Strategic Independence Is Key

Today, the world stands at a historic crossroads. Rather than being a satellite of the U.S., the ROK can play its role as an independent participant in international collaboration.

The presidential election in the Republic of Korea (ROK) has attracted much attention as its location and growing economic and military capacity make it a country of increasing strategic importance. Conservative Yoon Suk-yeol secured a victory on March 10 by pulling ahead of his liberal rival by only 0.7 percentage point. As the U.S. pushes forward its Indo-Pacific Strategy, the role the ROK chooses to play in it under the new administration will impact not only its own development but also the regional landscape.

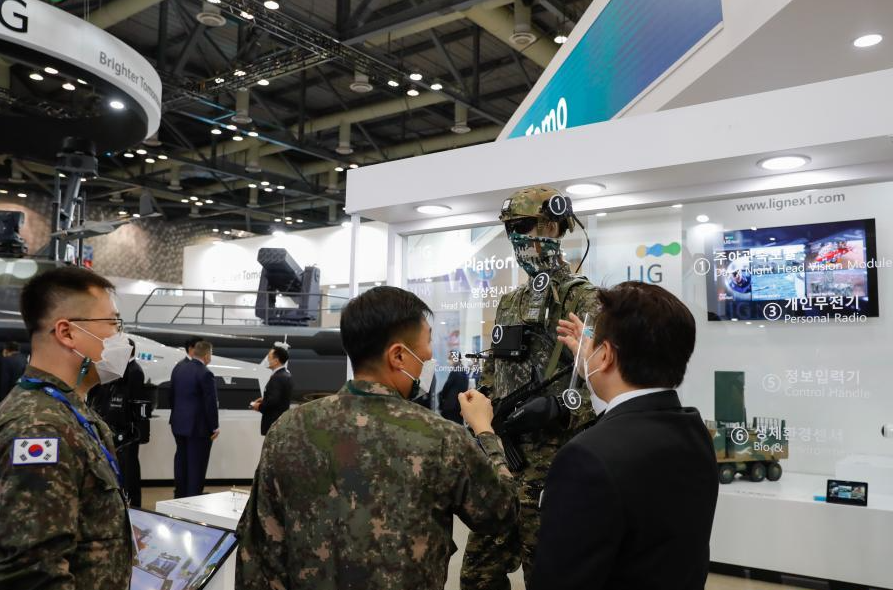

In August 2020, the ROK Ministry of National Defense released its Intermediate-Term National Defense Plan for fiscal years 2021-25. The $253-billion blueprint for defense spending over the coming five years includes satellite and missile defense programs purportedly aimed at deterring the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). Last September, when the DPRK test-fired two short-range ballistic missiles, the ROK quickly unveiled a series of missile technologies in response.

Some 10 years ago, the ROK military proposed a three-pronged defense system capable of preemptive strikes. During the election, Yoon further emphasized this military arrangement. However, this policy, designed to protect the ROK’s national security, instead has ended up leading to a security dilemma on the Korean Peninsula. Its increasingly strong military deterrence has intensified Pyongyang’s sense of insecurity, which could prompt the DPRK to strengthen its confrontational stance. In the end, a vicious spiral will emerge in which the stronger the ROK’s military power becomes, the more insecure it will feel.

The ROK has reason to develop its own military strength for self-defense. But there is a dangerous tendency of over-deterrence. Outside stakeholders such as the U.S. have always attempted to gain an edge by exploiting peninsula issues, and the deployment of Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) is an example. Under the guise of protecting the ROK from missile attacks from the DPRK, the U.S. intends to deploy THAAD in the ROK, with China being the presumed target.

Ties between China and the ROK hit a record low due to the launch of THAAD. To relieve China’s concerns, ROK President Moon Jae-in and his administration promised no additional THAAD deployments, no participation in the U.S.-led strategic missile defense system and no trilateral military alliance with the U.S. and Japan.

But during his election campaign, Yoon vowed to seek additional THAAD deployments. He even mentioned joining the anti-missile system led by the U.S. If Yoon puts his words into practice, this would not be deterrence against the DPRK, but a move to collaborate with the U.S. to contain China with disastrous consequences for the ROK’s ties with China. While Yoon’s statements have drawn widespread criticism, his future policy must be closely watched.

Meanwhile, the ROK endeavors to develop a blue-water navy, another move that could tip the balance. People with insights on the country have pointed out that a maritime force capable of operating globally is not necessary for the ROK’s self-defense. Seoul is advised not to move forward in this regard in a bid to serve U.S. interests, although its alliance with the U.S. has brought along opportunities for its development.

Today, the world stands at a historic crossroads. Rather than being a satellite of the U.S., the ROK can play its role as an independent participant in international collaboration.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +