Time Will Tell if Trump’s Iran Strategy Proves Effective After Saudi Arabia Attack

Even as Iran demands the U.S. to honor the JCPOA, it is steadily downgrading its commitments. In May it warned European Union members that it would restart parts of its nuclear program to put pressure on them to respond.

A drone-led attack on Saudi Arabia’s main oil processing plant at Abqaiq on Sept. 14 cut the country’s production by half and the global supply by 5%. In the immediate aftermath, oil prices surged 20% as well. At first, the Houthis, a Yemen-based rebel group aligned with Iran, claimed responsibility. But the Saudis and the U.S. believe that Iran was behind the attack, leading to commentators and analysts watching closely to see what they would do.

Rather than immediate military response, U.S. President Donald Trump said he was looking at “many options” on how to deal with Iran. Among them include a proposal to increase economic sanctions against Iran. Another was to wait and see what United Nations investigators discover at the site as well as what the Saudis propose. To show they mean business, the U.S. also dispatched troops to the Gulf, presumably to provide vanguard for any military action but also to help support Saudi Arabia’s air defenses which failed to stop the drone attack.

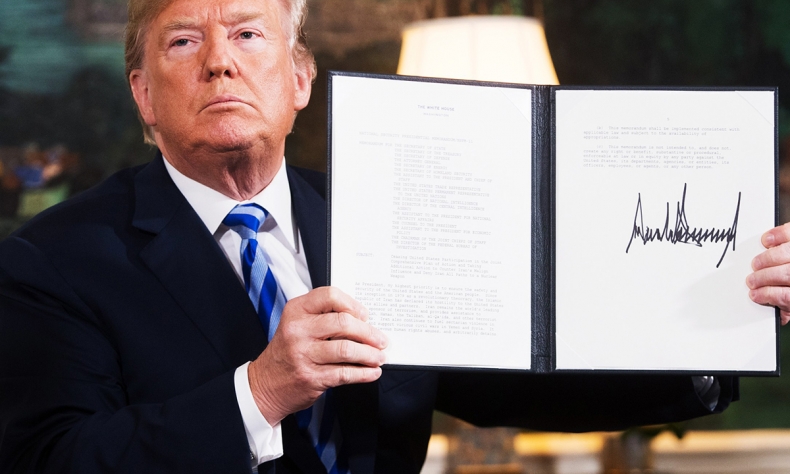

But questions will be asked concerning American effectiveness as well as Saudis’ lack of preparedness. Over the past year, the U.S. has applied its “maximum pressure” strategy to contain Iran and bring it to the negotiating table. The strategy has its roots in Trump’s antipathy towards the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), a deal which was signed between the five permanent UN Security Council members (Russia, China, France, Britain and the U.S.) and Germany with Iran in 2015. Iran agreed to freeze its nuclear deal in exchange for having sanctions lifted. But U.S. allies like Saudi Arabia and the UAE were unhappy seeing their Iranian rival brought in from the cold while Trump promised to replace the “bad deal” with a better one while on the campaign trail in 2016.

After withdrawing from the JCPOA, the U.S. re-imposed sanctions against Iran and threatened any country which continued to trade with it. Fearing the worst, various countries stopped buying Iranian oil which squeezed the economy. But crucially, the U.S. was unable to undermine the consensus over the JCPOA and get the other signatories to abandon it.

Trump also didn’t count on Iran pushing back. Its leaders started acting in a disruptive manner. Tehran was alleged to have orchestrated several attacks against shipping vessels and detained two British tankers in the Gulf during the summer. Meanwhile, their Houthi allies provided early signs of the Saudis’ aerial vulnerability when they carried out a drone attack against a pipeline deep inside the country.

Overall, the Iranian strategy has been successful by acting in ways that provide it with a cloak of deniability. It has also avoided civilian casualties, both in Abqaiq as well as when they shot down an American drone in June. This has made it harder for the U.S. and its allies to justify a military attack in retaliation. Indeed, Trump claimed that he pulled back from ordering an airstrike in response to the June incident when he learned how many would die as a result.

The U.S. approach hasn’t helped by an apparent lack of consistency. Trump’s rhetoric has oscillated between confrontation and conciliation – even offering to meet with Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani. The American president prides himself as being an effective deal-maker. But he may be overestimating his power of persuasion. His three meetings with Kim Jong-un have failed to curb the DPRK’s nuclear program.

Even as Trump built up the American military presence last week, his preference is to talk with the Iranians rather than fight them. He was elected in part because of his opposition to America’s military involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan. And even though he has shown a propensity for former generals to serve in his cabinet, his inclinations are dovish. In mid-September, the administration’s war-hawk, John Bolton, was dismissed as National Security Adviser, following repeated differences of opinion with Trump during his eighteen months in office.

The problem for Trump is that Iran is not willing to give him what he wants. For one, even though Iran’s economy is struggling, its political leaders remain defiant. The country’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has ruled out any prospect of a Trump-Rouhani summit during the UN General Assembly. In addition, Trump may well find that even if he could achieve a meeting with Rouhani, his objective is effectively a non-starter.

For now, Trump’s and Iran’s positions are too far apart for a new deal. For Trump, the JCPOA was too limited and did not deal with Iran’s influence in countries like Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Gaza and Yemen. Like its Gulf Arab allies, it wants to see any new settlement deal with Iran’s wider role in the Middle East. By contrast, for Iranian leaders, an agreement already exists in the form of the JCPOA. Consequently, they demand that the U.S. return to its provisions.

Even as Iran demands the U.S. to honor the JCPOA, it is steadily downgrading its commitments. In May it warned European Union members that it would restart parts of its nuclear program to put pressure on them to respond. That has so far resulted in the EU creating INSTEX, a mechanism to enable firms to trade in Iran without falling foul of American sanctions. More recently, France’s President Emmanuel Macron has also proposed establishing a credit line worth $15 billion. Despite these efforts, Iran began to increase its stockpile of nuclear material.

Given the current circumstances, if Trump is unwilling to adopt a more hardline and military response against Iran, he might think that a return to the JCPOA as a pre-condition for further talks might be worthwhile. Presumably, the EU could be counted on to present the same message as well. But if he did so, the real winner would likely be Iran, since it would herald a return to the deal without having to accept Trump’s wider goals.

Guy Burton is a Visiting Fellow at the LSE Middle East Centre and an Adjunct Professor in International Relations at Vesalius College in Brussels.

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors only, not necessarily those of China Focus.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +