Identifying the Underlying Causes of Sino-U.S. Frictions

To treat China as a partner will do the U.S. and its people much more good than to look at China as a competitor.

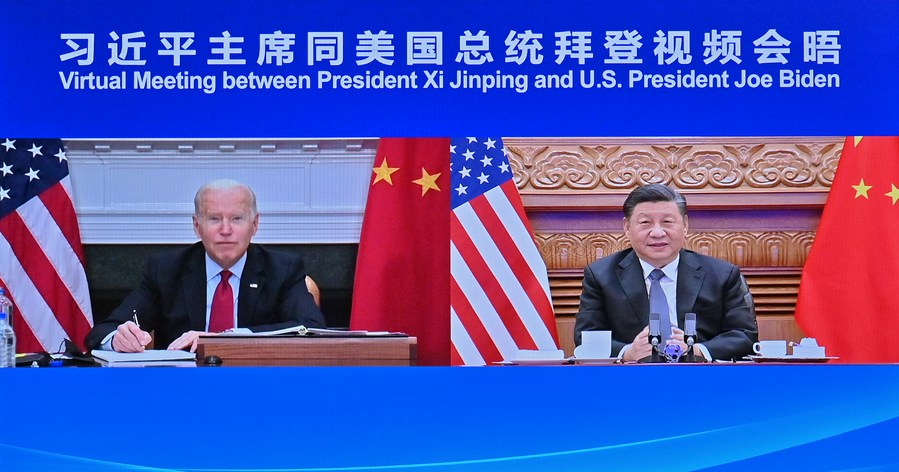

In his virtual meeting with U.S. President Joe Biden on November 16, President Xi Jinping, from the perspective of a community with a shared future for humanity, pointed out that China and the United States need to increase their communication and cooperation, tend to their domestic affairs and, at the same time, shoulder their share of international responsibilities, as well as work together to advance the noble cause of world peace and development. Xi also expressed his readiness to work with President Biden to build consensus and take active steps toward moving China-U.S. relations in a positive direction as doing so will advance the interests of both populations and meet the expectations of the international community.

This is the third significant interaction between the two heads of state since Biden took office in January. The meeting is expected to bring some positive results, but as to what extent it will help ease current tensions between the two countries, one can only wait and see. The root causes of the tense bilateral relationship are on the part of the U.S., and the U.S. is unlikely to give up its policy of containing China just because of a couple of meetings held between the two countries’ top leaders.

The containment strategy

Both President Xi and President Biden expressed their will to improve current China-U.S. relations during their meeting. Biden, too, expressed his willingness to get the bilateral relationship back on track.

China-U.S. relations have seen some positive changes as of late. The latter once again began to allow fully vaccinated foreigners to enter its borders in early November, including Chinese travelers. The two countries also released the China-U.S. Joint Glasgow Declaration on Enhancing Climate Action in the 2020s on November 10, further strengthening their cooperation in response to climate change.

However, tangible improvements in China-U.S. relations have yet to come. Increased tariffs on Chinese goods, a legacy from the Donald Trump administration, remain. The U.S. is still busy cracking down on Chinese companies. Chinese students keep being harassed and interrogated by the U.S. customs officers when going through entry procedures at U.S. airports. Economic, trade and people-to-people exchanges between both nations have not yet gotten back to normal, contradicting Biden’s words.

The Biden administration defines the China-U.S. relationship as a “competitive” one, essentially a continuation of the Trump administration’s China policy. The U.S. strategic intention to keep China in check is embedded in its clampdowns on China in all aspects of politics, military, science and technology, as well as its policy towards Taiwan, Hong Kong and Xinjiang, its politically motivated attempt to trace the origins of the novel coronavirus and an unrelenting punch to Chinese tech companies.

The new defense and security pact forged among the UK, the U.S. and Australia, meant to strengthen nuclear submarine cooperation, could be taken as a new act executed by the Biden administration to curb China. This alliance, a product of Cold War mentality, is not only a violation of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, amplifying the risk of nuclear propagation, but is also damaging stability and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region, which was hard-won thanks to decades of arduous efforts courtesy of China and other countries in the region.

In this sense, the meeting between the two leaders, rationally speaking, is more a gesture of mutual good will to improve their relations rather than anything concrete.

The U.S. hostility

On one hand, the U.S. side has made it clear they want to get China-U.S. relations back in shape, actively engaging in talks with China’s leadership; on the other hand, the U.S. still holds a hostile alertness towards China. The Biden administration’s China policy implies their bewilderment on this issue. China’s rapid rise has caught the U.S. on the wrong foot, so when feeling it hard to adapt to this new reality, the U.S. has not been able to develop a proper way to team up with China just yet.

Western scholars tend to define the current conflicts between both countries as the confrontation between civilizations, between socialist and capitalist systems, or between the concept of a community with a shared future for humanity and that of “America First.” As a matter of fact, these theories are nothing but an excuse to paper over the essence of present-day China-U.S. tensions, which are growing on the hotbed of Washington’s imagined “threat” and “insecurity.”

The U.S. has a pattern to follow when facing emerging “competitors.” The EU and the U.S. are all in the Western civilization camp, but whenever the EU’s development starts eating into U.S. interests, the American Government never hesitates to wield its baton of sanctions. Just like it does in its hostility towards China, in turn rendering the civilization conflict theory unbelievable. Japan also pursues the capitalist system, but when its takeoff overshadowed the American “comfort zone,” it only took agreements in the 1980s to send the Japanese economy into recession, which still seems tepid even to this day. Russia, too, practices a capitalist system, but the crackdown on the country courtesy of the U.S. is even tougher than the one on China. The social system argument subsequently doesn’t hold up. Although the conflicts between development concepts seem plausible, the concept of a community with a shared future for humanity means to realize common prosperity for the whole world, which can only benefit the U.S.

An analysis of the history of China-U.S. interaction, combined with American officials’ rhetoric regarding China on various occasions and its general attitude towards China thus far, reveals that the theory of conflicting interests is the more persuasive one. The downward spiral of the China-U.S. relationship can be traced back to 2010, a year of symbolic significance in the two countries’ exchanges, when China’s GDP surpassed that of Japan and it elevated itself to the second largest economy in the world. Also, with its manufacturing production overtaking that of the U.S., China became the world’s largest manufacturing powerhouse that same year.

China’s rapid development has delivered a blow to the U.S. hegemony. Sniffing China’s threat on its global interests, then U.S. President Barack Obama proposed a U.S. pivot to the Asia-Pacific region, followed by the Trump administration’s “America First” policy and a trade war waged on China. The Biden administration is merely a continuation of its predecessor’s China policy.

Win-win on the table

China-U.S. relations have now come to a crossroads. Decoupling and confrontations are in the interest of neither party. The most striking outcome of the virtual meeting is probably the display of good will on both sides. President Xi proposed during the meeting that China and the U.S. should respect one another, coexist in peace and pursue win-win cooperation. President Biden agreed that the two countries should make the relationship work and not mess it up.

Win-win cooperation between both nations remains a viable option. The U.S. is encountering difficulties in its development. These difficulties do not hail from external forces, but stem from its own stagnated process of moving forward. The best way out is to turn to international cooperation and multilateralism. China’s development is driven by its endogenous dynamic and the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation manifests as an irreversible trend.

Both countries are now at a critical stage of development. As the world’s two largest economies and permanent members of the UN Security Council, China and the U.S. need to take on the responsibility that comes with being a major global power, and their cooperation not only benefits themselves, but also bodes well for peace and stability worldwide.

Currently, the biggest stumbling block in the relationship is the American outlook on China’s rapid growth, an important question facing many other countries.

A rational, just and objective attitude towards China’s development and the ability to extract opportunities from it are important for the mutual benefit and common development of both countries. Inadaptability to China’s rise or speculation on and even miscalculation of the current situation would be detrimental to bilateral cooperation, yet the U.S. seems somewhat stuck in its outdated mindset. It’s high time for America to make a change.To treat China as a partner will do the U.S. and its people much more good than to look at China as a competitor.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +