Elevating Heritage: Beijing Central Axis Joins UNESCO’s Prestigious List

UNESCO’s recognition of the Beijing Central Axis stands as a powerful symbol of the revival of a civilization.

Following the decision made at the 46th session of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Committee, the Beijing Central Axis has been added to the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites, bringing the total number to 1,223. With 59 sites now included, China ranks second in the world for the number of landmarks and areas protected by international convention administered by UNESCO, just after Italy. This programme began with the adoption of the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage by the General Conference of UNESCO in 1972. In 1987, the first six Chinese sites were inscribed on the prestigious list, including the Imperial Palaces of the Ming and Qing Dynasties in Beijing and Shenyang.

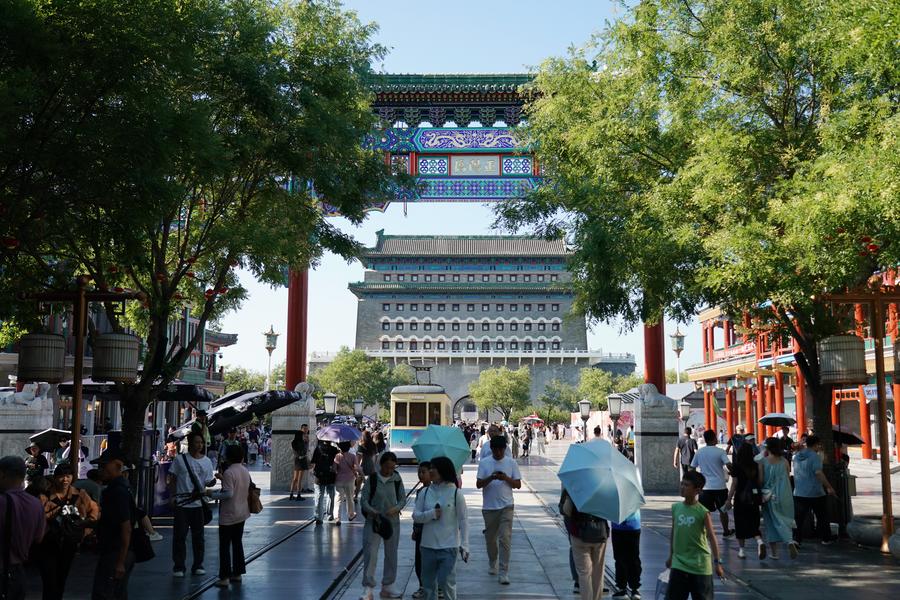

UNESCO has recognized not only a material heritage but also a concept, a vision of the world, and a view of the cosmos: the Beijing Central Axis, a building ensemble that exemplifies the ideal order of the Chinese capital. The axis extends 7.8 kilometers from the Drum and Bell Towers in the north to the Yongdingmen Gate in the south. As an element of comparison, the Avenue des Champs-Elysées in Paris is 1.9 kilometers long. Running north to south through the heart of historical Beijing, the Central Axis encompasses former imperial palaces and gardens, sacrificial structures, and ceremonial and public buildings. The most famous construction is the Forbidden City, the residence of 24 emperors during Ming and Qing Dynasties. The Forbidden City is a rectangle, measuring 961 meters from north to south and 753 meters from east to west. At the heart of the Forbidden City is the Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe Dian), the ceremonial center of imperial power.

Together, these elements testify to the city’s evolution and reflect the imperial dynastic system and urban planning traditions of China. The location, layout, urban pattern, roads, and design of the Central Axis illustrate the ideal capital city as described in the Kaogongji, an ancient text known as the Book of Diverse Crafts. The Kaogongji was part of the Rites of Zhou, included during the Han Dynasty (202 BC–220 AD).

The Central Axis originated during the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368), when the capital, Dadu, was established. It was during that time that Marco Polo (1254–1324) visited China and its capital. The axis also features later historical structures built during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) and refined during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

Any visitor to the Chinese capital quickly recognizes the significance of Chang’an Avenue. This major thoroughfare, in narrow sense, stretches from east to west, beginning at Dongdan in the east and terminating at Xidan in the west. The Central Axis runs perpendicular to Chang’an Avenue, intersecting it near Tian’anmen, which serves as the main entrance to the Forbidden City palace complex.

The UNESCO’s recognition of Beijing’s Central Axis will have an immediate and profound impact, significantly bolstering efforts to preserve the city’s architectural heritage. This designation underscores the global importance of the Central Axis, reinforcing the need to safeguard its historical and cultural value amidst rapid urbanization and modernization.

Balancing the demands of urban development with the imperative to protect cultural heritage is a complex challenge. The Central Axis, which runs through the heart of historical Beijing, is a testament to traditional Chinese urban planning and imperial history. Its preservation is crucial not only for maintaining the city’s historical character but also for honoring its cultural legacy.

The call for such preservation was notably advanced by Liang Sicheng (1901-1972), a prominent Chinese architect and historian. His father, Liang Qichao (1873-1929), was one of the most prominent Chinese scholars of the early 20th century. Immediately after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, Liang, along with other advocates, formulated what is known as the Liang-Chen Proposal. This proposal emphasized the importance of protecting the inner city’s historical structures against the backdrop of burgeoning modernization. Liang’s vision has laid the groundwork for contemporary preservation efforts, aligning with UNESCO’s recognition and reinforcing the commitment to maintaining Beijing’s unique architectural heritage.

The Beijing Central Axis offers another compelling reason to visit Beijing and explore its rich history. It serves not only as a historical landmark but also as an introduction to classical Chinese thought. Urban planning, after all, can be seen as a form of language that communicates deeper cultural and philosophical ideas. Classical urbanism reflects both a political order and a cosmology, taking a walk through Beijing a masterclass in Chinese philosophy. Visitors may find themselves at varying distances from the city’s center, but they cannot escape its significance.

Urban order is also important for inhabitants; it provides perspectives, orientation, and meaning to daily actions. In other words, it creates the conditions for social harmony.

The Beijing Central Axis embodies the connection between Heaven and Earth in imperial China. Moreover, the concept of centrality it includes is a cornerstone of Chinese philosophy and worldview. In my work, Limited Views on the Chinese Renaissance (2018), I delve into the importance of this notion within the Chinese context. The Central Axis stands as a vivid illustration of the preeminence of centrality in Chinese thought, reflecting its enduring influence on the country’s cultural and spatial organization.

The ongoing Chinese renaissance represents both a process of modernization and a reexamination of traditional Chinese culture. This dual approach signifies that, through its successful transformation, China is increasingly poised to shape global affairs. In this context, UNESCO’s recognition of the Beijing Central Axis stands as a powerful symbol of the revival of a civilization.

The article reflects the author’s opinions, and not necessarily the views of China Focus.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +