Who Is the Real Expansionist?

Since the end of the Cold War in 1991, each subsequent U.S. administration has emphasized that it is ‘on the right side of history,’ despite their expansionist attempts with catastrophic results, such as in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and Libya. From these instances, it is obvious who the real expansionist is.

During his May tour of the Republic of Korea (ROK) and Japan, mixing up security and trade, U.S. President Joe Biden made some announcements based on an assumption. So is his administration’s criticism of Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s recent visit to eight Pacific island countries. The assumption is that China is a growing expansionist threat to the region, the United States, and the West as a whole. But is that true? Does China aim to replace the U.S. as the global hegemon, remake the liberal international order, and threaten freedom and democracy everywhere, as Washington insists?

This assertion by various U.S. strategists is an alarmist vision that ignores the normal dimensions of regional cooperation. It also ignores the fact that other countries do not see China through Biden’s zero-sum-game eyes.

Regional cooperation vs. geopolitical confrontation

In ROK and Japan, Biden presented his Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), an initiative supposedly for greater economic engagement of the United States in Asia with 12 partner countries. However, the IPEF has also incurred suspicion and criticism from the countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). As the Bangkok Post put it: “Most capitals are keen to maintain amicable ties with China, balancing relations between Beijing, Washington, Canberra, and Wellington, while focusing on the more urgent threat of climate change and day-to-day economic issues.”

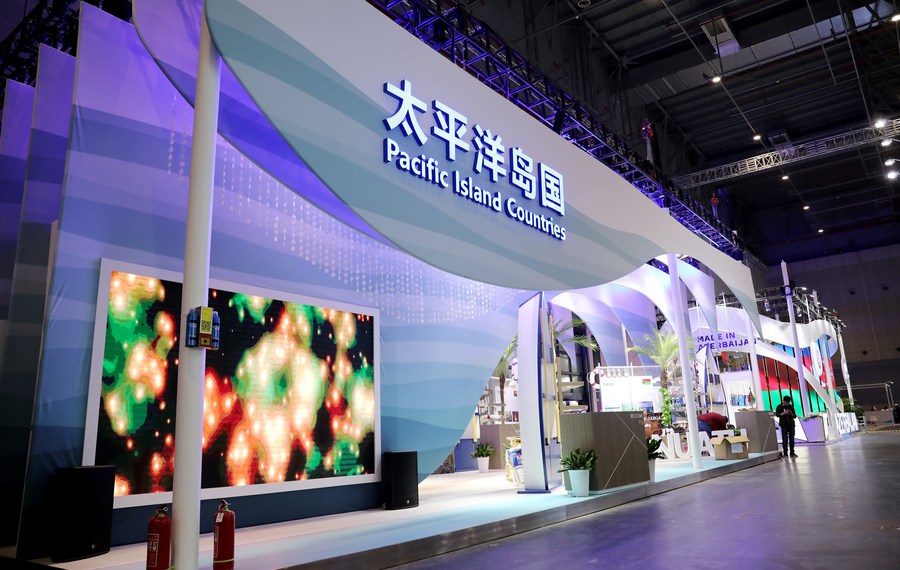

Beijing has shown its strong commitment to cooperating with other Asian countries on these pressing issues. This was reflected in the document “China’s Position Paper on Mutual Respect and Common Development with Pacific Island Countries” issued during Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit.

Wang Yi’s visit from May 26 to June 4 encompassed the Solomon Islands, Kiribati, Samoa, Fiji, Tonga, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, and Timor-Leste. In addition, he also paid a virtual visit to the Federated States of Micronesia. The issues discussed ranged from trade, fisheries, and infrastructure to climate change and security. He also held video conferences with the prime minister and foreign minister of the Cook Islands and the prime minister and foreign minister of Niue, and hosted the second China-Pacific Island Countries Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Fiji. In other words, this was a tour touching on a wide range of issues typical of modern diplomacy.

Biden’s Asia visit, on the other hand, smacked of military motives. He intended to broaden the focus of the U.S. alliance with Seoul and bring it closer to the QUAD, the strategic security dialogue between Australia, Japan, India, and the United States, thus trying to lead Seoul to join a policy of confrontation with Beijing. The visit also wanted to probe the possibility of a Japanese incorporation into AUKUS, the security pact that brings together Australia, the United Kingdom, and the U.S.

A juggling act

Biden’s visit has been seen in Asia as a strategic juggling game, viewed with much skepticism, particularly since Northeast Asia and ASEAN are aware of the erratic U.S. diplomatic policy over the last decade.

During his presidency, Barack Obama raised his Pivot to Asia policy, a misleading phrase because Washington has been anchored in Asia since World War II. Subsequently, he proposed the economic pact, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which was denounced by his successor Donald Trump. The U.S. president in turn converted it into the so-called Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy that was further redesigned by Biden into the current IPEF. Whatever the formula, the issue of credibility remains.

The evolution of AUKUS is another example. The United States and Great Britain’s interference still echoes in Asia, the latest instance being the catastrophic end of mission in Afghanistan last year.

The alarmist views about Wang Yi’s tour of Pacific island countries were responded by the Foreign Minister of New Zealand, Nanaia Mahuta, who said her country would remain essentially unchanged from those she had outlined for the Pacific relationship in November 2021 – building economic resilience, recovering from the pandemic, and responding to the climate crisis. In other words, goals coinciding with China’s position paper.

In addition, several Asian nations see potential threats posed by the probability of Trump returning to office in 2024, and the possibility of a Republican victory in the mid-term elections in November, which would see Biden’s promises in Asia-Pacific in tatters. While countries in Asia do not oppose U.S. economic engagement in the region, they strive against the strategy to force them to choose between Washington and Beijing. The Pacific nations are more concerned about recovery from the pandemic, conscious that they belong to a larger group of Asian nations. Additionally, they feel exposed to extreme weather events, a matter of urgent concern.

Washington argues that Beijing will eventually “invade” Taiwan to justify the presence of Western warships in the South China Sea and in Southeast Asia. It assumes that China is willing to discontinue cargo transit through these fundamental maritime areas of world trade, when such disruptions go against China’s own interests. The Taiwan “invasion” pretext is nothing but fiction since most countries in the world, the U.S. included, recognize Taiwan as an inalienable part of China.

Echoing a past injustice

It is true that a great power can wield transformation capacities even in the most distant continents. However, it is peculiar that before integrating important states into the U.S., for example Alaska and Hawaii, America went far from its territory to drive unequal treaties in Asia, forcing the Qing government to sign the Treaty of Wangxia in 1844. The treaty allowed America not only unequal trade advantages and the enjoyment of extraterritorial status, but also forced China to accept the expansion of American protestant missions.

In 2022, in order to maintain its dominant position in Asia-Pacific, Washington intends to exclude China, the largest economy in Asia, from the IPEF when it is already interlinked with the rest of Asia through a series of bilateral and multilateral economic pacts, including the world’s largest trade deal, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. China is also a world leader in renewable energy, including climate-friendly technologies, which are key to the survival of the planet, in addition to manufacturing and human resources.

Since the end of the Cold War in 1991, each subsequent U.S. administration has emphasized that it is “on the right side of history,” despite their expansionist attempts with catastrophic results, such as in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and Libya. From these instances, it is obvious who the real expansionist is.

The author is director of the Dialogue with China Project, an independent electronic platform.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +