How Should the US View the Communist Party of China?

China’s independence, and the efforts of other nations in the South to find their own independent ways, arduous as they are, ultimately are not compatible with Washington’s intensely ideological American-centric globalism.

Though I grew up in a Republican family in the Midwest, I became increasingly uneasy in the early 1960s about President Kennedy’s Vietnam policies and how they were so often justified in terms of an aggressive, expansionist China. Like other members of my generation, I came of age when it was increasingly hard to avoid seeing a wide-range of repellent American activities in Vietnam, the seemingly endless wars in Asia, misnamed nation building strategies and counter-insurgency methods, coups and regime change operations, covert wars. And all this amidst a burgeoning civil rights movement that sought to take steps to redresses America’s historic injustices at home. It was in this context that I began to focus on US policies towards China relations.

My study on China’s revolution

When I entered Harvard Graduate School in 1966, many students were mobilizing against what had become a full-scale war against Vietnam. But China was a far harder issue to deal with. None wanted a war with China; most spoke of “containment without isolation” as opposed to the “containment with isolation” policy that had largely dominated discussions since the Truman administration. But most saw China as a threat to “world order” and to the ways of the “modern” world they saw the US espousing and defending.

What struck me beneath all the different arguments and policy debates was Washington’s underlying hostility towards the PRC (People’s Republic of China) that colored almost all discussions, a hostility that was interwoven with an equally fierce idealizing of the US global role.

Then an odd twist of fate occurred that deeply affected my association with China. In 1966, President Kennedy’s family was instrumental in setting up what was then called Harvard’s Kennedy Institute of Politics. Given the tumultuous upheavals and ferment at Harvard among students in those years, it was decided that a young voice on China with radically different views should be asked to run one of the China seminars. So John Fairbank, the director of Chines studies, asked if I would run a China seminar.

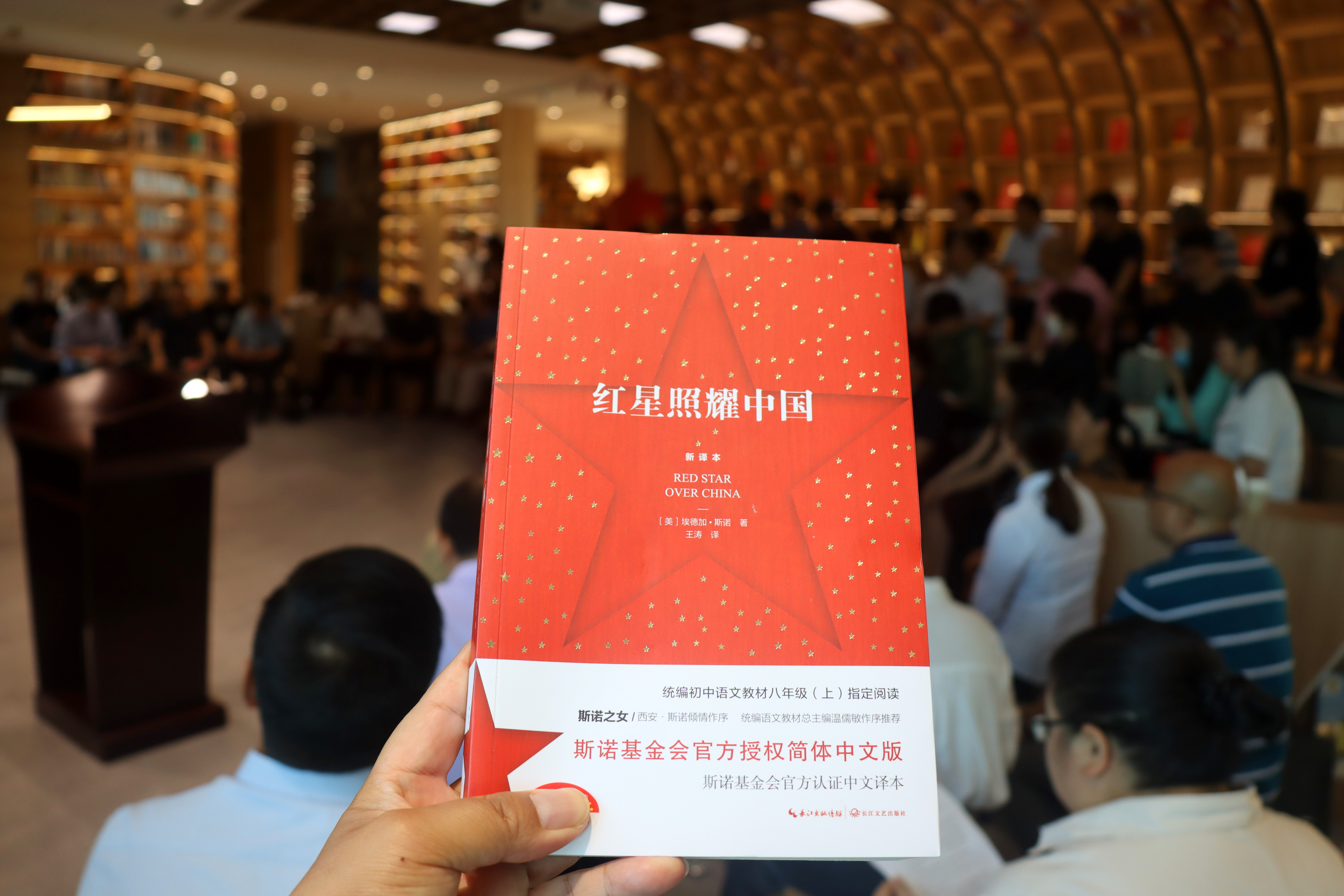

I decided to bring back Americans who had known China in the 1930s and 1940s whose careers had been scarred and blighted by Senator McCarthy and the anti-China hysteria of the 1950s. And in this way I came to know their writings and many of them personally – the diplomat John Service, the journalist Edgar Snow, the scholar Owen Lattimore, the writer William Hinton, and through them I came to know other old time China hands like Sol Adler, to name a few.

These were Americans by in large that, face-to-face with the most momentous revolution in history and often unsure of its implications, did not simply recoil then or thereafter. They had a kind of intuitive sense of how and why the Chinese Communist Party had come to lead this historic struggle and how and why it had come to embody China’s hope for a very different future. They felt deeply the ways Western powers and Japan had brutalized and humiliated China. Snow, Service, Adler and some of the others tended to see the Chinese revolution as a desperate attempt to rejuvenate and transform an entire civilization when so many other ways had failed. None ever forget the poverty and wretched conditions out of which the revolution grew; none lost their profound liking for the Chinese people they knew. They saw the revolution as a form of elemental justice. They felt the depths of China’s struggle for independence, for standing up, for finding its own way. And they approved.

They conveyed to me a sense of why the revolution was not something the US should contain or isolate. They hoped that the US government would somehow learn to live with the newly established People’s Republic of China. They had an acute awareness of the complicated and demanding tasks confronting China – and how American hostility and Washington’s policies designed to isolate a China that lived under constant nuclear threat, compounded the hardships and costs of China’s development after 1949.

Their sensibilities and insights about China, about its culture and civilization, about the role of the Communist party, about its quest to independently find its own way remain with me to this day.

Why can’t China be viewed objectively in the US?

The astonishing transformation of China – its economic prowess, its rapid urbanization without slum cities, its scientific and technological prowess, the education of its vast population, its modern infrastructure which is the envy of much of the world, and its continually evolving pattern of governance that has enabled these developments – has of course all taken place under the leadership of the Communist Party.

Yet I live in a country where the words “Communist Party” are largely thought stopping words. The unprecedented accomplishments that China made required the vision, skill, staying power, and constant transformation of the CPC (Communist Party of China) itself, its continual summing up of its experiences, and what polls suggest is popular support for the leadership of the Communist Party – little of this can be viewed objectively or approached with an open mind in the US.

Part of the problem, even among those open to a more accurate and sensitive understanding of China, lies in how the Chinese Communist Party is like no other political party in the world – and that its accomplishments are a reflection of this. As the Austrian philosopher Wittgenstein once said, the “limits of our language are the limits of our world.” Washington well understands that who rules the words often fashions what is seen and how it is judged. The effort to find different concepts, frameworks, key words, in China and elsewhere, to challenge those often limiting and imprisoning theories and words reflective of Western centrism remains a critical need.

Their absence in discussions in the US often precludes any understanding of why the CPC became central to the solution to China’s problems instead of standing in their way; why China has not adopted Western systems of governance, but sought its own; why and how the CPC evolved its developing patterns of governance out of a distinctive set of historical, revolutionary, and core aspects of Chinese civilization. And more: how the CPC has sustained national unity and stability today that enables a rapidity of prolonged change like no other nation has ever undergone.

All this contributes to making it difficult for Americans to understand what Service, Snow and others knew in their bones – how and why the Communist Party had come to embody the historic mission to lead China from some of its darkest days to a radically transformed, modern, socially more just society. There was no model, no blueprint for how to do this. But that’s another way of underlining how for over a century, amidst a constantly changing and threatening environment, the CPC found ways often through tumultuous struggles to remain a dynamic, experimenting, often highly pragmatic party capable in diverse circumstances of transforming itself while remaining true to its central vision.

US becomes increasingly hostile to China

America’s greatest existential threat today is not China; it is making China into America’s existential threat. The war of words launched by the US over the coronavirus is a sad commentary on the lack of needed cooperation, not to speak of a lack of compassion initially for the severity of the outbreak of the coronavirus in China in the early months. The escalating hostility towards China now so evident in Washington will all but ensure a competitive rather than any collaborative search for vital solutions. The result will be wasted resources, duplicative research, insufficient financing, and the undermining of international dissemination of advanced green technologies. And this is only to note the consequences for coping with just one of humanity’s looming crises.

Yet amidst all this, Washington has been gearing up for a full society mobilization against China – the “looming new superpower” that threatens America. In US national security discussions today, as well as in Congressional and media debates, the depiction of China as a frightening new superpower is in reality a reflection of what has so often happen in the past – a projection onto China of the dark underside of what American globalism has long been about. In the current frightening projection, China would, like the US, be everywhere and into everything. Its economic might will lead to a domineering Sino-centric world order; its military might would extend worldwide; its drones would be everywhere; its ethos would threaten alternatives of all sorts all over the globe.

But this is a fantasy, however useful for those lining up in Washington today for greater defense spending and those urging escalating military maneuvers against China. China, unlike Washington, will not have 800 overseas military bases, be invading and overthrowing numerous governments, or committing regime change actions throughout a large part of the planet as the U.S. has done for decades. Why? Because China is not the US – and the world is not what it was when US power sought to fashion an American-centric world after 1945. The world today is a very different place.

The world China entered as it embarked on its great reforms since the late 1970s coincided with a fundamental restructuring of the capitalist world as the US sought to reconstitute and transform the operations of its global centrality after the Vietnam war. The US was at home in a bipolar world; its global preeminence was augmented and ideologically sustained by it. China’s rise is a “rise” in a multipolar world, a very different world from the one in which the US envisioned a worldwide American-centric ordering of global capitalism amidst a “bipolar” struggle in the immediate post World War II decades.

Today, with China having become the world’s largest exporter; a financial powerhouse and global investor, a main trading power for a large number of nations throughout the world, its example of successful development and ways of governing itself, allows for in varied ways a greater range of choices for nations long locked into the embrace of “the West”. By becoming a major trading partner for Latin America, Africa, Saudi Arabia, and numerous other countries, China offers countries a range of alternatives to the US that profoundly encourages an increasingly multi-polar world. China’s growing power and wealth are reinforcing the opening up of choices, markets, bargaining room that did not exist nearly so intensively before for numerous non-Western nations.

The West’s comprehensive global dominance and its American-centric moment are slowly coming to a close as the non-Western world comes more to the fore. Washington is finding it has less control, less influence in such a world, whereas China may prove to be far more at home in it. It’s not that its immediate power is less, but its capacity to use it effectively and to control others has changed. What Washington’s preoccupation with China today significantly does is to filter these global changes through its depictions of a rising China rather than seeing China’s emergence as a part of this “rising” world. As a consequence, “China” becomes the problem, not more fundamentally the changing world the US finds itself in.

Even if China someday becomes the greatest power on the planet, as it well might, this is not about China somehow coming to dominate a growing number of determined independent nations and creating a Chinese centric world along the lines of a declining American- centric pattern. Indeed, China’s Belt and Road initiative, Washington’s attacks on it to the contrary, holds promise of being a dynamic step towards furthering a multi-polar order, not a new form of neo-colonialism. Laying the foundations for an interlocked pan-Eurasian economic cooperation zone that promises, however arduous the challenges, to further transform existing global economic and political dynamics.

What Washington still refuses to accept, as it has for seven decades, is that neither it nor any other power can dominate the world single-handedly. Not only is this about elemental realities of the limits of geopolitical power, it entails as well an acceptance that countries have to find their own ways to develop; that no model exists. And as China’s own quest to find viable and effective ways to develop shows, what brought China success came to be seen by Washington as clashing with its pre-eminence and its “rules”.

This globalist policy and the fervent conviction that the centrality of American power is indispensable for “world order” and the proper “rules based” functioning of the global economic system regrettably remains as strong as ever in President Biden’s administration. As before, it continues to profoundly distort the ability of Washington’s national security managers to accurately accept the world as it is today and China’s place in it. It makes Washington inclined to see aggressive drives that are in reality often reactive, defensive efforts to protect or project quite legitimate rights.

And more: this globalist strategizing repeatedly injects itself into a host of issues a wiser course would have sought to avoid – such as the extension of NATO to the East or the intricate and extensive involvement of the US in the South China sea and the various islands disputes. Rather than discussing the merits of the specific issues, Washington often weaves them into a complex, interactive dynamic of analysis and conviction so that global issues – the global big picture – overrides specific issues, making them all the harder to either resolve – or in the US context – to intelligently debate. Almost every time Washington’s “credibility’ is invoked, you’ll find this “big picture” descending into each specific issue in ways to muddy the waters. So much so that every time American credibility is invoked almost all sensible thinking and strategizing stops. The dangers in continuing down this road are obvious.

Let me summarize all this with a rather sweeping generalization. In Washington’s world an accurate image of China cannot easily emerge — and the reasons are analogous to why the US refuses to accept a multi-polar world. China’s independence, and the efforts of other nations in the South to find their own independent ways, arduous as they are, ultimately are not compatible with Washington’s intensely ideological American-centric globalism.

In the end, a view of China as part of an emerging multi-polar world, and not simply as an emerging superpower confronting Washington, provides a far more accurate context for understanding what has for so long been grossly distorted by America’s global agenda. In the future, there will be no superpower in the American model. The needed changes may be coming, but Washington continues to fiercely resist them. It would rather focus on China than the realities of the world it now confronts.

The world is diverse but not American-centric

In the long term, as I’ve suggested, the deeply rooted determination of the CPC to find an independent path for China has resulted and reinforced a genuine opening towards a more multi-polar, diverse world. It further opens up possibilities for many nations that tie in with China’s determination to create a more just society that can inherently reinforce how other nations understand their own struggles to find an appropriate path to develop. It suggests different ways countries can think about governing themselves.

This is inherently tied to developing far more effective means of global governance – and how and why respect for effective assertions of national independence is a central part of this. So much needs to be done; the vision is not sufficiently there. Global economic governance, reform of the global financial markets, and a model of fair and equitable governance reflective of the needs of the time – these are at their beginnings.

China brings to all this its own experiences – and the awareness that the historically oppressed nations, those still deep in poverty, those coping with waves of immigrates, have claims of justice that need to be a part of any viable vision of governance. But this is just to underline why developing concepts and visions of global governance need, as China has long insisted, to be opened up to the urgent needs and realities of the non-Western world.

If it is difficult to find the right words to understand China in the US on certain subjects, this is far less so in the non-Western world where China’s impact seems to me far more positively understood. Even in the US there is some awareness of the imperative necessity of finding new ways of governance –and thus a shared language may be easier here than in some other areas. This is a subject I hope to return to in later writings.

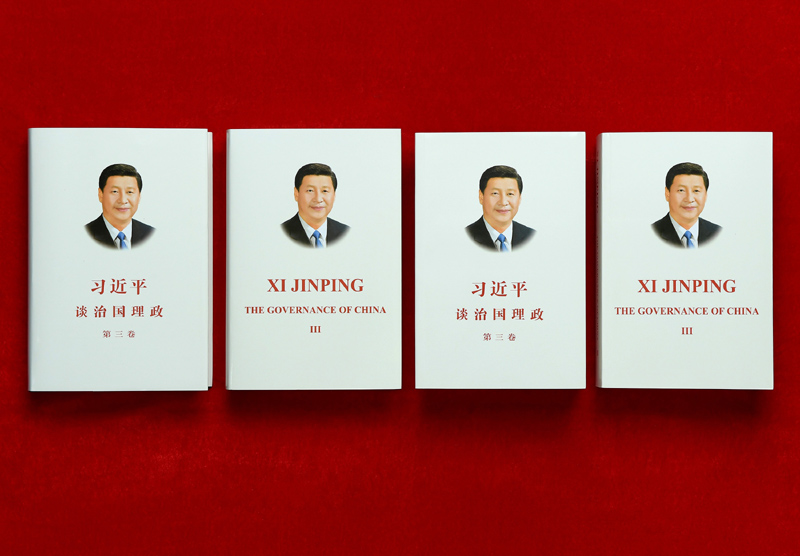

I’ve read President Xi Jinping’s three volumes of The Governance of China published by the Foreign Languages Press. I was struck by how he weaves together a commitment to the rejuvenation of China, core aspects of Chinese civilization, and a Chinese vision of socialism that is deeply rooted in the very origins of the CPC. His perspective on global problems is certainly wide ranging – including a deep commitment to an eco-civilization; the need to embrace and come to terms with the revolution of artificial intelligence; the call for new forms of global governance. It’s indeed rare to see a global leader so comfortably quoting from the diverse cultures of the world to develop his thoughts.

What this conveys to me is a conviction that while we may live in a globalizing world, this does not require a globalized, standardized, and homogenized vision of humanity. President Xi’s articulation of the Chinese Dream of national rejuvenation certainly speaks directly to this.

Here what emerges reflects what is perhaps most enigmatic in man’s historical experience – that we can speak of humanity but nowhere, in fact, can we convincingly discover a simplified, universal ethos. Humanity has played out its destiny in a diversity of languages, a multitude of moral experiences, and a considerable number of philosophies and religions. Humanity in this sense is irreducibly plural.

As President Xi says, “If world civilizations are reduced to one single color or one single model, the world will become monolithic and a dull place to live.” On the technical and scientific level, it is relatively easy to communicate; much about popular culture seems easily shared. Certainly, the problems we must somehow face together are frighteningly many. Yet on the deeper level of historical creation diverse civilizations need to communicate with each other with nuance and an appreciation that cultural differences are a constant source of enrichment for humanity. This is a far different and more enriching attitude than what one often finds among Americans who argue that it is the very decline of cultural distinctions that is the measure of the progress of civilization.

In the end, given its cultural density and enduing civilization, and a commitment not just to wealth and power, but to social justice, I came away from these books with a sense of why China may more easily encompass an appreciation of humanity’s variety than the homogenous globalization often seen central to Washington’s fading vision of an American-centric world. But America’s fading vision is not a sign of loss, as so many in the US believe. It is instead suggestive of the possibility, however small, that America, as it has sometimes been in the past, will be more “open” to the world as it actually is – and accept the coming place of China in it. And in that world, China will be the resurgent, if transformed and modernized civilization, that was long one of the greatest of all achievements of humanity.

James Peck is an Adjunct Professor at New York University in the History and the East Asian Studies Departments.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +