It’s Time to Chart a Right Course for UK-China Relations

The rapprochement in UK-China relations should be regarded as a welcome development in an increasingly tumultuous global environment.

For the past six years, UK and Chinese officials have kept each other at arm’s length. Since 2018, there has been just one meeting between their leaders, with former Prime Minister Theresa May’s discussions with President Xi Jinping marking the last vestiges of the so-called “Golden Era.” That period of warm relations veered sharply south during the turbulent premierships of Boris Johnson, Liz Truss, and Rishi Sunak.

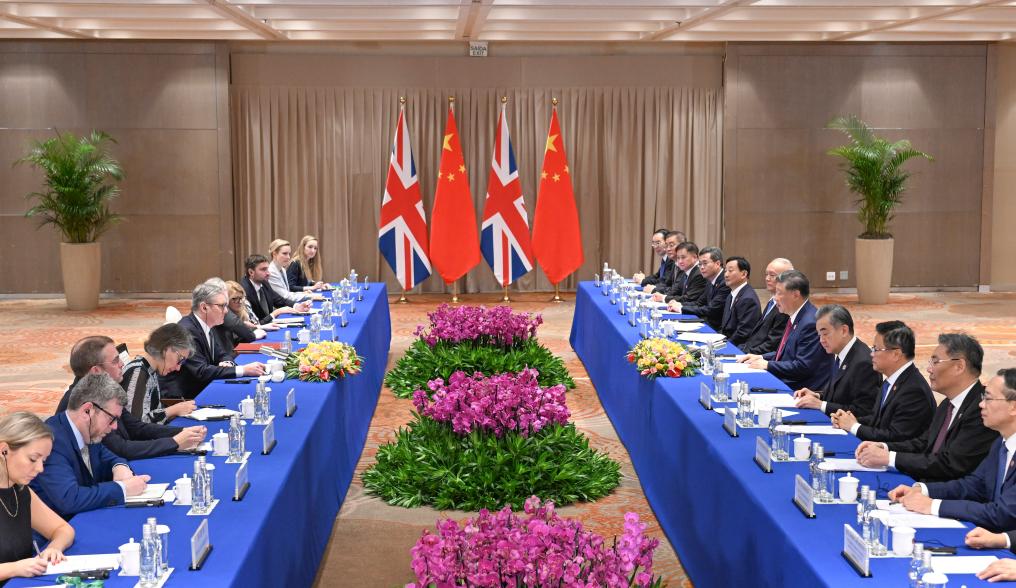

It is why the recent meeting between UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer and Chinese President Xi Jinping at the G20 Summit in Brazil was a historic moment, signalling a thaw in relations under the new UK administration.

Since Labour’s return to power in July, the government has prioritised a “serious, stable, and pragmatic re-engagement” with China. Foreign Secretary David Lammy has already met China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi twice—first in Laos during the ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in July and again last month during a two-day visit to Beijing and Shanghai. Chancellor Rachel Reeves has expressed eagerness to revive the UK-China Economic and Financial Dialogue, a key bilateral financial summit last held in 2019, and is expected to visit China in January 2025. Meanwhile, Trade Secretary Jonathan Reynolds has been vocal about the need for more engagement with China, calling the UK “an absolute outlier” compared to other G7 countries at the recent International Investment Summit.

Starmer has strong reasons to pursue a “pragmatic and serious relationship” with China. Sweeping to victory on the promise of delivering the highest sustained growth in the G7, he now faces the daunting task of delivering on that pledge. However, the realities of governance have already posed challenges. His first few months in office have been marked by internal upheaval, including the resignation of Chief of Staff Sue Gray, and a contentious Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting dominated by reparations for slavery—a topic the UK was unprepared to confront.

Economic challenges compound these issues. Recent GDP figures revealed just 0.1 percent growth in Q3 compared to 0.5 percent in Q2, a disappointing performance Starmer himself described as “not good enough.” The lukewarm reception to the government’s first budget and protests from farmers over new agricultural policies have added to the pressure.

To kickstart the economy, Starmer needs a win—and China offers an opportunity. With broader prospects in the Chinese market and growing disposable incomes, China represents a major destination for UK exports. The decline of Chinese direct investment in the UK over recent years has also cost towns and cities billions in infrastructure development. Furthermore, much of the technology vital to the UK’s green transition, such as solar panels, is produced in China, making improved relations essential for achieving climate goals.

China, too, has incentives to re-engage. Facing a challenging global trade environment, including steep tariffs on its goods from the EU, the U.S., and Canada, Beijing may view the UK as a valuable partner. The UK remains an outlier among G7 nations, refraining from imposing significant trade restrictions on China. Although the UK market is smaller than others, maintaining friendly relations with a stable European partner could serve China’s interests as it seeks reliable trade opportunities.

For China, the UK’s stability is also a draw. Next year’s elections in France and Germany could see far-right parties gain significant influence, injecting uncertainty into Europe’s political landscape. By contrast, the UK’s Labour government enjoys a strong parliamentary majority and has demonstrated its commitment to international law and responsible governance.

Closer UK-China relations would also provide a counterbalance to the potential upheaval posed by Donald Trump’s return to the White House. Having already nominated a number of China Hawks to his top team, Trump has also proposed 60 percent tariffs on Chinese goods as he aims to hit the Chinese economy hard. Reports suggest Trump could add 20 percent tariffs on other imports, which analysts have warned could potentially cost the UK economy up to £20 billion. In such a climate, the UK and China—both proponents of free trade—have an opportunity to collaborate and uphold these principles amid growing global protectionism.

Starmer and Xi’s meeting in Rio represents a chance to focus on areas of convergence and cooperation. The rapprochement in UK-China relations should be regarded as a welcome development in an increasingly tumultuous global environment.

The article reflects the author’s opinions, and not necessarily the views of China Focus.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +