The Great Sci-Tech Rivalry?

The current U.S. policy framework of scientific and technological competition with China violates both the principle of innovation and the law of the market.

In recent years, “China-U.S. sci-tech competition” has been a hot topic among U.S. politicians, academics, decision-makers and the general public. Competition between the two countries in science and technology has been taken by many as being a reality.

While Western narratives often focus on the negative aspects of the China-U.S. sci-tech relationship, those aspects are actually a tiny part of the big picture.

Cooperation over competition

Currently, hi-tech industries in China and the U.S. are at different development levels, which are far more cooperative than competitive.

On the one hand, the competitiveness of the U.S. hi-tech service industry is second to none. According to data released by U.S. National Science Board in 2022, the value-added output of knowledge and technology-intensive industries in the U.S. accounted for 37 percent of the world’s total, whereas that in China accounted for 11 percent.

On the other hand, in the current U.S.-led global value chain, some of China’s hi-tech manufacturing industries rely on importing advanced technologies from the U.S. and a few other industrialized countries to achieve their progress.

Since China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, its hi-tech manufacturing industries have grown remarkably through processing trade, a term that describes the process by which a domestic firm initially obtains raw materials or intermediate inputs from abroad and, after local processing, exports the value-added final goods.

At present, processing trade contributes nearly 60 percent of China’s hi-tech exports. However, large number of its parts and intermediate products are imported from Japan, the Republic of Korea and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) members, which are manufactured using technologies and upstream products from the U.S.

Additionally, research and development (R&D) investment by Chinese enterprises has seen rapid growth in recent years. In 2022, the number of Chinese enterprises entering the global top 2,500 in terms of R&D spending reached 762, second only to the U.S. But the reality remains, regardless of the differences in business areas between Chinese and American companies, even if the two sides invest the same amount in R&D, the output cannot be equivalent.

China is now regarded as a powerhouse with a fast-growing number of patent filings and scientific research output. According to a report released by the Institute of Scientific and Technical Information of China, from 2012 to 2022, highly cited Chinese papers listed on the Science Citation Index (SCI) increased by five times, reaching 63.5 percent of that of the U.S.

This strong growth is an indication of the increasingly close sci-tech cooperation between China and the U.S. as, in the past decade, 20 to 30 percent of highly cited Chinese papers have involved American partners.

At the same time, China still has a lot of room to commercialize its scientific and technological achievements. According to a survey by the China National Intellectual Property Administration, the industrialization rate of Chinese enterprises’ and universities’ invention patents was 48.1 percent and 16.9 percent, respectively, in 2022.

Moreover, China’s trade deficit in intellectual property rights in 2021 was $34.94 billion, while the U.S. had a surplus of $81.27 billion. Among all the royalties paid by China to other countries for the use of intellectual property that same year, 18.7 percent went to the U.S. In 2017, before Washington imposed tech export control measures on China, the proportion was 25.9 percent.

U.S. policies

In recent years, however, the U.S. has rearranged much of its policy framework on the idea of competing with China in sci-tech fields.

Its Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) and Science Act of 2022 and the Inflation Reduction Act, both being signed into law by President Joe Biden in August 2022, for example, restore strategic subsidies for science, technology and innovation in the name of “competing with China.”

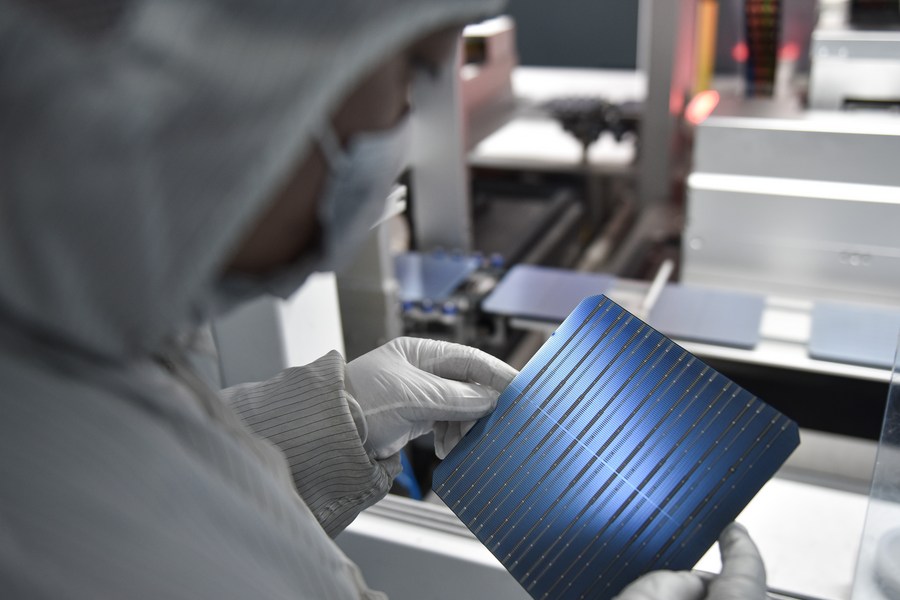

At the bilateral level, export controls and investment restrictions on China have been upgraded. As of June, the U.S. Department of Commerce has placed more than 600 Chinese enterprises on its export blacklist. These enterprises are mainly in 5G/6G, artificial intelligence (AI), quantum computing, photovoltaic fields. At the same time, the Biden administration is also pushing for establishing an outbound investment review mechanism which shall prohibit or restrict U.S. companies’ investment in the Chinese mainland in fields such as semiconductors and AI.

The U.S. is also fixated on assembling allies to contain China in science and technology. In June 2021, the U.S. and the EU established the Trade and Technology Council (TTC) to cooperate on investment reviews, export controls and AI technologies. The TTC is intended to serve as a vehicle to compete with China on emerging technology issues, according to U.S. political website The Hill.

These policies not only neglect the principles of openness and innovation, but also violate multilateral rules. In November 2022, Director General of the WTO Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala warned against the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act, arguing that a subsidy arms race could damage global trade at a moment when it’s needed to spur growth. “Let’s not make [a subsidy war] a reality, because of the cost to the global economy,” she said.

In December 2022, the leaders of nine EU countries, including France, Italy and Spain, met and concluded that the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act contains protectionist policies that would harm European industry and give U.S. companies an unfair competitive advantage.

In December 2022, China also filed a complaint against the U.S. chip export controls and other restrictive measures to the WTO.

China’s reaction

While the U.S. has become more aggressive in its sci-tech policies toward China, China is pursuing scientific and technological self-reliance and security. Its investment in science and technology has been increased and preparations have been made for a possible U.S.-forced tech decoupling.

As has been reiterated by the Chinese Government, China is committed to high-level opening up. It is ready to achieve common development with other countries by sharing opportunities. China, at the same time, will firmly defend its legitimate rights and interests. External containment and suppression cannot hold back China’s development. Instead, it will only strengthen China’s resolve to pursue self-reliance and technological innovation.

China remains focused on its own development. At the same time, it is open for cooperation. The Report to the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in October 2022, which outlines China’s policy priorities for the next five years and beyond, said the country “will expand science and technology exchange and cooperation with other countries,” and “cultivate an internationalized environment for research…” This shows that China has not been disturbed by the protectionist measures taken by the U.S. and is trying to create an open and innovative ecosystem.

Tensions between China and the U.S. seem to be easing as the two sides have resumed high-level contact recently. The U.S. has changed the wording of its policy toward China from “decoupling” to “de-risking.” But the two terms in essence are pretty much the same thing. The U.S., for example, continues to add more Chinese companies to its export blacklist and further expand the areas of restrictions.

In the long run, Washington’s expanding export controls will only accelerate the process of substituting U.S. products and technologies with homegrown inventions in China. Additionally, against a backdrop of an escalating U.S. crackdown on China’s science and technology, China would have to launch countermeasures instead of seeking further cooperation with the U.S.

The current U.S. policy framework of scientific and technological competition with China violates both the principle of innovation and the law of the market. It will neither benefit the U.S. nor truly succeed. Its implementation will only endanger the global scientific and technological system and hinder global innovation.

The author is an associate research fellow with the Chinese Academy of Science and Technology for Development.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +