Space: Can China & US Boldly Go Where They’ve Never Gone Before?

Hawkish views within the Trump administration and the Wolf Amendment make any collaboration between China and the US in space difficult. But as both sides begin an unprecedented few years’ in space exploration and support for the amendment wanes, is now a chance for both countries to review cooperation among the stars?

China took another step towards a first manned space mission on May 5 with the inaugural flight of its Long March 5B carrier rocket.

Measuring eighteen-storeys-tall and weighing 849 tons, Long March 5B became the country’s most powerful rocket in terms of carrying capacity for low-Earth orbit and capped off a busy few weeks for the China National Space Administration (CNSA), having introduced the world to the name of its first planetary exploration mission to Mars—Tianwen—on April 24.

Meaning “Quest for Heavenly Truth”, the naming ceremony for the Mars mission put the CNSA on course to launch its first probe to the red planet in the next few months, with scientists predicting it could land on the Martian surface as early as July 2021. If successful, it would make China only the third country to land a spacecraft on the planet—after the United States and the former Soviet Union—a staggering achievement considering the country only launched its first rocket in 1970.

Zhang Kejian, head of the CNSA, reiterated at the ceremony that China is willing to work with the international community to make “new and greater contributions to exploring the mysteries of the universe”. Though cooperation has been at the heart of many of China’s ventures into space, including its latest two projects, both will once again see no formal collaboration between it and the world’s largest and most funded space agency: NASA.

Problem with the Wolf Amendment

Since Congress passed the Wolf Amendment in 2011 which barred the US from cooperating with China on space, both countries have had little to no communication regarding such matters. The amendment—named after Representative Frank Wolf (R-VA)—was passed as a way to “shut the door” on China and its space program as well as hinder the CNSA from working with other space agencies.

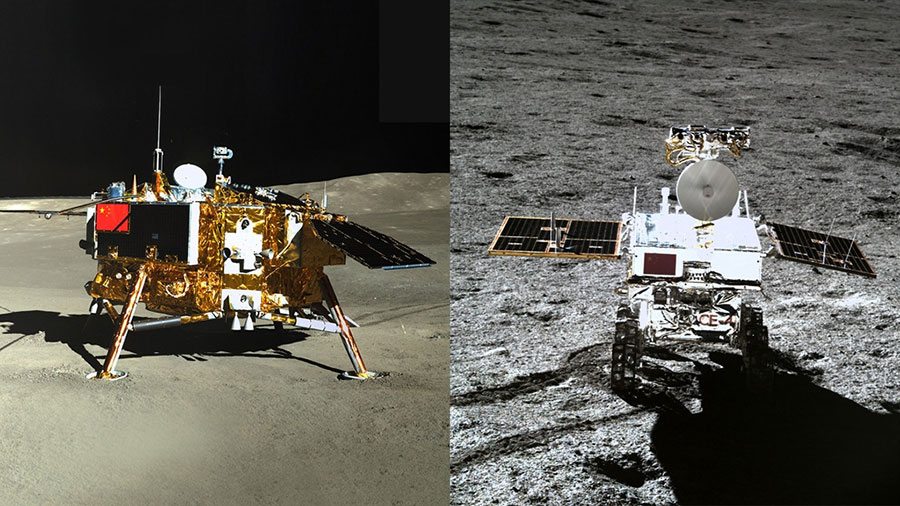

But in the nine years that have followed the amendment has struggled to fulfil its objectives. Rather than deterring innovation it has “pushed China to develop parallel capabilities” to NASA according to Makena Young, a research associate for the Aerospace Security Project at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). This has included the successful launch of its own Beidou Navigation Satellite System and the historic soft-landing of its Chang’e 4 lunar probe on the “dark-side” of the Moon last year.

The Wolf Amendment has also been unsuccessful in isolating the CNSA from the international space community, with the agency increasing its number of cooperation agreements with other countries and organizations to 121 in that time, as well as cooperating on manned space missions with Russia, Germany, France and the European Space Agency (ESA).

Todd Harrison, Director of the Aerospace Security Project and Defence Budget Analysis at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, believes the amendment has been a “complete failure” and as such requires the US to seek a different approach to their dealings with China in space.

“The Wolf Amendment, I believe, has largely proven ineffective in what it is trying to do. It’s not slowing China down,” Harrison said at a hearing conducted by the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission in April 2019. “I think that we ought to look at not only repealing that, but looking at areas where we can engage China in civil space missions.”

Aligning missions with common goals

Performing such a dramatic U-turn would be difficult but the current climate offers the greatest opportunity in years for this to happen. Right now, the world’s space agencies are experiencing a level of activity and investment unseen since the 1960s Space Race, with many of them overlapping and creating a superior opportunity for collaboration.

Specifically, both China and the US have shared objectives in exploring the Moon and conducting missions to Mars over the next few years. NASA is planning on sending its Perseverance Mars 2020 rover to the red planet around the same time as Tianwen 1 launches, as well as sending a manned crew to the Moon by 2024. The CNSA is also planning another series of trips the Moon starting with Chang’e 5’s voyage later this year to collect lunar samples, and a first Chinese manned-mission expected to the rock in the near future.

Jessica L. Martin, a Research Assistant at the Institute for China-America Studies (ICAS), believes this unprecedented synchronicity offers an opportunity for cooperation that would benefit both sides significantly.

“Both nations have tools and expertise to contribute which, if combined, could prove far more beneficial than any short-term gratification of space domination,” Martin says, pointing to the benefits of Chinese astronauts learning directly from their US counterparts on manned space missions, and US astronauts benefitting from using China’s unique Mars Base 1—a simulated research space-station in the Gobi Desert.

Cooperation is something both agencies have previously discussed, with some encouraging signs. NASA administrator James Bridenstine has previously said he was “hopeful” the two sides could share information that would be “mutually beneficial”, while at the 2018 International Astronautical Congress Zhang said he and Bridenstine held “very good discussion[s]” on bilateral cooperation.

Not unprecedented for competitors to work together

Some of those discussions have already brought tangible if tentative results, with China’s Chang’e 4 Moon landing witnessing significant cooperation between the CNSA and NASA for the first time since the Wolf Amendment was passed.

The CNSA was able to share the longitude, latitude and timing of the probe’s landing with NASA during the historic mission, while the American agency provided data from its observation of Chang’e 4’s landing and shared pictures from its satellites.

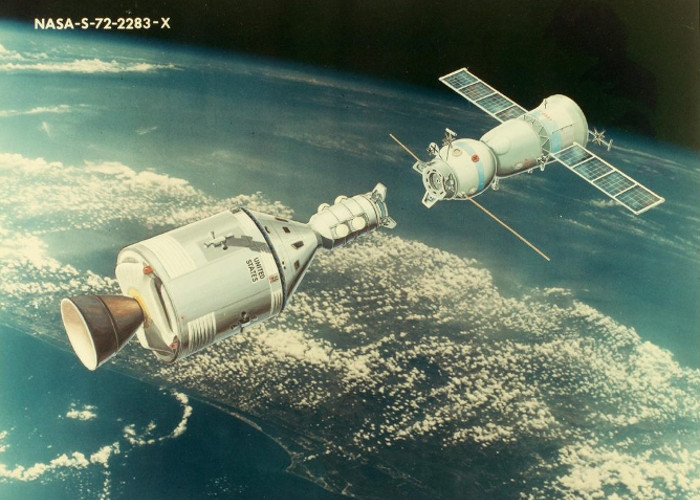

This type of collaboration is reminiscent of US-Soviet relations during the Cold War according to Harrison, and could well be a blueprint that China and the US follow over time.

“From the beginning of the space age, back in the 1960s, the United States and the Soviet Union started cooperating. One of the first things [the US] did was they started sharing technical data from satellites just to better understand what space environment they were starting to operate in”.

This included collaboration between US and Soviet teams on the Apollo-Soyuz test project in 1975, despite taking place at the height of the Cold War. Though relations remained thorny throughout the 1970s and 1980s, as well as most recently in 2014, space is one area where the US and Russia continue to enjoy a “steady” relationship. Harrison is “hopeful” that a similar approach can be adopted by Chinese and American leaders as they try to navigate through their many economic, political and military differences.

Trump administration makes collaboration difficult

Despite the opportune situation both the Chinese and American space agencies find themselves in politicians from both countries will ultimately determine to what extent further cooperation is conceivable.

The shift in narrative by the US from seeking scientific discovery in space towards gaining a military advantage over the past five-years has made opening lines of communication more difficult but also more important than ever. US President Donald Trump’s decision to create a US Space Command last year and the development of transportable space electronic warfare systems has created unease within the international community, and added with his administration’s hawkish attitude towards China, it makes collaboration a difficult prospect.

But the same could have been said of the US and Soviet Union during the height of the Cold War. Despite consistently coming to the verge of war they were able put tensions aside to work together in space successfully. The Wolf Amendment makes things just that little bit harder for China and the US but as support for the policy wanes, and both Chinese and American space agencies increase the ad-hoc cooperation they already experience, it is not farfetched to suggest that a more formal and expansive relationship between the two in space can develop in the near future.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +