Navigating Stormy Waters: What Can We Learn from Xi’s Davos Speech 2017?

2020 follows on from a year in which the world’s economy grew at its slowest pace since the global financial crisis, and the continued rise of protectionist policies and trade disputes.

Next week see’s the start of the World Economic Forum (WEF) Annual Meeting in the snow-topped ski resort of Davos. At the meeting world leaders, economists, business moguls and media leaders will flock to share their ideas and plans under the theme of “Stakeholders for a Cohesive and Sustainable World”, coming on the back of a tumultuous start to the new decade.

Although only three weeks old, this year has already seen its fair share of contention, with Australia currently burning to a cinder, the brink of war between Iran and America, and the start of another year of sluggish economic growth. 2020 follows on from a year in which the world’s economy grew at its slowest pace since the global financial crisis, and the continued rise of protectionist policies and trade disputes.

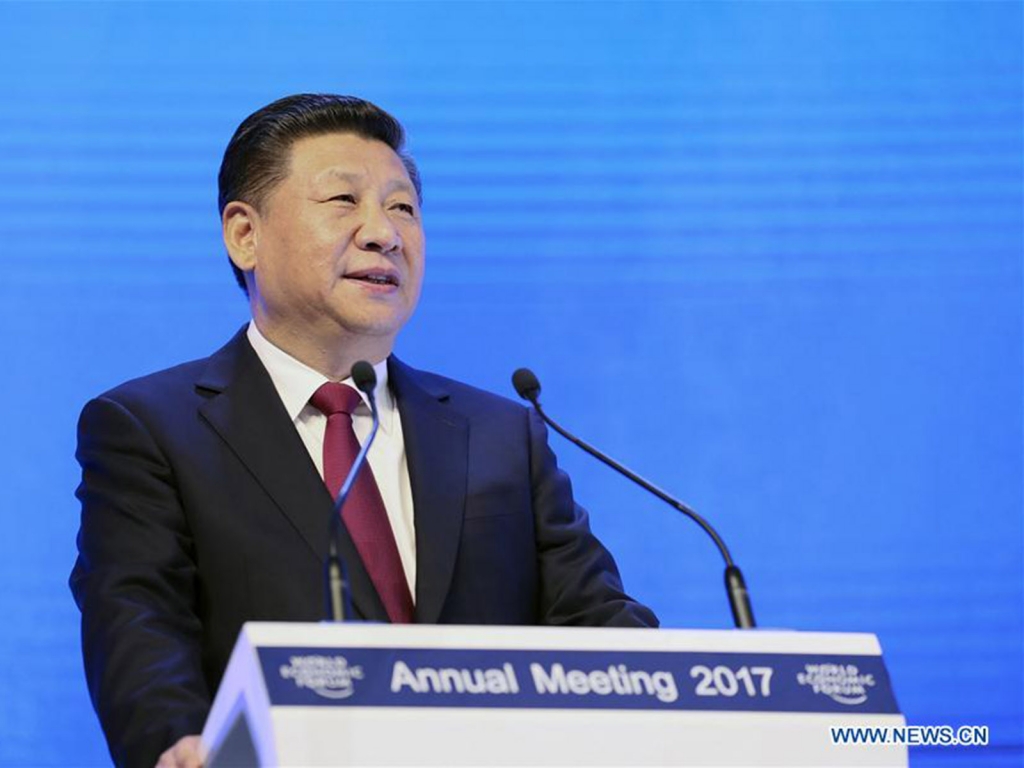

It is a situation not that unlike the one preceding Chinese President Xi Jinping’s keynote address at the WEF in 2017. That year saw Britain and America, two traditionally stalwart protectors of globalisation and multilateral trade, decide to go it alone, with their equally surprising decisions to leave the world’s largest single market and choice of a “protectionist” president respectively.

Rather than falling to the same damaging rhetoric and putting a further nail in the coffin of globalisation, President Xi instead gave a robust defence of globalised world governance and reaffirmed China’s commitment to upholding these ideals and its pursuit of greater opening up.

Between eloquent quotes by Dickens and Confucius, there were calls for multilateral approaches in solving world problems, the necessity of greater reforms to international institutions and the importance of new growth drivers to foster a dynamic, open world economy. There were cries for countries to resist the dark, lonely rooms of protectionism, and demands for the international community to seek actions that benefit the many and not only the few. By the end of his speech, there was a significant change in perception of China and President Xi himself, one that now saw him as a leading defender of globalization and the benefits it brings.

And while some have continued to follow a different path, three years later, China is still championing those key virtues of multilateralism, free trade and globalisation, by enacting sweeping reforms to open its economy up further, and working with international partners to foster collective economic growth and security.

A more open economy

Inside the country, China has looked to improve its domestic market for foreign businesses and investors by bringing in new legislation such as the Foreign Investment Law. The new law, which came into effect on January 1st, 2020, has legally banned forced technology transfers and granted foreign-invested businesses the same favourable treatment that their domestic counterparts receive.

The new law coincides with the announcement that the rules governing foreign-invested banks will be relaxed, allowing them to underwrite bonds issued by local governments. 135 bonds worth more than US$58.08 billion (400 billion yuan) will be available for fully foreign-funded banks, Sino-foreign joint venture banks and foreign banks’ branches to trade to clients, including overseas investors.

These improvements come on the back of greater trade between China and the rest of the world, which rose by 3.4 percent in 2019 to RMB 31.54 trillion, while imports grew by 1.6 percent to RMB 14.31 trillion during the same period. The first-phase trade deal between China and the US was signed Wednesday, containing measures for increased purchases of American products and services by at least US$200 billion in the next two years, including US$32 billion in agricultural products.

These improvements come on the back of greater trade between China and the rest of the world, which rose by 3.4 percent in 2019 to RMB 31.54 trillion, while imports grew by 1.6 percent to RMB 14.31 trillion during the same period. The first-phase trade deal between China and the US was signed Wednesday, containing measures for increased purchases of American products and services by at least US$200 billion in the next two years, including US$32 billion in agricultural products.

China has upheld its commitment to seek greater free trade by signing a further 3 FTA’s since the President’s Davos speech, bringing China’s total to sixteen. While it is in the process of negating eight others, the China International Import Expo has offered a greater opportunity for foreign businesses to directly speak to their Chinese counterparts, and the most recent event saw trade deals worth US$71.13 billion made, up from the year before.

International relations boosted

On the international front, China has promoted the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as a new driver for facilitating global growth and provided much needed infrastructure investment for countries across Asia, Africa and Europe. 199 cooperation documents have been signed with various countries and organisations regarding the Initiative so far, and according to the World Bank, if fully implemented, it could see increases in trade ranging from 1.7 to 6.2 percent for the world, and rises in global real income by 0.7 to 2.9 percent. Trade between China and BRI countries has now become indispensably locked, with China becoming 15 member countries’ largest trading partners, and trade with BRI countries now accounts for 30 percent of China’s overall trade.

China has also been a key player in negotiations for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which if agreed this year as China hopes, would link 16 countries including 10 from South east Asia as well as Japan, South Korea, India, New Zealand, Australia and China, half the world’s population and 34 percent of its GDP, making it the largest free trade area in the world.

And the country has worked with the IMF, World Bank and United Nations in efforts to solve important world problems, including the environment and world peace. China provides more troops to UN peacekeeping missions than any other, and has consistently paid its yearly contribution to the institution punctually and in full. At the same time, it has looked to use international platforms such as the BRICS Summit, The Conference on Dialogue of Asian Civilizations and the Belt and Road Forums to highlight the need for reform to these international institutions so they can better represent the needs of the entire international community, rather than just a select few.

As Xi acknowledged in his speech three years ago, “the road of human civilization has never been a smooth one, and that mankind has made progress by surmounting difficulties”. This year’s summit finds itself at a crossroads just as it did in 2017 and although President Xi will not be there to offer his input—Chinese Vice Premier Han Zheng will attend instead—the ideas he put forward and the actions of his country since, will give inspiration to those attending that these difficulties can be overcome.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +