Warriors on Wings

In an era when Chinese-American relations face challenges, an organization is promoting the shared ‘Flying Tigers’ legacy as a reminder of what can be achieved with solidarity.

In 2023, Chinese President Xi Jinping received an unusual letter. It was from an American, Jeffrey Greene, chairman of an organization called the Sino-American Aviation Heritage Foundation. It said the foundation was planning to bring two “Flying Tigers” and several “Flying Tiger” family members to China, and the group was looking forward to the visit.

About 10 days later, Greene received a call from the office of the Chinese Ambassador to the U.S., saying President Xi had replied to the letter. He recalled his excitement on receiving the president’s reply. “[President Xi] recognized the work our foundation has done over the years in bringing Flying Tigers veterans back to visit China,” Greene told China Today. “He did not stop there… he emphasized the importance of bringing our students … to China so that young people can be educated and so we can have ‘Flying Tigers’ in the future. Xi said, ‘I hope that the spirit of Flying Tigers will be carried on from generation to generation among Chinese and American peoples.’”

Who were the Flying Tigers?

During World War II, there was a growing voice in the U.S. that the U.S. should do something to help China stop the Japanese aggression. A group of American military pilots volunteered to defend China. The man behind this was Claire L. Chennault, a retired U.S. Army Air Corps captain who was serving as a key advisor to the Chinese Air Force.

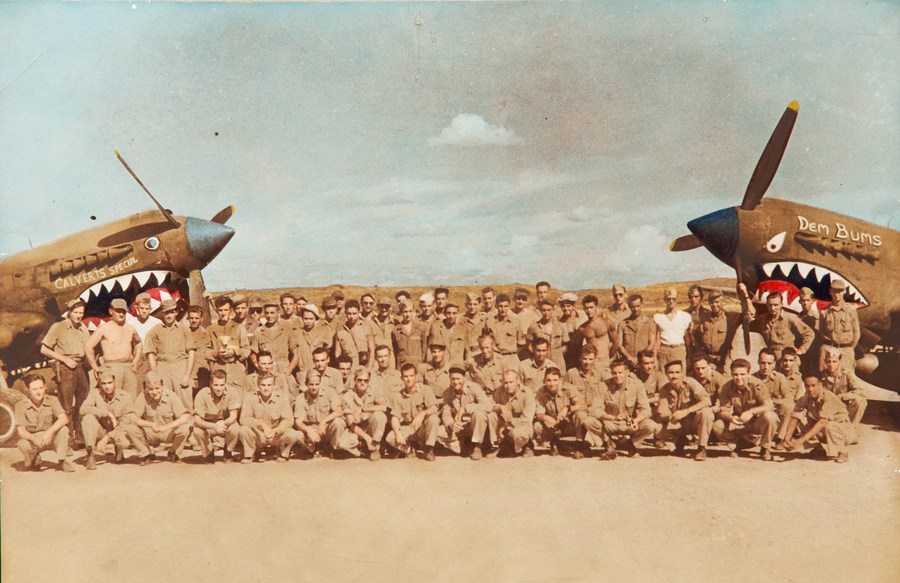

During the winter of 1940–1941, Chennault supervised the purchase of 100 Curtiss P-40 fighters and the recruiting of 100 pilots from the U.S. Army Air Corps, Navy, and Marine Corps, and over 200 ground crew and administrative personnel. The group was first called the American Volunteer Group (AVG) of the Chinese Air Force.

Then they became famous as the “Flying Tigers.” According to Greene, this moniker was given after people saw them successfully shoot down Japanese planes in the Chinese skies. “The mythical flying tigers in Chinese culture are immortal and cannot be defeated,” Greene said.

Their mission began with the assignment to protect the Burma Road that connected Lashio in Burma in the south to Kunming in China in the north. It was a vital artery via which allies were sending supplies to Chinese forces from Rangoon in Burma, now called Yangon.

The first exchange of fire with Japanese bombers occurred on December 20, 1941. Greene said during that exchange the 1st and 2nd Squadron of the Flying Tigers intercepted 10 unescorted light Ki-48 “Lilly” bombers that were about to attack Kunming. They surprised the Japanese and shot down three bombers near Kunming and one more crashed before making its way back to their base in Hanoi, Vietnam.

Later Chinese intelligence intercepted Japanese communication saying that only one or two of their 10 bombers returned to the base and all had dead or wounded crewmen. As a result, it would be a year and half till the Japanese would try to bomb Kunming again.

The AVG was disbanded in 1942 and many of the surviving pilots returned to their original military services. Their success was largely the result of fine-tuned unorthodox dive and zoom tactics. Chennault also set up a warning system network of people at airfields and strategic locations around unoccupied China who would notify the Flying Tigers when they saw Japanese aircraft flying overhead, especially in the unoccupied western region of China.

Later the Flying Tiger legacy was carried on by the 23rd Fighter Group China Air Task Force, which flew A-10s with shark’s teeth markings in combat missions in Afghanistan, as well as the Chinese-American Composite Wing (CACW), a combined United States Army Air Forces and Republic of China Air Force unit, till August 1, 1945. The CACW’s aircraft, manned by American and Chinese pilots and air crew, also adopted the AVG’s famed nickname Flying Tigers.

Keeping the legacy alive

Greene described the bond, camaraderie and solidarity of the Flying Tigers. While U.S. pilots volunteered to help the Chinese fight the Japanese troops, just as amazing was the bravery and sacrifice of countless Chinese, from peasants to guerrilla forces. They helped the pilots who were shot down or landed in Japanese-occupied regions of China to escape to safety despite the brutal Japanese retaliation. Due to this, most of the Flying Tiger pilots who survived emergency or crash landings made it back to their units.

In 1998, along with veteran Flying Tigers, Greene set up the Sino-American Aviation Heritage Foundation to rekindle the spirit of cooperation between China and the United States by celebrating the contributions each has made, together and separately, to aerospace technology, science, commerce, and exploration.

The foundation’s work is multi-faceted. Over almost 30 years, it has brought nearly 500 Flying Tiger veterans back to visit China, along with their families and descendants. “As they visited the different places (where) the Flying Tigers fought during the war, the veterans were greatly impressed with how China has changed since the war, and took satisfaction that they had a part in helping build what became modern China,” Greene said.

The foundation has also taken part in dialogues between Chinese and American astronauts. In 2005, former NASA administrator Major Gen. Charles Bolden, former American astronaut Brigadier Gen. Charles Duke, and Mae Jemison, the first African-American woman to travel into space, came to China to meet Yang Liwei, China’s first astronaut to travel into space, on an official visit sponsored by the Chinese government. It was an inspiring moment when China’s first astronaut in space shook hands with his American counterparts.

The foundation has also held photo exhibitions in China and the U.S. to tell young people about the history of the Sino-American friendship through the story of the Flying Tigers. The first exhibition was held at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., the second at the National Museum of the United States Air Force. In 2024, photo exhibitions were held at the Anti-Japanese Aviation Martyrs Memorial Hall in Nanjing, and in other Chinese cities such as Changsha and Urumqi.

Expanding in education

In 2022, the foundation expanded its work in education with the Flying Tigers Friendship Schools and Youth Leadership Programs. The friendship schools program sets up cooperation friendships between schools in China and the U.S. The vision is to strengthen communication and exchanges, enhance mutual understanding, and work together to meet global challenges. By 2024, this program covered over 20 schools in the U.S. and over 60 in China.

Last year, the foundation brought a group of 70 students from middle and high schools and universities from 11 states in the U.S. to take part in the Chinese Bridge Flying Tigers Summer Camp for American students. It was the first event of its kind.

During the visit, the students were taken to key areas where the Flying Tigers had been based and also to Chinese schools.

“It was a really nice experience bonding with these young kids and showing them a little bit of the American culture and seeing their Chinese culture. We’ve benefited a lot from them,” said Synthia Alexa Gonzalez, a student from the International Leadership of Texas, a free public charter school in Texas, who took part in the Chinese Bridge Flying Tigers Summer Camp.

Jorge Luis Valdez, a teacher from the same school, shared his insight: “There are a lot of similarities between America and China on how we show our respect for our fallen heroes, the ones who pay the ultimate sacrifice for us to continue living in our countries.”

This year, the foundation will bring 100 descendants of the Flying Tigers to China to take part in the 80th anniversary celebrations of the conclusion of WWII. It also plans to bring more students to China in cooperation with different Chinese organizations and to take Chinese students to the U.S. to meet the descendants of the Flying Tigers and visit a number of the programs schools.

Greene says they are trying to promote the “opening up of a road of communication that never should have closed. Sharing the wartime legacy of the two great countries by taking young people to visit historic airfields, battlefields, and museums – seeing how Chinese people view Flying Tigers – they will be able to make up their own minds about China and then tell their families and friends what they have seen and heard.”

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +