Remember the Past, Plan for the Future

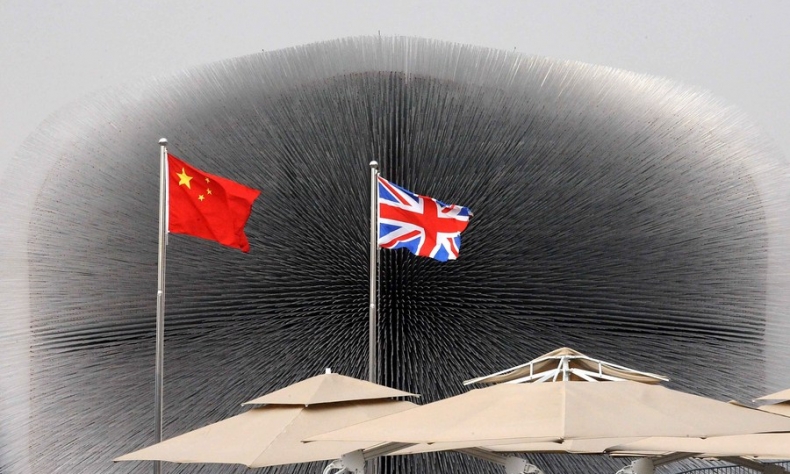

It is no longer the case that China is distant and remote. These days, it is a part of most people in education’s lived environment.

In 1816, Lord Amherst led the second significant embassy to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). One of its best accounts came from George Staunton, who had, as a young boy, taken part in the first, and better known, visit to China by George Macartney in 1793-94. Over the two decades that ensued, Staunton had learned to read and write Chinese to near-native proficiency. He had much to offer in terms of linguistic and practical advice.

Counting 72 members, the 1816 delegation could not be accused of being light on China expertise. Five of those taking part, including Staunton, possessed deep knowledge of the country they were visiting. One of them, Thomas Manning, was the first-recorded person from Britain to visit Tibet. Another had acquired formidable linguistic skills by working as a missionary in south China for many years. Despite this array of expertise, the delegation went down in history as a catastrophe. Lord Amherst failed in almost all the aims he had set out to achieve, not to mention his inability to meet the ruling emperor, Jiaqing.

Lessons from history

History tells us a cautionary tale. Knowing a lot about something is one thing; being able to use that knowledge well is completely different. Bear this in mind when looking at the recent report from the UK’s Higher Educational Policy Institute (HEPI), titled Understanding China: The Study of China and Mandarin (standard Chinese) in UK Schools and Universities.

This report, authored by Michael Natzler, HEPI’s Policy Officer, is the first addressing the issue of “capacity” to teach Chinese language skills in British schools for some decades. It comes on the back of the recognition that a deeper and more complex engagement with China is poised to become a fact of UK life, no matter people’s political opinions. This was recognized by the Integrated Review of British Foreign Policy undertaken in 2021, which paid particular attention to the rising importance of the People’s Republic.

In this context, the HEPI report presents some sobering statistics. Study of Mandarin at A Level (the exams taken around age 18 which are key for getting into university) has continued to fall over the last decade, because of the challenging nature of the paper. But there are broader issues. Language study generally in British schools has declined since being judged no longer a mandatory subject up to the age of 16. Complacency arising from the wide international usage of English is another part of the reason for this. Even so, the more important China becomes as an economy and geopolitical actor, the less British people seemingly want to seriously study it.

Part of the problem, not mentioned in the document, is the intimidating nature of the Chinese language and the simple cultural fact, for the UK at least, that as a more challenging subject, it relates only to the elite. Private schools, educating less than 10 percent of British school children, do devote more time and efforts than their state counterparts. That deepens the impression that somehow Chinese is the preserve of a specific privileged class. Such attitudes are reminiscent of Britain in its colonial peak a century and a half ago. They are utterly unfit for purpose today and belong to the realms of fantasy.

The HEPI report makes some practical and sensible suggestions. Chinese studies require more funding and better accessibility. More use needs to be made of one of the great, underutilized resources in the UK these days: the high number of students from China who, if they wished to do so, could serve as language partners—or even teachers.

It is no longer the case that China is distant and remote. These days, it is a part of most people in education’s lived environment. Relatively simple things like this can create a more flexible and attractive qualification in A Level Chinese language education. This is something that has been exhaustively discussed. It could be implemented fairly quickly after so much preparation. The only issue appears to be a government and administration in the UK distracted by many other issues which has never had the time to simply nod this proposal through.

Attitude vs analysis

But we still must remember the No.1 lesson from the Amherst 1816 embassy: Knowledge is one thing, but good deployment of it is something completely different. One of the great British issues is not so much one of knowledge itself, but more one of attitude. Sir Staunton’s experiences in the mid-19th century prove a case in point.

As historian Henrietta Harrison points out in an excellent new study, The Perils of Interpreting (Princeton University Press, 2022), Staunton’s experience following his election as member of parliament in 1818, after returning from his long-term China stint, is salutary. His knowledge of China was often a cause of suspicion, rather than an advert for his usefulness among his peers. He was regarded as being overly sympathetic toward China, his ideas compromised by his years spent in the country.

It’s easy to relate to Staunton’s plight today if you engage in public debate about China. While there are some world-class thinkers involved in issues relating to the country, their voices characterized by nuance, complexity and self-reflection, the media and political networks prefer stronger, more categorical fare.

It is easy to find people who have either limited, or in one or two cases no direct experience of China at all, who produce material brimming with conviction and certainty. To a certain extent, you could argue many of the latter do know more about China than most. Some of them in fact know a great deal. But the issue is the certainty with which they draw conclusions from the evidence they present and their commitment to an attitude toward China that puts politics before analysis and reflection.

It won’t be easy to change this because this will involve a cultural, more than an educational, transformation. It will involve a radical reappraisal of the global order prevailing since World War II, and of attitudes toward China—not just for decades, but for centuries—that have shifted from idealizing the place, to demonizing it—with no happy medium in between. Now, the latter seems to have more proponents.

My own personal attempt to try to contribute to bringing about change is to write a comprehensive history of Britain’s relations with China over the last half millennium. Huge numbers of separate studies of discrete areas of this history exist, but, as of yet, we have no accessible, general narrative. If that were to become available to the wider public, the British people might be able to better grasp the longstanding relationship between the two nations. If we want a better future, the best place to start will be the better understanding of our own past.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +