The Belt and Road Is Funding Global Infrastructure Investment. What About the Rest?

National Governments, especially from advanced economies, appear to have little appetite to fund their own infrastructure projects, let alone other countries.

In Mong Cai, Vietnam, crowds wait expectedly as bulging freight trucks carrying goods from Dongxing, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, in China, cross through customs.

The bustling northern city has become a thriving business hub, owing to its prime location across from Dongxing on the banks of the river Beilun and a new customs bridge linking the two, built through China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Completed in March this year, the 27.7-meter-wide Beilun II bridge has shortened waiting times for customs clearance and boosted border logistics, according to Huang Xiong, deputy director of Dongxing. Xiong expects the bridge to facilitate an increase in trade between Dongxing and Vietnam, which reached 24.45-billion-yuan last year, creating a brighter future for its local citizens.

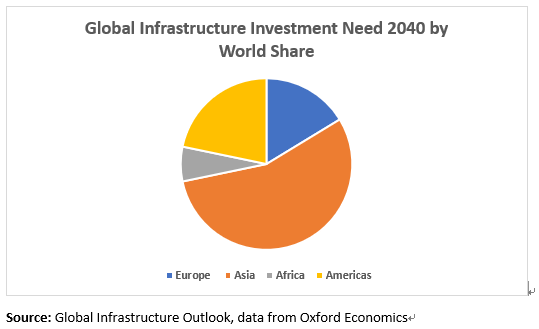

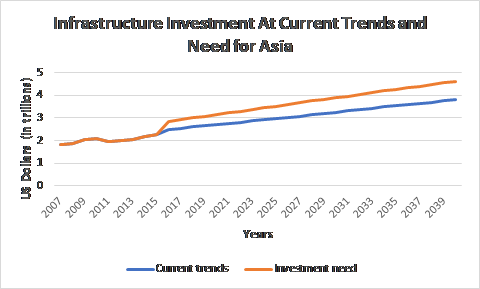

Belt and Road projects like the Beilun II bridge are essential for battling the huge infrastructure investment shortage currently engulfing Asia. According to a report by Global Infrastructure Outlook, a data hub affiliated with the G20, under current parameters it estimates fifty-nine percent of global infrastructure spending is needed in Asia, which will total $51 trillion by 2040.

Belt and Road’s Successful Six Years

Belt and Road’s Successful Six Years

China has over the last six years been committed to accelerating infrastructure connectivity in Asia and the rest of the world through its Belt and Road Initiative.

With 126 countries and 29 international organizations signing cooperation agreements with China, the BRI is working in partnership with host countries including Indonesia, Nigeria, Serbia, Lao, Russia, and Bolivia to reduce this shortage by constructing valuable infrastructure.

China has long championed the virtues of building infrastructure as a way of improving a country’s economic performance and living standards, has lifted 800 million people out of poverty and risen to the second largest economy in the world through this method.

Now, countries in the initiative are too reaping the benefits, with the BRI projects already creating 300,000 local jobs in the economic and trade cooperation zones built by Chinese enterprises abroad, and a goods trade volume of $6 trillion between China and participating countries over the past 5 years.

Comprehensive funding for the initiative has been provided by some of China’s most trusted institutions, with Zhang Qingsong, president of The Export-Import Bank of China (Eximbank) stating last week that it had provided more than a trillion yuan (US$149 billion) to over 1,800 projects since 2013, whilst the China Development Bank (CDB) had provided around $190 billion on more than 600 Belt and Road projects over the same period.

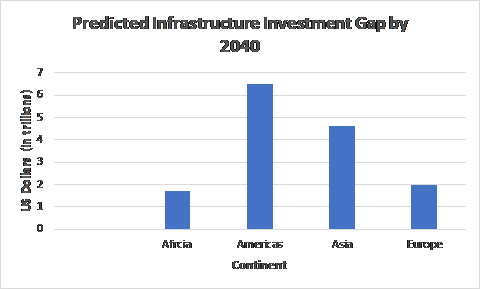

Despite this investment, current trends studied by Oxford Economics suggest the infrastructure investment gap for Asia will widen to $4.6 trillion by 2040 and global figures will total $15 trillion. Initiatives like the Belt and Road are needed now more than ever to bridge the gap and stop the ‘bottlenecking’ that insufficient infrastructure investment exerts on countries.

However, misconceptions, ill-informed-views, and lazy accusations are threatening to stunt the Belt and Road’s momentum.

This is an enormous miss-calculation on behalf of those countries and institutions, considering not only the current investment conditions but also the lack of serious alternatives offering anything as substantial and inclusive as the BRI.

The Alternatives Don’t Add Up

National Governments, especially from advanced economies, appear to have little appetite to fund their own infrastructure projects, let alone other countries. International Monetary Fund (IMF) Managing Director Christine Lagarde, speaking at the IMF’s Spring Meeting noted that current public investment on infrastructure was currently “on the short side” of what is expected.

“When you look at the numbers (advanced economies spending on infrastructure) we’re talking about an average of 1.7 percent of public investment which is twice as little as what it was in the 90s”, Lagarde said at the meeting.

Nor does the World Bank (WB) have the same enthusiasm for infrastructure projects as it did in the 1960s and 1970s, instead, pursuing safe projects that protect its “gold-standard environmental and social safeguards”. That may be acceptable for advanced economies but these standards make accessing funds for developing countries well out of reach.

David Dollar, who worked for over 20 years at the WB as a country director for China and Mongolia, believes it has forgone its position as a primary funder for infrastructure projects, with their current lending low on infrastructure investment.

“I would say that many developing countries have very serious infrastructure deficiencies. You can try to attract private investments, but they generally require a very high rate of return, so that’s expensive. Originally, the World Bank and other development banks were set up for this core function, but frankly, they’ve gotten out of the business. Only about 30 percent of World Bank lending is for infrastructure these days.”

Strategic cooperation agreements, regarded by others but not China as rivals to the Belt and Road Initiative, are also underwhelming in both their wording and funding.

The U.S. Better Utilisation of Investment Leading to Development (Build) Act was passed in October 2018 along with the newly created U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (“USDFC”) to distribute US$60 billion in loans and loan guarantees for U.S. businesses to invest in developing nations. That amount, however, is just a drop in the ocean when compared to the enormous US$1.3 trillion needed a year to fund infrastructure in Asia alone.

The EU-Asia Connectivity Strategy, released a few days before the BUILD Act passed, is even less detailed, with funding for its strategy still unspecified.

The European Commission’s report ‘Connecting Europe and Asia – Building blocks for an EU Strategy’ claims “the Commission does not aim at establishing an investment plan, although the EU’s existing and future financial instruments could offer some perspectives for supporting private investment in connectivity-related projects.”

The strategy is also light on detailing how the EU intends to construct connectivity with many East Asian countries, considering they have been left out of the report.

Thailand, Lao, Vietnam, and Burma are also missing, despite details on how the EU will connect with Australia and the U.S. China, as one of the largest funders of infrastructure in the area, also fails to be named in the report.

Belt and Road Cooperation Needed to Bridge Gap

“The broad support for the BRI shows aspiration from countries involved, developing countries in particular, for peace and development,” President Xi said at a symposium marking the fifth anniversary of the BRI in August last year.

“It does not differentiate countries by ideology nor play the zero-sum game. As long as countries are willing to join, they are welcome,” Xi said.

With the global infrastructure gap growing day-by-day, cooperating with an initiative that belongs to the world, that is open to all partners and upholds the principles of extensive consultation, joint contribution and shared beliefs would seem the logical proposal.

The UN, G20, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and other international and regional organizations all share this view, with the international bodies incorporating the BRI into their remits.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, a long-term supporter of the BRI, has encouraged member states to support it as a method for reaching the Sustainable Development Goals.

“(The Belt and Road is a) very important opportunity for enhancing the capacity to implement the Sustainable Development Goals and an important opportunity to launch green perspectives in the years to come,” Guterres told journalists on April 24.

Criticism for the sake of criticism helps no one, and certainly not those who are most in need of infrastructure investment. Ironically, much of the criticism has come from countries that already have the luxury of a sophisticated infrastructure network.

The second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation begin this week aiming to continue its work on peace and cooperation, openness and inclusiveness, mutual learning and mutual benefit, whilst also looking within itself to find improvements.

If more countries are “willing” to join the Belt and Road Initiative and cooperate on infrastructure projects like the Beilun II bridge, then the worlds ability to tackle the global infrastructure gap will improve dramatically.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +