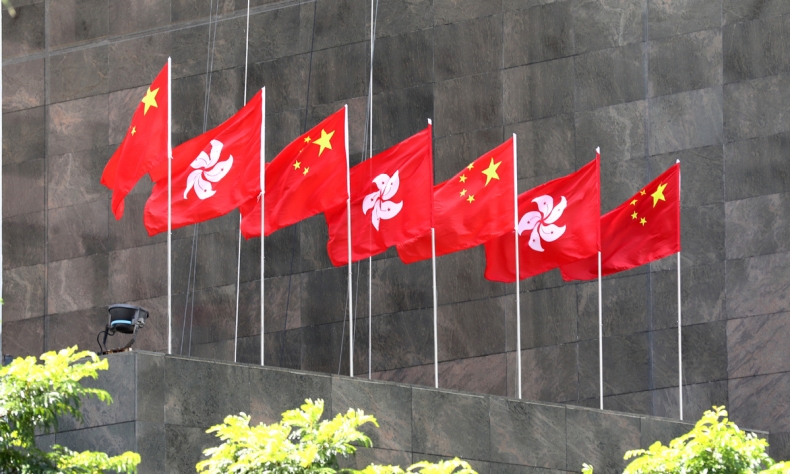

Fair and Orderly Election Establishes a Responsible Legislature in Hong Kong

The effectiveness of the Hong Kong SAR’s political system depends on whether it conforms to its real conditions, contributes to its long-term stability and improves the quality of life for all of its citizens.

The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) concluded its seventh election of the Legislative Council (LegCo) on December 20. Ninety elected lawmakers from a total of 153 candidates, with different backgrounds and across the political spectrum, make up the first legislature established since the region’s electoral system was improved in March. The election is considered momentous in the development of democracy with Hong Kong characteristics.

Under the Basic Law of the Hong Kong SAR, the main functions of the LegCo are to enact laws, examine and approve budgets, taxation and public expenditure, and monitor the work of the government. It also has the power to endorse the appointment and removal of the judges of the Court of Final Appeal and the chief judge of the High Court.

On the upgrade

The improved electoral model highlights fairness and competition. LegCo membership has increased from 70 to 90, with 40 returned by the Election Committee, 30 by functional constituencies, and 20 by geographical constituencies. All seats are contested and no one can be automatically elected, marking an unprecedented feat since the return of Hong Kong to the motherland in 1997. Conventional canvassing like visits to voters and promotional campaigns aside, the process witnessed 144 forums, giving candidates a stage to show themselves and further engage with the public.

According to a poll conducted by Hong Kong-based think tank the Bauhinia Institute, 36 percent of voters primarily focused on the candidates’ policy positions and proposals, followed by their campaign performance (29.3 percent), political experience (16.8 percent), political party background (10.8 percent) and public image (5.2 percent).

Representing different political groups and factions, candidates held different political ideas, some of which rather far removed from those of the current SAR government in the eyes of Hong Kong residents. Nevertheless, they got a shot at nomination, election even, under the principle of “patriots administering Hong Kong,” the final yea or nay resting with Hong Kong citizens.

The diversity among the newly elected legislators demonstrates the broad representation and political inclusiveness of the improved electoral system.

Take the 40 members elected by the Election Committee constituency, for example. Among them, there are experienced veterans who have previously served as LegCo members and a couple of new faces. Consisting of representatives of business, academia and the professions, as well as workers, employees and operators of small and medium-sized businesses from the primary level, they are expected to balance the overall interests of Hong Kong with those of different sectors and districts.

From a broader viewpoint, this LegCo election enables a group of highly capable patriots to participate in the administration of Hong Kong, with the council no longer acting as the stumbling block to local development and the catalyst behind a wrecked relationship between the Central Government and the SAR.

Poised to function more effectively, positive interactions between the LegCo and executive body can hopefully better realize policies to resolve deep-rooted social issues, improve the people’s livelihood and promote sustainable economic growth.

Rule Britannia

On December 20, denoting the big reveal of the LegCo results, China’s State Council Information Office issued a white paper entitled Hong Kong: Democratic Progress Under the Framework of One Country, Two Systems. This report reviews the history of the democratic system of the SAR and further clarifies Beijing’s position.

Though the UK claims that it has always been “supportive” of democracy in the region, the white paper clearly states there was no factual democracy in Hong Kong under British colonial rule. During its 150-year-long rule, Hong Kong was governed by a governor on behalf of Britain, answering only to the British Government and left entirely at its command. His paramount powers and prerogatives in Hong Kong were free of any checks and balances, and the governor could take charge of “all things belonging to his said office.” He further assumed all executive and legislative powers and possessed the authority to appoint and remove senior government officials and judges.

Local Chinese were long excluded from the governing bodies and were denied participation in Hong Kong’s management, with calls for democratic reform in the region repeatedly rejected by the UK.

Yet Britain suddenly reversed its previous opposition to “democratic reform” when it was left in no doubt about the Chinese Government’s determination to resume the exercise of sovereignty over Hong Kong. In October 1992, particularly, Chris Patten, the last British governor, imposed elements of a fake Western-style democracy in Hong Kong and rushed it through in the short remaining period of colonial rule, pretending to fight for democracy in the region. However, this move only intended to extend British political clout after Hong Kong’s return to China.

Making headway

Since Hong Kong’s return to China on July 1, 1997, much progress has been made in the region’s democratic system.

On December 11, 1996, a broadly representative Selection Committee, comprising 400 permanent residents from various social groups, sectors and backgrounds in Hong Kong, elected the first-term chief executive of the Hong Kong SAR. For the first time in its history, the head of Hong Kong was elected by its people, also demonstrating the first time a local Chinese citizen had assumed this significant role. Until 2021, four chief executive elections and seven LegCo elections have been held, with the lawful rights of all permanent residents in Hong Kong to vote and stand for election fully protected.

Chinese citizens who are permanent residents of the SAR can participate in the governance of both Hong Kong and the country as empowered by the law. For example, they can elect 36 deputies from Hong Kong to participate in the work of the National People’s Congress, China’s highest body of state power. More than 5,600 representatives from all across Hong Kong society serve as members of committees of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) at all levels, including over 200 on the CPPCC National Committee.

Nonetheless, Hong Kong’s local electoral structure remained heavily flawed. Politicians with ulterior motives could manipulate elections through loopholes in the system and enter the LegCo, paralyzing its operation and obstructing the administration of the government. With the escalation of U.S. containment against China, external anti-China forces were seemingly in cahoots with agitators in Hong Kong. With their support, these “activists,” under the guise of democracy, attempted to provoke a color revolution, eating away at the region’s stability and prosperity.

Democracy is not an ornament to be used for decoration; it is to be used to solve the problems that the people want to solve. The effectiveness of the Hong Kong SAR’s political system depends on whether it conforms to its real conditions, contributes to its long-term stability and improves the quality of life for all of its citizens. Today’s improved electoral system closes the loopholes plaguing the previous model and is a step forward in Hong Kong’s democratic development.

Promising prospects

Without any doubt, the Central Government will always support the Hong Kong SAR. Over the past year alone, it has issued a series of policies to benefit Hong Kong and its residents, covering trade, finance, culture, international exchanges and regional cooperation.

In order to address the land shortage problem facing Hong Kong’s development, the mainland has expanded the Qianhai Shenzhen-Hong Kong Modern Service Industry Cooperation Zone in Guangdong Province from 15 to 120 square km, in addition to facilitating financial, logistics, and IT activity between the mainland and SAR, effectively giving a strong push to Hong Kong’s efforts to diversify its economic structure.

Mainland cities in the Greater Bay Area are catering to Hong Kong youth in terms of policy, encouraging them to obtain a wider range of career development paths and entrepreneurial opportunities within their borders.

The Central Government is also particularly concerned about the Hong Kong residents living in divided flats and “cage homes,” determined to improve their housing conditions.

Today marks the dawn of a new era in Hong Kong.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +