When Not to Party: The Weakness of British Democracy

If national leaders are to be virtuous, this must surely be true of leading nations; there is no virtue in breaking international law.

In 2020 and 2021, the British prime minister attended multiple social gatherings that were prohibited due to the Covid-19 pandemic. According to the official “Gray Report”, published on May 25, 2022, they “should not have been allowed to happen.” Dubbed “Partygate”, this is not just a storm in a British teacup.

Nor is it merely symptomatic of the intellectual corruption currently eroding British democracy. Instead, it potentially undermines the legitimacy of the global world order and has profound implications for Sino-British relations.

The context is important. An inquiry conducted by two parliamentary committees has concluded that “decisions on lockdowns and social distancing during the early weeks of the [Covid-19] pandemic—and the advice that led to them—rank as one of the most important public health failures the United Kingdom has ever experienced.” The initial assessment was that, without vaccines, it was “not possible to stop everybody getting” Covid-19 and that “some immunity in the population” was needed. This led to “fatalism” and to a policy “effectively relying” on the development of “herd immunity”. The government, therefore, sought to manage rather than to suppress infection.

The inquiry criticises the government for its “unwillingness to consider seriously and act on the approach being taken in [China’s] Taiwan, Singapore or Korea”, namely one of lock-down and tracing. The explanation given by Dominic Cummings, former chief aide to the prime minister, hints at prejudice: “the British public would not accept a lockdown [or] what was thought of as an east Asian-style track and trace-type system and the infringements of liberty around that”. In similar vein, China’s policy of containment was never considered. Indeed, Dr Richard Horton, editor of the prestigious medical journal, The Lancet, is very critical that three articles published in January 2020 analyzing the situation in China were overlooked. This meant that the UK failed to use the time it had to prepare a strategy based on “testing, isolation, quarantine, physical distancing, and so on”. To date, Britain, with a population of 67.2 million has recorded 22.3 million cases of Covid-19 with 177,000 related deaths.

Some have suggested that the British prime minister did not take the pandemic seriously until he tested positive on March 27, 2020, and was hospitalized in intensive care. Certainly, he missed five consecutive meetings of the Civil Contingencies Committee – the body charged with managing the response to the pandemic – ostensibly, according to The Times, to write a book needed to fund his divorce. However, the realisation that the herd immunity policy was fatally flawed began to be recognised around March 13, a national lockdown was announced on March 23 and legally came into force on March 26, the day before the prime minister announced his positive test.

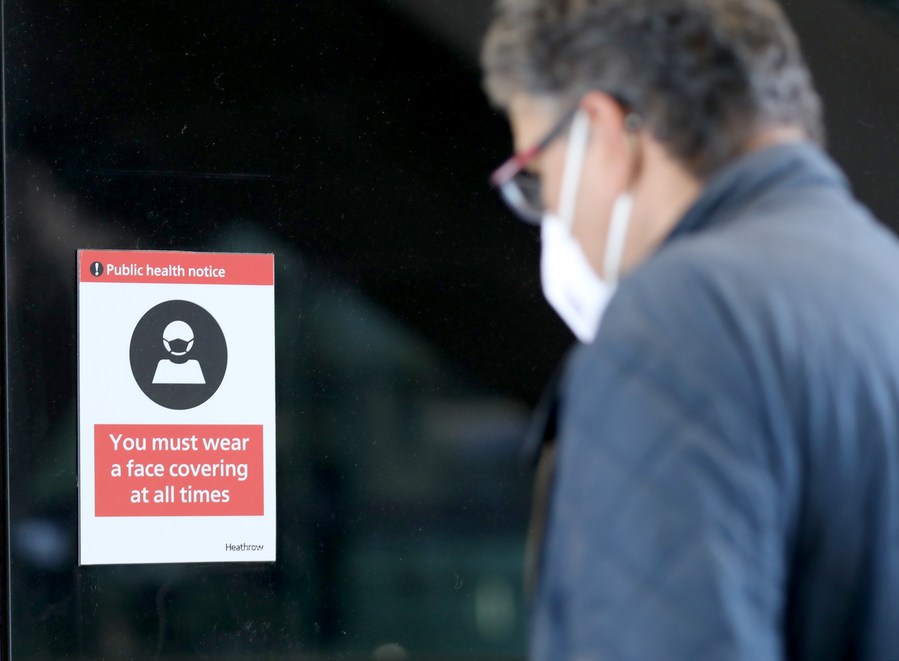

People unable to work from home were allowed back to work on May 10, 2020 and the phased reopening of schools began on June 1. However, local lockdowns were announced on July 4, a second national lockdown was imposed between November 5 and December 2, and a third from January 6 to March 29, 2021. Social distancing was not fully removed until July 19, 2021 and restrictions were again imposed on December 8, 2021 following identification of the Omicron strain.

The BBC list 14 events held at the prime minister’s residence, 10 Downing Street, between May 15, 2020 and April 16, 2021 that were prohibited under the social distancing protocol. These are the “Partygate” events that took place when ordinary citizens were forbidden even to be present at the death of loved ones. The Prime Minister has received just one fixed-penalty notice from the police for breaching Covid-19 laws. Even so, this makes him the only sitting British Prime Minister ever found to have broken the law.

These were not the first Covid-19-related events that implied one rule for the privileged elite and another for the population at large. According to Durham police, the aforementioned Dominic Cummings, the Prime Minister’s closest adviser, breached regulations by visiting a beauty spot 260 miles from home on April 28, 2020.

Why is this more than a storm in a teacup? Because on seven separate occasions the Prime Minister insisted to Parliament that all Covid-19 guidelines had been followed at 10 Downing Street. According to Erskine May, the British parliament’s rulebook, to deliberately mislead parliament is to be in contempt. While a cause for resignation, the Prime Minister has not resigned. Instead, he insisted that all Tory members of parliament vote against a proposition to hold an inquiry to investigate whether he had deliberately misled parliament. Those with integrity refused and an investigation has commenced. However, the prime ministers’ Cabinet colleagues argue that a resignation could “destabilise the government” at a time when it needs to be united against Russia.

Of course, times of international crisis require leaders with integrity who tell the truth. In 2004, the prime minister was sacked from his post as Shadow Secretary for the Arts for lying about an extramarital affair and a consequent abortion. He led the campaign for Britain to leave the European Union (Brexit) with statistics so blatantly false that, in 2016, the UK Statistics Authority issued a rebuke. In 2018, he was still repeating the same falsehoods. The prime minister is even accused of misleading the Queen over the proroguing of parliament in 2019. The prorogation was deemed to have been illegal by the UK Supreme Court and undertaken to silence parliamentary opposition to the Brexit strategy. Ironically, research published in 2021 reveals that British voters, journalists and parliamentarians all attach “the highest absolute importance to integrity in their politicians”.

Contempt for truth undermines democracy, denies the possibility of reasoned debate, and breeds distain for its institutions. There is concern that the British police have become politicised. Asked many times to investigate “Partygate”, they only did so when the critical Gray Report on the affair was about to be published. The report then had to be withheld pending the police investigation allowing pressure for the prime minister to resign to subside. Then again, while the police initially dismissed allegations of a breach of the Covid-19 regulations by the leader of the opposition Labour Party, the case was reopened immediately after the May 2022 local elections in which the opposition took council seats from the prime minister’s ruling Conservative Party. The leader of the opposition has promised to resign if he is issued with a penalty. This leaves the police as arbiters of the leadership of political parties in Britain. The police have also been asked to explain why penalties were issued to people attending events at which the Prime Minister was present but not penalised.

Dishonesty also destabilises international relations. In 2020, the prime minister presented legislation to parliament to unilaterally rewrite part of the Brexit withdrawal treaty with the European Union. He did so with the knowledge that doing so would break international law as well as reneging on an international agreement that he had negotiated. Less than two years later, the process is about to be repeated with ministers saying that they are “super cool with the idea of legislation to tear up the Northern Ireland Protocol unilaterally – despite the risk it could spark a trade war with the EU”.

Very recently, the British prime minister signed agreements with Finland and Sweden agreeing to come to their aid should either nation be attacked. Based on Britain’s recent contempt for international treaties, it would seem unwise for the Nordic nations to take these agreements at face value. Aid may be forthcoming conditional on it being in the domestic political interest of the British prime minister.

For the same reason, it is now hard to justify Britain’s privileged position as a permanent member of the UN Security Council. If national leaders are to be virtuous, this must surely be true of leading nations; there is no virtue in breaking international law.

Similarly, with faith in the truthfulness of Britain’s current leadership eroded, it is difficult to see Britain’s involvement with the United States and Australia in AUKUS as being to support its “security and defence interests”. Brian Harding of the U.S. Institute of Peace explains that “competing with China is at the centre of the Biden administration’s national security policy and increasingly an organising principle for the U.S.-Australia alliance”.

While Britain tilting its trade policy towards the economically dynamic Indo-Pacific region is understandable, claiming defence as the reason for sharing nuclear technology with Australia seems far-fetched. Maybe the British prime minister desperately needs a trade agreement with America to legitimate the Brexit strategy that he chose in order to become prime minister.

The article reflects the author’s opinions, and not necessarily the views of China Focus.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +