Is the U.S. Trying to Start a Currency War?

There is no doubt labeling China a currency manipulator has signaled a new phase in the Sino-U.S. trade dispute, one which China is more than equipped to fight.

When Donald Trump tweeted in 2011 to ask “when will the U.S. government finally classify China as a currency manipulator?”, not even the most audacious gambler would have bet that the brash, loud-mouthed TV host and property tycoon who’d sent it, would ever have been involved in instigating it.

And yet, such is the current unpredictability of international politics and the speed in which decisions are made, President Trump has done just that.

Just eight days ago both sides were engaging in talks, signifying a return to the sensible discussion and mutual respect agreed by President Xi Jinping and Trump in Osaka. The visit of Mnuchin and U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer to Shanghai, the city that witnessed the thawing of relations between the two countries forty-seven years ago, was supposed to act as a catalyst for subduing the current tensions.

Initial results seemed positive, with both sides happy at the “constructive” talks. China offered an olive branch in agreeing to buy more agricultural products from the U.S., fulfilling a key concern of the American team and both sides left reportedly satisfied and eager for further discussions in September.

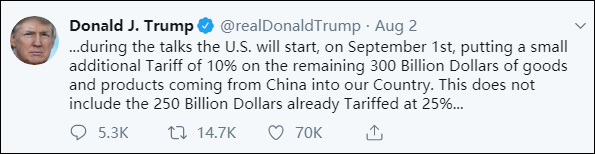

But no sooner had Mnuchin and Lighthizer touched down in America, the good-will generated from their discussions was eroded. Trump announced abruptly an escalation in tariffs, putting an additional 10 percent on the remaining US$300 billion of Chinese goods, which triggered a significant downturn in the markets.

Reacting to its volatility, the renminbi opened stable but lower the following Monday, breaking the 7 to 1-dollar mark for the first time since the 2008 financial crisis. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) blamed “unilateralism and the protectionist measures”, the market’s demand-supply relationship, and the fluctuating international exchange rate market as to why the marks that set the renminbi’s rate had moved.

Despite stabilizing on Tuesday, the U.S. deemed the short-term fluctuation an attempt “to gain an unfair competitive advantage in international trade” and would, therefore, ask the International Monetary Fund to “eliminate the unfair competitive advantage created by China’s latest actions”.

What Has Been the Response?

The PBCO has fervently denied the U.S. Treasury’s accusation, calling the decision “arbitrary” and “damaging” to the global economy.

“The U.S. labelling is an arbitrary unilateral and protectionist practice, which seriously damages international rules and will significantly impact the global economy and financial markets,” the PBOC said in a statement, conveying deep regret over the US Treasury’s decision.

It has not been alone in its condemnation of Trump’s latest policy move, with former Treasury officials voicing concern over his and Mnuchin’s decision.

Former U.S. Treasury Secretary and Chief Economist of the World Bank Larry Summers thinks Mnuchin’s decision is “problematic” and unjustified because the country does not meet the U.S. Treasury’s own criteria for being a currency manipulator.

China isn’t running a substantial current account surplus, nor is it trying to weaken its currency by selling it, and it isn’t allowing the renminbi to nose dive, Summers said.

“So, when you’re propping up your currency and you’re not running a trade surplus, you’re not manipulating your currency on any definition that is understood and accepted in the financial community—that’s why this seems to be a problematic situation”, the former Secretary said to Bloomberg.

Sarah Bloom Raskin, the former U.S. Deputy Secretary of the Treasury, thinks the decision was made without thorough consideration, given the timing of the announcement goes against common protocol.

When asked on CNN if “care” was taken over the decision, Raskin responded that “It wasn’t done by scheduling…It is usually done in a scheduled way”. The U.S. Treasury is required to publish semi-annually a report that makes public its decisions regarding currency manipulators, Raskin said, and though the latest such report published on May 28 mentions China as a country to watch, the report made no mention of China as a currency manipulator.

Yu Yongding, a fellow at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, believes this aspect make’s Trump and Mnuchin’s actions look tactile, a way of exploiting a situation without justification in order to further escalate tensions between China and the United States.

“It’s ridiculous to label [China] a currency manipulator simply because of one small exchange rate change in one trading day,” he added. “The US is trying to start a currency war, and it has rushed to find an excuse [to do so].”

Are We Heading for a Currency War?

Any move to engage in a currency war has been strongly rebuked by the PBOC, with the central bank’s governor, Yi Gang, stating China would not pursue the competitive devaluation of the renminbi and that it will maintain the stability and continuity of foreign exchange markets.

China will be committed to the promises on exchange rates made at all G20 summits and abide by a market-determined exchange rate system, Yi said.

China has little to gain by devaluing its currency, according to Song Xiangyan, an analyst with the PBOC, as the yuan’s depreciation cannot necessarily lift exports. A large devaluation could lead to panic capital outflow and competitive currency devaluation of China’s trading partners, which would undermine the country’s financial stability and hurt imports, Song added.

Trump, however, has made no such promises. He has consistently called for the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates and devalue the dollar to boost imports.

He most recently said in July that currency intervention wasn’t off the table, telling reporters “I didn’t say I’m not going to do something”.

Any boost to exports, however, would be offset by the damage to imports into the U.S., making them more expensive, which could cause inflation and hurt spending, leading to a stunt in economic growth.

There are already fears that Trump’s latest tariffs will increase the prospect of the American economy entering a recession, with Summer accusing Trump of “playing with fire” as these chances become “much higher” than two months ago, he former Treasury Secretary said.

China Still Has Options

Though not wanting to engage in a currency war, unlike the U.S., the Chinese government still has options to further counter American tariffs.

China still has room to further restrict buying American imports, having recently told companies to stop purchasing U.S. agricultural products in response to Trump increased tariffs on August 1.

And it is also yet to fully weaponize its near-monopoly on rare earth minerals, of which it controls more than 90 percent. These minerals are essential for electronic devices, with U.S. companies dependent on China for this—80 percent of its entire rare earth minerals supply came from China between 2014 and 2017.

Whatever decisions both sides make in the coming days, weeks and months, there is no doubt labeling China a currency manipulator has signaled a new phase in the Sino-U.S. trade dispute, one which China is more than equipped to fight.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +