russia failed to come to the party with any new ideas, and yet despite this, independent climate analysis organisation Climate Tracker have projected that these new targets – under the proviso that they are meet – will help cut the 2030 emissions gap by between 12-14 percent, the gap’s single biggest ever reduction.

Or business as usual?

Job done then? Not quite.

Despite greater ambition admittedly on show, there were many who left the virtual summit feeling that the proposals put forward by developed countries had not truly grasped the “once in a lifetime” opportunity they had been given.

Like many climate summits before it, criticism of their plans boiled down to two main sticking points; a lack of how they would achieve it, and where the money was coming from?

Funding for green projects in developing nations was by far the biggest example of this, with many developed nations simply failing to disclose how much they would give, or who the money would go to. Would it be in the form of free funds? Or would it be in the form of expensive loans with high repayments? These answers were left unanswered, perhaps on purpose.

To its credit, the US was one of the few countries that did produce figures, promising climate financing to developing nations worth $5.7 billion a year by 2024. But this figure was still less than the $6 billion 40 members of Biden’s own party had demanded earlier. It also contained no mention of extra funding for the Green Climate Fund, a fund which directly helps developing nations with funding infrastructure projects, and of which the US has failed to inject funds into for the last four years.

In terms of ambition, Australia and Russia’s decision to bring nothing to the table was a disaster, while Canada – the world’s tenth largest emitter – and South Korea’s proposals also fell into the category of uninspiring. It was startling that Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was announcing targets to cut domestic fossil fuel consumption, just as his government were tweeting about growing domestic oil and gas production in the country.

The US’ target for cutting emissions, while double its previous target, was also well under the 60-to-70 percent below 2005 levels by 2030 cuts that environmental groups such as Friends of the Earth had called for, cuts they say that would have signaled real intent and responsibility for their historical contributions. Instead, Biden will now oversee a target that effectively means US per capita emissions by 2030 will still be higher than that of EU today.

Where does this leave us?

With COP26 just over six-months away, time is running out for developed nations to harness their greater climate ambitions with even greater climate action.

Leaving developing nations to deal with this problem is not an option, and it is a damning inditement of Australia, South Korea and Russia’s environmental policies that their status at the summit was overshadowed by developing countries, such as China’s plans to bring its share of coal in total energy consumption to under 56 percent in 2021, and peak coal use by 2025.

Increased action will be made all the more difficult as their economies recover from COVID-19, with experts already forecasting carbon dioxide emissions to jump this year by the second biggest annual rise in history.

But given their current and historical carbon-footprint, and their unrivalled finances to deal with this problem, developed nations must “step-up” further to address the climate crisis, or risk the world drifting dangerously past the point of no return.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +