The Arrest of Meng Wanzhou Has Nothing to Do with the Law

This seems to be a legal issue, but its solution has nothing to do with the law.

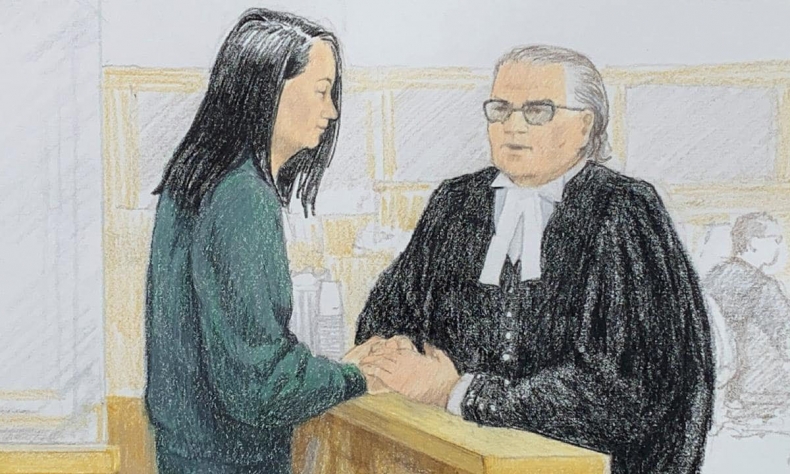

Canada’s legal system came under the spotlight in the beginning of this early December.

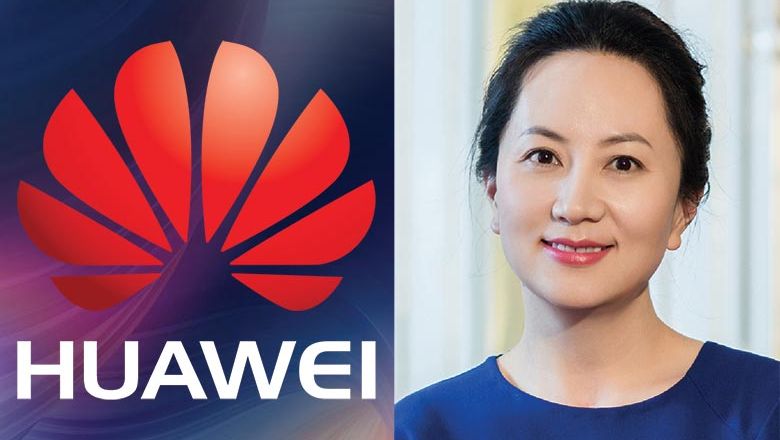

In the comments below a Reuters news report that Meng Wanzhou, Chief Financial Officer of China’s Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd., was arrested by Canadian authorities as she was changing planes in Vancouver, one netizen left his doubts about the legality of the process: So Canada has the right to arrest this woman because she works for a Chinese company and allegedly concealed business with Iran from banks in the United States?

This seems to be a legal issue, but its solution has nothing to do with the law.

According to the United States-Canada Extradition Treaty signed in 1999, the Canadian government is required to arrest accused individuals entering Canada in accordance with the requirements of the US authorities. This does not mean that the Canadian government doesn’t have its own consideration in this process: between 2008 and 2018, the Canadian government received a total of 1,210 extradition requests, but only 755 of the accused individuals were arrested. There is a theory that in order to discourage the extradition requirements of signatory member states, Canada generally does not arrest accused individuals in cases involving alleged crimes that are not criminal acts in Canada.

The accusations of Meng Wanzhou originated from HSBC. As a tainted witness, HSBC claimed that Huawei traded with Iran through a Hong Kong-based subsidiary, in violation of US economic sanctions imposed on Iran. The veracity of this accusation is now one of the focuses of the debate in court, but the only thing we know for certain is that this accusation does not constitute a crime in Canada – although Canada also follows in the footsteps of the United States and rein sanctions on Iran, only when a transaction with Iran occurs in Canada can it constitute a crime there.

Although the Canadian government has its own ideas on whether or not to make such arrests, 90% of individuals are extradited upon approval.

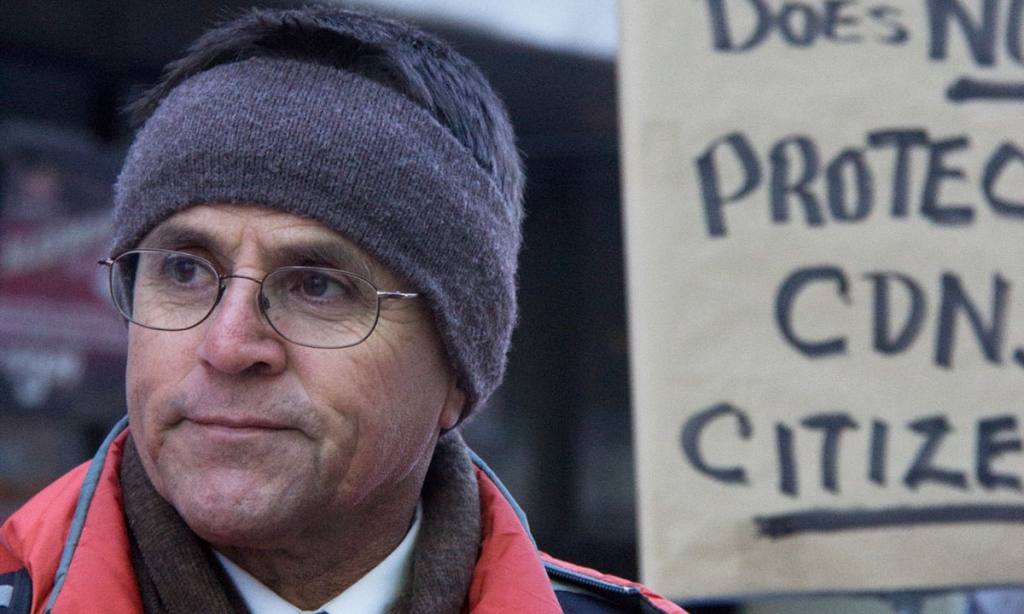

In 2014, Canadian professor Hassan Diab’s extradition caused uproar across Canadian society – Diab was an ordinary sociology professor, but after one lecture, a student approached and told Diab that he was the main suspect in the case of the bombings that struck Paris in 1980. Although no evidence linked Diab with this terrorist attack (in fact, Diab was taking exams in Lebanon at the time of the bombing), the professor was still extradited to France and held as a suspect in the case. The charges against him were not dropped until three years later for lack of evidence.

“We are constantly bending over backwards to accommodate whatever international request is made,” wrote British Columbia lawyer and author Garry Botting, one of Canada’s foremost authorities on extradition. “It’s not a question of ‘will we?’ but ‘how high would you like us to jump to accommodate you’.”

On December 10, reporters shouted questions at Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau as he descended the stairs, seemingly lost in thoughts, asking for his comments on the arrest.

“We are a country of the rule of law,” Trudeau said as he looked away from the cameras, adding a thoughtful reply: “We live up to our international obligations.”

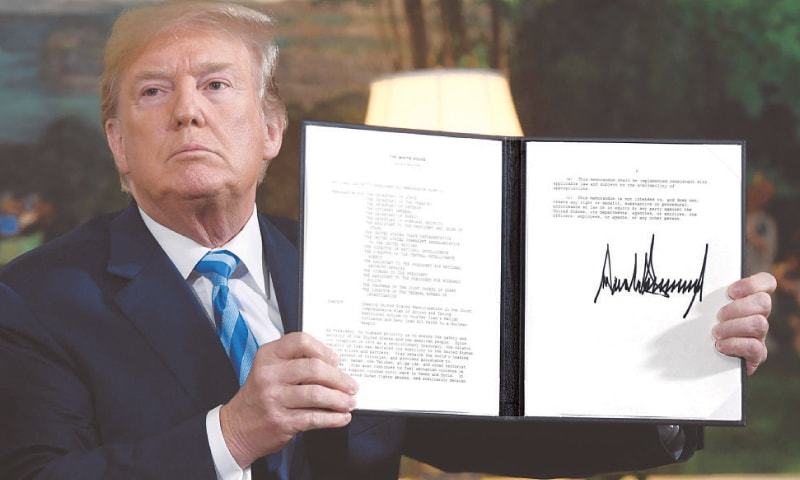

International obligation is certainly not a top priority for the President of United States, Donald Jr. Trump. Six months ago, he resolutely withdrew from the international law treaty reached by the five permanent members of the United Nations and the European Union with Iran – the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) on the Iranian nuclear issue. Trump persisted with his decision to withdrawal despite resistance from both home and abroad.

Three years ago, following 20 months of difficult negotiations, the five permanent members of the UN Security Council and the EU reached an agreement with Iran in Vienna, Austria. Iran agreed to strictly abide by the restrictions imposed on it by the nuclear agreement, and in return, the United States, the EU and the UN Security Council would lift long-standing sanctions on Iran. Then-US President Barack Obama confidently stated his successors in the White House “will be in a far stronger position” to restrain Iran afterwards.

However, only a little bit more than a year after he took office, Trump announced that the United States would withdraw from this hard-won peace treaty. In his 11 minute long speech, Trump ambiguously explained:, “Iranian promise was a lie because Israel published intelligence documents… conclusively showing the Iranian regime and its history of pursuing nuclear weapons”. Trump has not given any other reasons for the cancellation.

Among the other parties involved in the Iranian nuclear treaty, France and Britain have expressed regret over this move by the United States. China, Russia, the EU and Iran have indicated that they will continue to respect and maintain the treaty. Germany, Australia and Japan have also expressed that they did not agree with Trump’s decision.

Only the United States’ consistent Middle East allies Israel and Saudi Arabia are supportive of American withdrawal from the treaty. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called it “an historic move” from “courageous leadership”, and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman Al Saud expressed his full support for the decision of the US government at that time, he had not yet become mired in the controversy relating to the murder of a prominent Saudi journalist.

The way the executive power of the United States stands in parallel with its obligations under international law has always posed a theoretical dilemma. The US Constitution recognizes international law as one of the “supreme law of the land”, but does not explicitly state whether international law restricts the president or Congress. In recent years, the ideologies of the Republican and Democratic parties become more contrasting, the US stance on the issue of international law has become even more unpredictable.

This unpredictability, along with America’s unduly influence among its allies, makes international law a political tool for the Trump administration. Though Canada has stressed its judicial independence by all means – including posting, in English and Mandarin Chinese, a sign that reads in full capitalized letters: “INDEPENDENT JUSTICE PLEASE RESPECT” .

On December 11, shortly after Meng’s release on bail, Trump told the Reuters that he would intervene in the Justice Department’s case against a top executive at China’s Huawei Technologies if it would serve national security interests or help close a trade deal with China.

By Cao Yuan, Doctor of Harvard Law School

Editor: Yuan Yanan

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +