The Human Side of Poverty Alleviation

Poverty alleviation is here to stay—not only is it sustainable, but it is imperative that it is sustained. It is cost-effective because the short-term economic costs are offset by a long-term growth in local, regional and ultimately national economy.

Poverty shouldn’t be a controversial subject, but it is. The World Bank, the World Health Organization, the U.S. State Department and pretty much every government in the world has a different definition of what poverty means. In China, absolute poverty is defined as 11 yuan a day; this is about $1.7. The World Bank disagrees and sets a higher number. In 2011 the U.S. considered people to be in poverty if their consumption was less than $21.7 a day. If that were the case, given inflation, almost all Chinese people outside of a few large cities would be in poverty. But living in China is different.

China doesn’t claim poverty eradication; it boasts a poverty alleviation program. The aim is to lift every Chinese person into a category they call moderately prosperous. So the idea of putting a monetary value on poverty has little meaning. Instead of a monetary amount, let’s consider the statement: “Where a person’s resources are insufficient to meet their daily needs,” and surely, most can agree this is a place we would not like to find ourselves in.

Since different governments, economists, journalists and academics all have different views on how to define poverty, China has simply made it policy to eliminate the “two worries” of hunger and clothing and fulfill the “three guarantees” of healthcare, housing and education. Based on these five categories, no one should need worry about their basic life needs. In 2015, Chinese President Xi Jinping challenged the government to go and find every family living in absolute poverty and lift them out of it—and they did. With minor exceptions being dealt with at the local level, they have achieved this goal.

Misunderstandings

However, in most Western mainstream media, we see a few kind words followed immediately by criticisms or even examples of an individual with a problem. When 800 million people are lifted from absolute poverty, it should be a cause for celebration, not criticism. In a statement given to the New York Times, Martin Raiser, the China Director of the World Bank said: “We’re pretty sure China’s eradication of absolute poverty in rural areas has been successful—given the resources mobilized, we are less sure it is sustainable or cost effective.” Raiser’s statement fails to take into account the culture and societal nature of China’s poverty alleviation program.

It will be sustainable because the government is committed to sustaining it; the Chinese people are on board with it; and they are supportive of the government in how it is being handled. For many reasons, there is a strong feeling of national pride inside China: economic growth, technology leaps, pollution control measures, the burgeoning strength of the military, the ability to help other countries, the handling of the epidemic, the Belt and Road Initiative, and particularly the poverty alleviation program.

China is resurgent, to a point where it feels it belongs. If outsiders, even those well-informed, believe poverty alleviation will slip backwards or is unsustainable, then they are not as well-informed as they may think. Sustaining the poverty alleviation program is a given.

Is it cost effective?

Only an accountant or an economist from a capitalist background would make such a statement. What is the human cost of lifting families out of poverty? Can that cost be measured by something as crass as money? Simply put: No, it can’t, or at least it shouldn’t be. It is this characteristic of the Chinese people that is so grossly underestimated. As with sustainability, China has a commitment to the people in rural areas, it is making positive changes and, because of the stable nature of politics in China, the programs will continue. They aren’t subject to the whims of politicians seeking election.

These changes will become self-sustaining or, if insurmountable difficulties are encountered, they will be amended or revised. They will not be abandoned due to financial costs because to do so would return families back to the life they left behind. To suggest it might not be sustained is to insult those involved, not only the Chinese Government who organize, direct and mostly fund it, but the Chinese people who live it. Poverty alleviation is not just a simple case of throwing money at a problem but a case by case program that considers sustainability and cost.

Seeing is believing

I first became aware of poverty alleviation reading reports in the Chinese media a few years ago and I was well aware there was an imperative need for it. Having lived in China for many years and being involved in charity fundraising since 2005, I was aware that there was a lot of poverty, even in the cities.

I have traveled a lot within China and passed through some of its most poverty-stricken places. In 2014, together with a friend, I cycled across China, from the southeast up to the northwest, through Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region and into Gansu Province and Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. It was an amazing experience in terms of scenery, the mountains and deserts, but we also encountered a different kind of poverty. The desert is not a friendly place, eking out a living is difficult and so Gansu, Ningxia and Xinjiang, which all contain deserts are very poor places. It was the first region I’d been to where I saw cave dwellers.

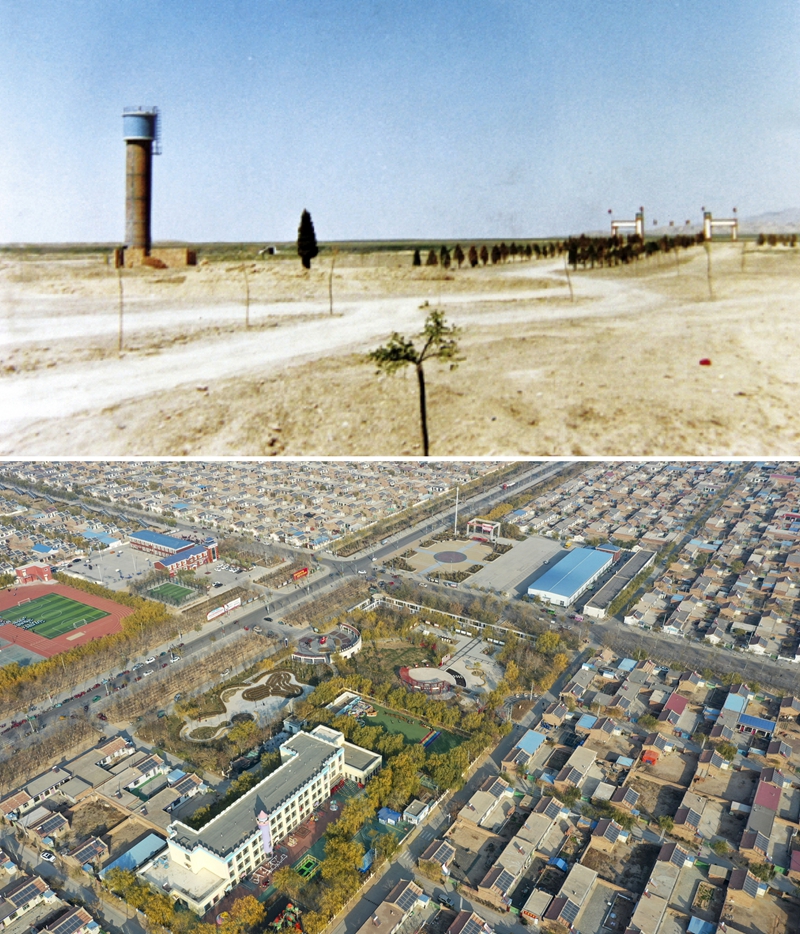

In 2019, I was traveling the same route, in a different direction and this time with my wife—I remember telling her of the abject poverty in Ningxia, the poor quality of the roads and the fact that many people still lived in adobe houses and the difficulty of finding decent hotels outside the main cities.

But what we saw was very different; the main roads were all well paved; the side roads to the villages were smooth concrete and in good repair; the hotels were better; and I found the place where people had been eking out an existence in poverty transformed. Instead of donkey carts, there were motorbikes; instead of huts there were high-rise blocks; there was even a cinema; and all these changed in just six and a half years.

China’s system is not a “throw money at the problem” solution. What we see is not one project, but thousands of targeted and bespoke initiatives which capitalize on local resources, both human and natural. We’re seeing a Party-driven program, incorporating industry, local governments, academics and grassroots guidance. It often uses local resources at the micro level to boost local economies and create jobs. The dovetailing of academia and industry into government plans, with telecommunications and infrastructure support are what makes these initiatives work.

Are there any negative sides?

There are without question many positive aspects to poverty alleviation. But it is not perfect. There are some social changes that have been underestimated; there are some minor failures in the system, mostly brought about by individual error or incompetence but generally quickly rectified and resolved. I have heard of some accounts of corruption in Western media, but I am convinced that if they were true, they would be immediately and harshly dealt with.

Poverty alleviation is here to stay—not only is it sustainable, but it is imperative that it is sustained. It is cost-effective because the short-term economic costs are offset by a long-term growth in local, regional and ultimately national economy.

Jerry Grey is a China watcher living in China who cycled across the country.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +