The Real History of Britain’s Relations with Hong Kong

Objectively, Hong Kong’s economy thrived fundamentally because of its links to China.

Editor’s Note:The recent events in Hong Kong and subsequent comments made by senior members of the British government have caused political tension between China and the United Kingdom.

The proposal of an Extradition Bill brought forward by Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam in February earlier this year, now suspended, had resulted in a number of protests in the region, the latest on Sunday 7 July.

In response to the protests, Britain’s Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt made a series of comments that have angered Beijing, involving himself in what China calls its own internal affairs

“We have good relations with China… there’s no reason why that can’t continue. But, for us, it is very important that the ‘one country, two systems’ approach is honoured.” Hunt said last week, also stating the government takes the situation ‘very, very seriously’.

In response, the Chinese government has issued a number of statements strongly rebuking Hunt’s comments, including from Beijing’s ministry of foreign affairs, who’s spokesperson Geng Shuang said Mr. Hunt appeared to be “basking in the faded glory of British colonialism and obsessed with lecturing others”.

On Sunday, China’s Ambassador to the UK Liu Xiaoming criticized Hunt again for his earlier comments, accusing the foreign secretary of adopting a “Cold War mentality”.

“We are strongly opposed to British intervention in Hong Kong’s internal affairs. We are still committed to this golden era between our two countries, but I cannot agree with some politicians’ description of the relationship, even the use of the so-called ‘strategic ambiguity’,” Liu said.

“This language does not belong to the vocabulary between China and the UK. It is Cold War mentality language.”

The following article by John Ross, Senior Fellow of Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China, was published on the twentieth anniversary of China’s resumption of the exercise of sovereignty over Hong Kong. It, however, provides a historical background to recent events in Hong Kong.

July 1st will be the 20th anniversary of the correction of one of the great crimes against China and the dirtiest episodes in Britain’s history. It will be the anniversary of the return of Hong Kong to China.

July 1st will be the 20th anniversary of the correction of one of the great crimes against China and the dirtiest episodes in Britain’s history. It will be the anniversary of the return of Hong Kong to China.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has strongly stressed that reunification with Hong Kong was a great victory achieved by China on the path of full national unity and that this victory was even greater because it was achieved by peaceful means. This article examines the huge problems created by Britain’s occupation of Hong Kong and therefore aims to help understand what an enormous achievement that the return of Hong Kong to China was and place in context how any remaining problems will be fully overcome.

Britain’s Damage to China

Britain’s occupation of Hong Kong began with hypocrisy, continued with hypocrisy, and some of Britain’s statements to this day continue to reek of the same hypocrisy. Britain’s actions did great damage not only to China’s Mainland but to the people of Hong Kong and to Britain itself. The most important people to celebrate national reunification on 1 July are therefore the Chinese people in both China’s Mainland and Hong Kong. But the British people also have their own smaller reason to participate in this celebration.

The damage to China from Britain’s actions on Hong Kong is well known. The seizure of Hong Kong and the Opium Wars opened up over a century of foreign aggression against China. It is estimated that one hundred million Chinese people died or martyred themselves as a direct and indirect result of these events, before the Communist Party of China (CPC) finally freed China from foreign intervention. Someone who is Chinese can explain infinitely more adequately than a foreigner the national pain and sacrifice of that struggle so I will not try. All I can say is that strangely it was a supporter of the Kuomintang who movingly summarised it on the anniversary of the creation of the PRC in a way non-Chinese could clearly understand: ‘Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai drove the foreign occupiers out of China and no one can take this glory away from them.’

Because someone who is Chinese can deal with the effects on China far more adequately than I can, here I will deal with the effects of Hong Kong on two other groups of people – on Britain and on Hong Kong. On the latter, I have perhaps one advantage that, because I am not Chinese, some people in Hong Kong speak to me more openly than they would someone from China’s Mainland. I hope making this analysis may make it easier to understand the origins of some issues with Hong Kong and how they will be historically overcome as the legacy of British colonialism fades.

Because someone who is Chinese can deal with the effects on China far more adequately than I can, here I will deal with the effects of Hong Kong on two other groups of people – on Britain and on Hong Kong. On the latter, I have perhaps one advantage that, because I am not Chinese, some people in Hong Kong speak to me more openly than they would someone from China’s Mainland. I hope making this analysis may make it easier to understand the origins of some issues with Hong Kong and how they will be historically overcome as the legacy of British colonialism fades.

Britain and ‘Western values’ in Hong Kong

Starting with Britain, how did it gain Hong Kong? It waged a war to force China to import opium – that is Britain condemned millions to misery and death by drug addiction so Britain could make a profit. This was hypocrisy of ‘Western civilization’.

Britain then continued to rule Hong Kong for over 150 years, for most of that time with a racist system of a British elite and a few hand-picked rich Chinese, without ever allowing the election of the governor of Hong Kong – only to suddenly discover when Hong Kong was to be returned to China it was a ‘fundamental principle’ Hong Kong must elect its governor by a specific system. It is strange that this ‘fundamental principle’ was never carried out by Britain. The consequences for Hong Kong of Britain’s deliberate attempt to create a Hong Kong ‘comprador elite’ cut off from and actively hostile to China are analysed below.

When Margaret Thatcher said Britain should continue to play some role in the running of Hong Kong after its return to China, she received a blunt ‘no’ from former Chinese Vice-Premier Deng Xiaoping. So shocked by his response, the ‘Iron Lady’ famously fell over at the shock of meeting a real great historical figure.

When Margaret Thatcher said Britain should continue to play some role in the running of Hong Kong after its return to China, she received a blunt ‘no’ from former Chinese Vice-Premier Deng Xiaoping. So shocked by his response, the ‘Iron Lady’ famously fell over at the shock of meeting a real great historical figure.

Now that Hong Kong has been returned to the country from which it was stolen by force and drugs, it incidentally does now chose its chief executive using a more democratic system than Britain ever allowed. People who facilitated the previous undemocratic system, such as the last governor Lord Patten, continue to write hypocritical articles which never explain the real history of Britain’s involvement in Hong Kong.

There is a lesson in all this for Britain itself. Marx famously wrote ‘A nation that enslaves another forges its own chains’. He said it about Britain’s relation to Ireland but it equally applies to Hong Kong. Among the chains that a country forges for itself by enslaving another are mental ones. Britain cannot see its own reality until it sees honestly the hypocrisy and crimes its colonialism inflicted on other countries. Discovering the truth about Britain’s past, including centrally on Hong Kong, is therefore part of the road to Britain’s own real liberation.

In Britain’s foreign relations there is a simple test to find out what Britain should be proud of and what it should be ashamed of and Hong Kong forms a central part of that. Numerous things from Britain are avidly voluntarily welcomed by other countries – Shakespeare, Newton, Darwin to Harry Potter! These are things every person in Britain can and should be proud of. Those things which Britain enforced on other peoples and countries by force – the Atlantic Slave trade, the occupation of Ireland, the occupation of India, and centrally the occupation of Hong Kong – are things to be ashamed of in Britain’s history.

So, on 1 July people in Britain should join China’s great celebration and have a glass of champagne or baijiu (a strong Chinese liquor) to celebrate the anniversary of the righting of a great wrong – the seizure of Hong Kong. And by sweeping away the cobwebs of Britain’s hypocrisy on Hong Kong this will not only celebrate China righting a great wrong but help to create the mental conditions for really liberating Britain itself from the same hypocrisy and chains.

Britain’s Effect on Hong Kong

Turning to Hong Kong, the way I am viewed by people in Hong Kong who do not know me is inevitably different to someone from China’s Mainland – because I am not Chinese and because my country Britain was the former colonial power. Therefore, initially, some people speak to me more ‘openly’ than they would to someone from China’s Mainland. As I therefore have experiences not directly available to people from China’s Mainland, it may be useful to give some of these. I apologise in advance some of this information may appear ‘offensive’ but it is only useful in such an important matter to present the real situation. They may help explain some problems in Hong Kong which flow from the legacy of British rule.

Britain ruled the largest Empire in history. Its own forces were tiny compared to the territories it ruled, therefore, it could not only rely on armed force. It had to find a way to divide the populations it ruled and create layers who betrayed their own country and supported Britain. Britain had two standard techniques for this. First, to create a ‘comprador elite’ – that is a small privileged group of the country it ruled who were allowed to become rich under British rule and were given some access, even if second class, to high British society. Second to create a ‘slave mentality’, that is worship of the British rule, among some somewhat wider layers, often by getting such layers to look down on and despise others in the population. Both techniques were used in Hong Kong.

To make a comparison, if in India Maharajas were allowed to keep local powers, parade with elephants in front of Queen Victoria or her emissaries, and join British cricket clubs, then in Hong Kong the local and appointed British rulers, who were few in number, allowed some locals to become rich and also join exclusive British clubs.

To make a comparison, if in India Maharajas were allowed to keep local powers, parade with elephants in front of Queen Victoria or her emissaries, and join British cricket clubs, then in Hong Kong the local and appointed British rulers, who were few in number, allowed some locals to become rich and also join exclusive British clubs.

To take another comparison, in Ireland, Protestants were encouraged to look down on the majority Catholic population: in Hong Kong some local social layers were encouraged to see themselves as superior to people from China’s Mainland. Britain engaged a similar strategy in the south of the United States. In the U.S., southern states where the ‘poor whites’ who lived in poverty and were exploited by their local rulers, but they were also encouraged not to challenge this by ‘looking down’ on the black population. In Hong Kong, the British encouraged parts of the local population to ignore the fact they were excluded from all real power in Hong Kong by considering themselves superior to China’s Mainland. There were, of course, always strong Chinese patriots in Hong Kong but Britain did everything it could to ‘divide and rule’. This explains some of the key problems faced during and after Hong Kong’s return to China.

Objectively, Hong Kong’s economy thrived fundamentally because of its links to China. Indeed, there is an obvious ‘win-win’ for both China’s Mainland and the special administrative region. As long as China does not have a fully liberalised capital account, which cannot be done too quickly, it needs an offshore base to carry out Renminbi and other financial operations. Hong Kong is ideal for this. As China develops even more internationally, with initiatives such as The Belt and Road Initiative and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Hong Kong can play a key role in this international expansion. But parts of the Hong Kong business elite for many years were integrated into the structure of their British rulers and are encouraged by the West not to orient to China’s economic needs. China’s economic success will overcome these problems but they create some temporary frictions.

This economic reality interacts with politics. Britain never allowed elected governors in any form during its 150 years occupation of Hong Kong. But some in Britain suddenly announced the direct election of the Hong Kong Executive as a ‘fundamental principle’ after Britain left Hong Kong. One aim in this was to encourage separatism – groups in Hong Kong were transparently financed and aided from abroad and acting in an organised way with Taiwan separatists who were similarly aided and financed from abroad.

This economic reality interacts with politics. Britain never allowed elected governors in any form during its 150 years occupation of Hong Kong. But some in Britain suddenly announced the direct election of the Hong Kong Executive as a ‘fundamental principle’ after Britain left Hong Kong. One aim in this was to encourage separatism – groups in Hong Kong were transparently financed and aided from abroad and acting in an organised way with Taiwan separatists who were similarly aided and financed from abroad.

This interacted with some parts of the Hong Kong population who were encouraged by the British to have a ‘poor white’ attitude to China’s Mainland citizens. Here I apologise for telling true stories which are deeply offensive but they show the depth of the problem created by British rule.

At its most extreme, one person from Hong Kong I knew who was based in Britain insisted on cleaning the plates when visiting a restaurant in China’s Mainland because they didn’t believe the locals could wash them properly – naturally when I found this out I ended all relations with them. I know from writing about it on Chinese social media site Weibo, that Chinese working in Hong Kong found they were discriminated against by some local Hong Kong colleagues – because their Hong Kong colleagues had been educated by the British to consider themselves superior to Mainland Chinese.

But the same people in Hong Kong who considered themselves superior to their countrymen and women from China’s Mainland were servile to those from the West.

Such attitudes by some Hong Kong people created by British rule, as is well known, even damaged Hong Kong’s economy by harming tourism from China’s Mainland.

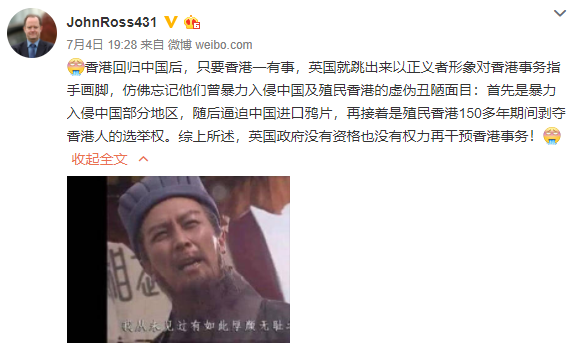

A Weibo post I wrote on Hong Kong and British hypocrisy became the number one ranked post in China, and was even written about in U.S. foreign policy magazines, so I know my analyses on this does not represent a fringe opinion.

I have no doubt from my experience that these problems will be overcome. There are real Chinese patriots from Hong Kong who I have also met. China’s economic success is so great it provides the real centre of gravity for Hong Kong’s economy. I know people from Hong Kong were repelled by the damage the 2014 Occupy Movement protests did to its economy and the CPC has taken the right choices on all major issues regarding Hong Kong.

I have no doubt from my experience that these problems will be overcome. There are real Chinese patriots from Hong Kong who I have also met. China’s economic success is so great it provides the real centre of gravity for Hong Kong’s economy. I know people from Hong Kong were repelled by the damage the 2014 Occupy Movement protests did to its economy and the CPC has taken the right choices on all major issues regarding Hong Kong.

Chinese national identity is finally strong enough to overcome any of these problems I mentioned in Hong Kong. But the legacies of British colonial rule and intervention in China which started with the seizure of Hong Kong did enormous damage not only to China but to Hong Kong and to Britain – as this article has analyzed.

Editor: Thomas Scott-Bell, Dong Lingyi

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +