Pride and Passion

Enthusiasm for and dedication to space science have propelled Chinese scientists to new heights.

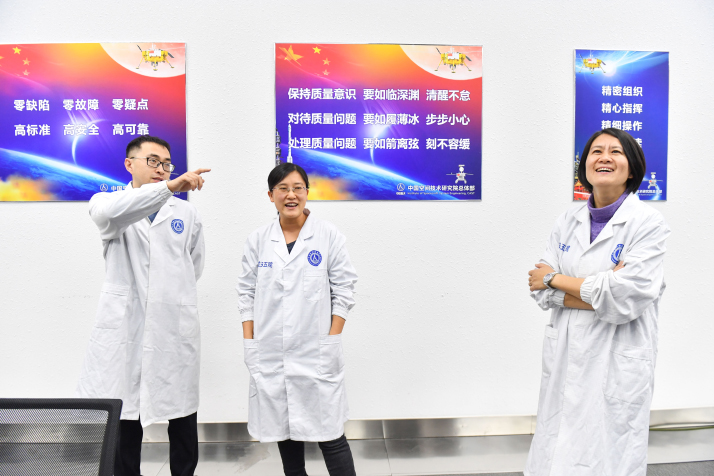

On aerospace engineer Wen Bo’s cellphone, there are four photos of herself in the same pose and against the same backdrop, but taken at four different junctures marking milestones in her career as well as China’s lunar probing program.

The first photo was taken in 2007, the year she started working at the China Academy of Space Technology (CAST) upon graduating from university and also the year China launched Chang’e-1, its first lunar probe. The second, third and fourth photos were taken right after the launches of the country’s second lunar probe in 2010, the third in 2013, and the most recent one in December 2018, respectively.

“More than 10 years have flown by in the blink of an eye,” she remarked while flipping through the photos taken in front of the gate of CAST.

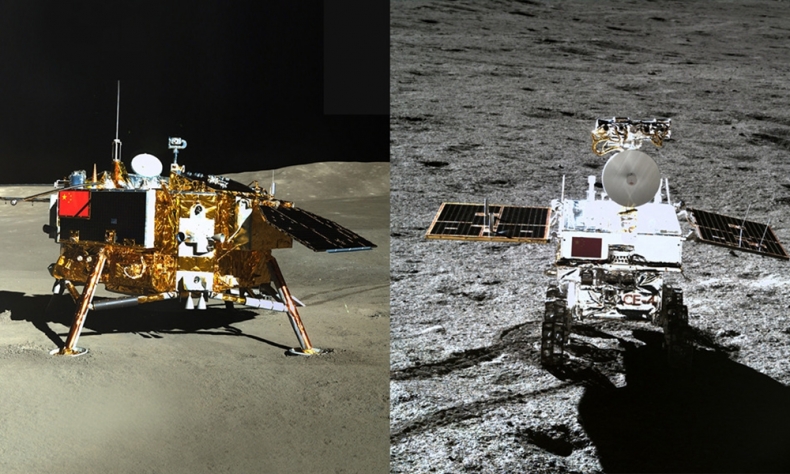

China’s fifth lunar probe, Chang’e-4 made the first ever soft-landing by a spacecraft on the far side of the Moon on January 3, and the China National Space Administration announced the lunar probe mission a success on January 11.

While watching the lander touch down on the Moon at the Beijing Aerospace Control Center, Zhang He, Executive Director of the Chang’e-4 probe project, could not hold back her tears.

Speaking about that emotional moment, Zhang told Beijing Review during an interview at her workplace on January 25, “I was very excited. For the past three to four years, the team has worked together diligently. The success was hard earned.”

Meeting challenges

“I am proud to have taken part in this mission,” Zhang said. “We have done things that have never been done, and have overcome many difficulties.”

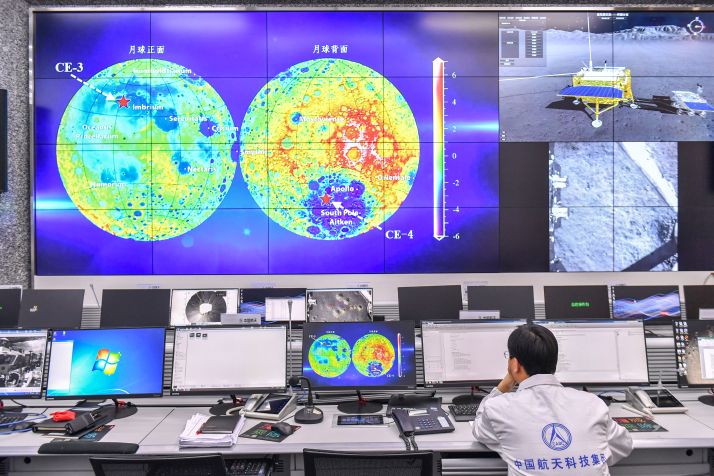

One of the main challenges in probing the far side of the Moon, she said, is the difficulty in telecommunications because it is not directly accessible to signals from Earth, so a communication satellite is necessary to relay signals.

Another challenge is the fact that the far side has been more frequently bombarded by shooting stars and meteorites, so the terrain is more rugged, which poses a high risk for landing, which could lead to the lander capsizing or crashing.

To overcome this difficulty, a relatively safe landing site was chosen. Zhang and other team members looked up many relevant reference materials, consulted a number of aerospace scientists and analyzed lunar soil and landscape characteristics to identify a site. Eventually, Li Fei, a key designer of the lander, picked a target landing site in the Von Karman crater which is relatively flat. Li, born in the 1980s, is nicknamed a “walking encyclopedia” for his broad-range of knowledge.

In addition, the lander was made smarter with artificial intelligence technology, Zhang said. Sensors measuring velocity and distance that can process 3D-images were installed on the lander so that it can analyze surface declivity, identify rocks and dodge obstacles. Zhang added that the technology is on the cutting edge internationally.

Since the Moon’s far side is also more pockmarked than the near side, the rover Yutu-2 faces bigger challenges than its predecessor Yutu which was sent to the Moon in 2013. Wen, a key designer of Yutu-2, said the rover was improved significantly to prevent mechanical failure.

After the rover reached the lunar surface, Wen is now responsible for controlling it remotely. She said that since the terrain is very complex, after every step, the rover must stop and photograph the surface and send data back to Earth via the relay satellite. Scientists on Earth then process the data and chart a route for it to follow. Wen said the rover’s antennas need to be adjusted to point toward the relay satellite so it can send signals, while the solar panels need to tilt toward the Sun to maximize power generation.

These challenges also promise many opportunities, Zhang said, adding that the far side is older than the near side, so studying its soil may shed more light on the origin and evolution of the Moon.

Moreover, the far side is an ideal place for low-frequency radio astronomical observations as the Moon blocks radio interference from Earth. Zhang explained that Earth has an ionosphere, which makes it difficult to receive low-frequency radio signals. Experiments need to be carried out in space to capture weak signals emitted from remote celestial bodies to study the origin and evolution of stars, galaxies and the universe. The experiments in near-Earth orbits are vulnerable to electromagnetic disturbance from Earth, but from the far side of the Moon, there is no interference from Earth.

Dedicated team

Usually, it takes three to four years to develop a lunar probe, which involves tens of thousands of people, Zhang said. For Chang’e-4, models were designed first and then parts developed, manufactured, assembled and tested. The lander consists of more than 200 devices and the rover of nearly 100, which were tested and revised over and over again.

Since the aerospace industry bears great significance to national development and to humanity as a whole, aerospace engineers are usually passionate about their work and totally devoted to it, she said.

“The most prominent feature of a spacecraft is that once launched, it is virtually irreparable, unlike a car that can be recalled if found to be defective or a plane that can be periodically maintained,” she explained. Any negligence can throw our years of hard work down the drain, thus aerospace engineers attach great importance to quality, she said, “We must identify all potential risks and try our best to control them.”

“The space industry is high-risk and needs long-term investment, so everyone is under a great deal of pressure,” Li said. On the wall of an aerospace control room, opposite to gigantic screens, there are several boards that read, “Zero defect, zero failure… high standards,” reminding the staff to be meticulous in their work.

In addition to being cautious and detail-oriented, Zhang’s colleagues often race against time to beat deadlines. The developers of Chang’e-4 lunar probe often worked overtime, and at different points, even moved into a hotel next door to the CAST to save commuting time.

Moreover, not all work is done in comfortable air-conditioned offices. Some tests are carried out in northeast China where winter is very cold and some in the northwest in desolate areas of the Gobi Desert. However, Zhang’s colleagues have no complaints about poor living environments.

Work-life balance

It has been more than two decades since Zhang started working at CAST after graduating from Beihang University, previously known as Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, the first institution of higher education in aeronautics and astronautics established after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. During this period she has grown from a new recruit analyzing dynamics to the executive director of the country’s second lunar-landing project.

She is also the mother of a teenage son. As a career mother, she does not think her professional and family roles are contradictory. “A working mother is a role model for her child,” she said, adding that her son also loves science.

Admittedly, some of Zhang’s colleagues have missed some important moments in their children’s life because of work assignments. When Cheng Ming, an aerospace engineer, went to the Xichang Satellite Launch Center to make last-minute preparations for the launch of Chang’e-4 in December last year, his son had an operation at the same time. Actually, five years ago, Cheng missed his son’s birth because he was busy preparing for the launch of Chang’e-3.

Nonetheless, Cheng’s sense of guilt was alleviated as he proudly explained to his son that his father helped send a probe to the Moon. Cheng said that this sense of pride is his motivation for pursuing a career in space science.

By Wang Hairong

Source: Beijing Review

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +