Space: The Final Frontier in China-US Rivalry?

China’s space ambitions will continue to grow in cooperation with other nations, and therefore it is high-time cooperation rather than rivalry is brought into the China-US space relationship.

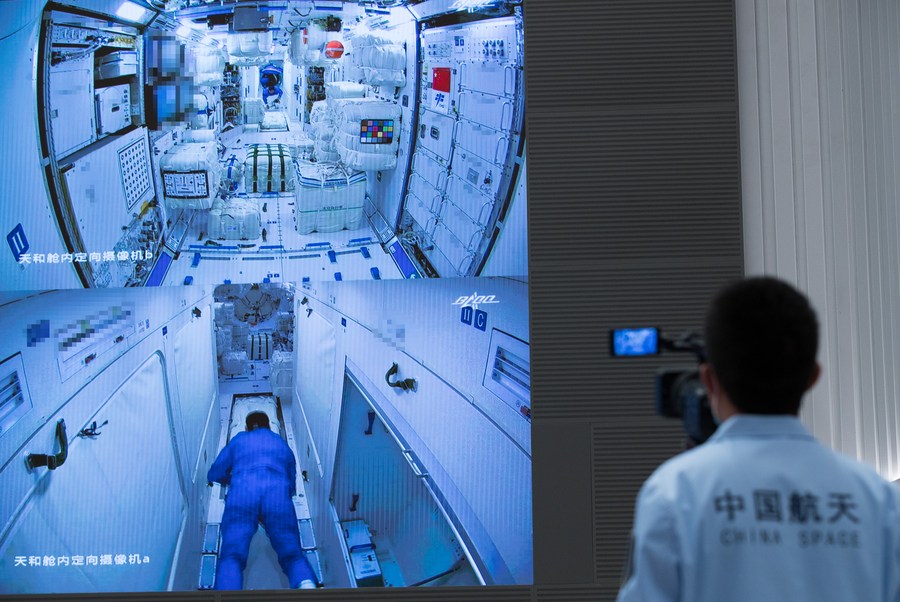

It has been nearly three weeks since three Chinese astronauts – known as taikonauts – blasted off to begin their three-month residency in Tianhe, a core module of the country’s brand-new space station.

In that time, interest has soared in their lives on board Tianhe. Vlogs recorded by the crew have kept hundreds of thousands of space fans entertained and informed, providing a never-before-seen insight into how the taikonauts eat, sleep and pass the time while thousands of miles away from home.

Most recently, fans have been absorbed by footage of two of the three taikonauts – Liu Boming and Tang Hongbo – performing the country’s first tandem spacewalk outside Tianhe, with a hashtag about the spacewalk garnering 200m views on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like platform, last Monday.

But just as excitement has grown in their latest mission at home, so too has speculation increased outside of the country, with officials – particularly in the United States – becoming increasingly concerned about the intentions and ambitions of China’s growing space program.

Space Race or Cooperate?

Such accusations have a habit of rearing their ugly head whenever China’s National Space Administration (CNSA) launches a new mission or program. Similar comments were made in relation to the agency’s mission to Mars earlier this year, as well as the successful landing of a probe on the “dark-side” of the moon in 2020. In fact, whenever China goes to space, you can be sure such commentary from the United States is bound to follow.

In Beijing, such charges are a source of frustration given how the country has looked to openly court cooperation with all countries in its space endeavours – from established spacefaring nations to developing countries looking to make their first waves in the atmosphere.

The new space station is a clear example of this. Already, Russian space agency Roscosmos’ has announced plans to send Russian astronauts to the new space station once it is complete, while China has extended an open invitation asking other countries to cooperate with it on the project.

While the station continues to be built, plans are also being made to construct an International Lunar Research Station based on the moon, which will be built in collaboration between the CNSA and Roscosmos. Similarly, officials at the CNSA have called out to international partners to cooperate on the station, and those from the European Space Agency (ESA), the CNES of France, as well as countries including Thailand, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have already expressed serious interest in cooperating.

The CNSA also currently has a number of German, French and Italian astronauts training at their bases in China in preparation of joint missions in the future – a further sign of closer cooperation.

Cooperation not universal

Cooperation is therefore a key characteristic of China’s past and future space projects, attracting like-minded nations who feel space exploration should be for the many and not the privileged few. But in Washington, China’s cooperative actions continue to be viewed as a smokescreen for its more sinister plans to dominate space.

That might be because China’s own brand of cooperation is on a collision course with the US’s own recent cooperation push. The Artemis Accords, described by NASA as a code of conduct for spacefaring nations, has been used by the US to attract space agencies as a way of endorsing its plans for the future of space exploration.

Over the past year, the agency has courted a number of the world’s most important space agencies, but as of yet, few have decided to sign. Roscosmos, the ESA and the CNES have so far been deterred from joining the initiative given the growing feeling that Artemis may not be as cooperative as first thought. All three agencies have had zero involvement in the drafting the accords, while signing up to these rules would exclude them from further cooperation with China on space exploration – something in the current climate they appear unwilling to renegade on.

Wolf Amendment splits space in two

That China continues to be treated as an outlier in space by the US is down to the work of the infamous Wolf Amendment. Passed by the US Senate in 2011, the amendment continues to obstruct any cooperation between China and the US on Space, including international projects like the International Space Station.

Though its introduction has, to some extent, forced China to develop its space capabilities both alone and in cooperation with other friendly space nations, this success has created two diverging space leaders – one lead by the US, and another by China. Marco Aliberti, a resident fellow at the European Space Policy Institute in Austria, has warned that this current space era, where there are “two contending – and potentially conflicting – pathways for future lunar exploration activities,” is a potentially dangerous phenomenon, and one that could lead to greater instability.

For those who lived through the Cold War, this kind of rhetoric sounds distinctly familiar. Daily news bulletins would often warn of the deadly “Space Race” between the US and the Soviet Union, one they warned could morph into a hot conflict at the press of a button. Though close, thankfully, no such conflict materialized. But looking back at that time, one can see a clear distinction between the American and Soviet’s space relationship compared to the US and the China’s right now: Cooperation.

Cooperation key

Even during the tensest moments between the two sides, and when cooperation on Earth looked a distant possibility, the US and the Soviets were able to look to the stars and find common ground.

The 1975 Apollo-Soyuz Test Project may have been the first joint mission between the US and the Soviets, but cooperation between the two started far earlier in 1962 – the same year as the Cuban Missile Crisis. Throughout the Cold War the US and the Soviets used space as an arena for cooperation, even during their most precarious times, helping rid insecurities and creating trust that eventually spilled over into other areas of their relationship.

The implications of the Wolf Amendment means that, at present, such an opportunity is unlikely to appear, and this in itself should be a cause of great concern. Because as relations on Earth deteriorate quicker, with red lines being crossed at a now daily occurrence, the areas for cooperation between China and the US are reseeding quickly. Space – bar climate change – is perhaps one of the few areas where China and the US should look to cooperate, if not just for themselves, but also for the wider benefits cooperation can bring to understanding our solar system.

To do that would require the Wolf Amendment to be thrown out, but before that can happen, their needs to be a significant change in how Washington views China’s actions in space. Suspicion can only ever breed more suspicion, and given China’s space ambitions are only going to grow – in cooperation with other nations – it is now more important than ever that cooperation is brought into the China-US space relationship.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +