International Networks Can Bring Benefits and Collaboration to the Coronavirus-Torn World

Dismantling global value chains under the myopic guise of punishment, fear of vulnerability, or nationalism would not only be a rejection of the positive benefits of globalization but it would deny a coronavirus-torn world both the spirit and collaborative opportunities that are so desperately needed today.

Global supply chains–technically dubbed global value chains (GVCs)–have become weaponized in the economic battles of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. The target: China, the West’s favorite scapegoat in a self-serving blame game. Japan has set aside some 243 billion yen ($2.2 billion) of its record 108-trillion-yen ($1-trillion) rescue package to assist companies in pulling operations out of China. Larry Kudlow, top economic adviser to U.S. President Donald Trump, has hinted at providing similar relocation support for U.S. companies.

The goal is three-fold: Punish China for “causing” the coronavirus, eliminate a source of vulnerability in production lines of critical equipment, and bring back home (reshore) offshore platforms that have undermined and hollowed out domestic operations. While each goal has elicited support in some quarters, there are important counter-arguments that draw many of these concerns into serious question.

Counter points

First, punishment is in the eyes of the beholder. While the first COVID-19 cases were, indeed, reported in Hubei Province, central China, the virus traveled across borders with lightning speed in a tightly connected globalized world. No major country–from China and Japan to Italy or the U.S.–handled its initial outbreak with a deft display of aggressive and enlightened public health policy. Punishment resonates with those politicians seeking to deflect responsibility away from their own shortcomings in responding to this disease. History provides painful examples of how that can backfire. Look no further than the steep reparations imposed on Germany after the end of World War I.

Second, supply-chain vulnerability is indeed an undeniable risk of globalization. It didn’t start out that way. Back in the 1980s, inefficient Western economies became heavily enamored of Japan’s “just-in-time’ inventory management and production system (kanban). In response, costly stockpiles of parts and finished goods were all but eliminated and a physically proximate network of suppliers produced for demand, not for supply. Over the years that followed, breakthroughs in technologies, cheaper transportation networks and improved logistics broadened the proximity of supply chains to global networks. And GVCs were born, complete with built-in vulnerabilities to global suppliers.

Third, in times of stress, the weak link in a supply chain can unmask the tradeoff between efficiency and the potential for bottlenecks. Henry Farrell, a professor of political science and international affairs at the Elliott School at The George Washington University, and Abraham Newman, a professor and director of the Mortara Center for International Studies at Georgetown University, have developed a network-based theory of globalization–stressing the critical role of supply chains both in eliminating slack but also in serving as instruments of weaponized pressure. Elimination of slack fits the efficiency imperatives of the early kanban objectives while weaponization is reflected by the U.S. so-called entity list (i.e., the blacklisting of China’s Huawei). The problem is that the weak link could also turn into a serious bottleneck–implying that too much slack, or redundancy, has been taken out of the system. That point has become glaringly evident in the form of life-threatening shortfalls in foreign-made medical equipment and pharmaceuticals in the current pandemic.

Related to this point is the presumption that GVCs are easily malleable–that sourcing can quickly be redirected from one supplier to alternatives in foreign or home markets. That reasoning is implicit in the coronavirus-related relocation proposals of Japan and hints of the same in the U.S. Yet that belies the complexity of these networks and the considerable amount of time and effort it has taken to construct them. Before he became CEO of Apple, Tim Cook was the company’s chief operations officer, charged with supply chain management. In that capacity, it took him years to reengineer the iPhone supply chain. That can’t change overnight. Indeed, contrary to today’s accepted political wisdom clamoring for instant supply-chain liberation, recent research underscores the “stickiness” of GVCs.

Far more benefits

The very name, supply chain, biases this debate. There is far more to GVCs than the supply side of the economic equation. Equally, if not more important, are the efficiency dividends that accrue to consumers, the job-creating and poverty-reduction benefits that go to relatively poor nations, and the collaborate spirit that a coronavirus-torn world so desperately needs.

First, consumers are the ultimate beneficiaries of free trade, international specialization, and GVC-enabled cross-border connectivity. David Ricardo, a British economist, made the first two points over 200 years ago, and GVCs are, in essence, modern-day catalysts of basic Ricardian forces–providing expeditious delivery of an ever-expanding offering of high-quality, low-cost goods (and services) to global consumers. For consumers whose real incomes have been under chronic pressure, like those in the U.S. where median real wages have stagnated for some 30 years, the GVC-enabled boost to purchasing power has been especially important.

The reversal of that trend would have dire consequences. Take away the supply chain centered on a low-cost producer such as China, which has played a key role in holding inflation down and expanding household purchasing power in the U.S., and this story gets turned inside out. At a minimum, trade will get diverted to higher-cost foreign producers. Over time, the “ultimate fix” of reshoring would bring output back home to even higher-cost domestic production platforms. In both cases, U.S. consumers will be on the short end of the stick.

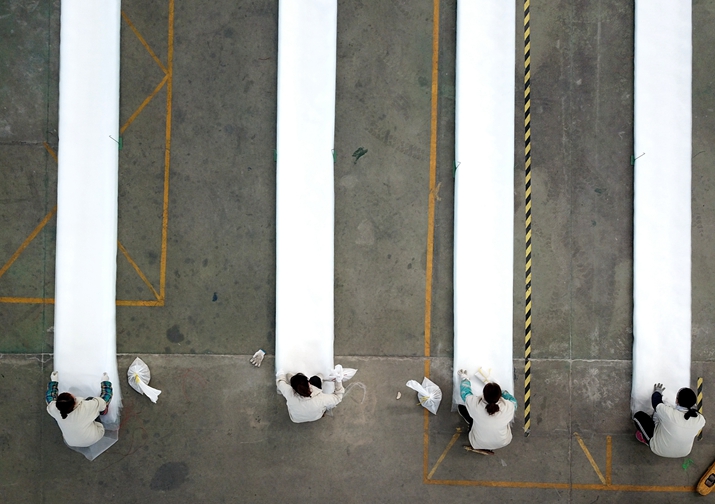

Second, GVCs have also provided an important spark to global development–boosting job creation and spurring poverty reduction in countless lower-income economies. Nowhere has this been more evident than in the case of China. Following its accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in late 2001, Chinese GDP growth averaged 9 percent for 18 years, while urban employment expanded by 200 million and poverty was reduced by over 500 million. By no coincidence, China’s economic growth in the aftermath of WTO accession was largely export-led, with GVCs playing an important role in driving that impetus. This trade- and GVC-led surge in economic development has been key in supporting China’s important role as an engine of global growth; from 2008 to 2018, China accounted for 37 percent of the cumulative increase in world output. Taking that away by GVC weaponization could pose significant risks to a post-pandemic global recovery.

Finally, the supply chain is a magnet for global cooperation and collaboration. It enables multinational corporations, governments, and multilateral institutions and regulators to come together under the broad umbrella of globalization. That, in turn, not only requires increased cross-border flows of trade, financial capital and information but it also leads to increased flows of talent and the related internationalization of global cities from New York and Hong Kong to London and Sydney.

Against risks

Globalization is under attack in many quarters today. Increased trade protectionism, mounting inequality, environmental degradation and now a raging pandemic have led many to question the wisdom, to say nothing of the practicality, of attempting to bring the world together. The supply chain, and the modern global production platform that it knits together, is an important part of the fabric of a modern global economy. It represents the latest advances in technology, production and assembly techniques, and near instantaneous delivery of both goods and services. Dismantling GVCs puts all that at risk.

The clamor for reshoring adds political miscalculation to economic risks. Shifting production from low-cost offshore platforms back to higher-cost alternatives would be the functional equivalent of a cruel tax on already wounded consumers. But dismantling GVCs under the myopic guise of punishment, fear of vulnerability, or nationalism would not only be a rejection of the positive benefits of globalization but it would deny a coronavirus-torn world both the spirit and collaborative opportunities that are so desperately needed today.

The author is a faculty member at Yale University and former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +